The 102 starters of the Grand to Grand Ultra at the Stage 1 start line on the north rim of the Grand Canyon, Sunday, September 22. I’m somewhere in the middle. All photos in this post courtesy Grand to Grand Ultra, except for the personal shots toward the end.

I lay in my sleeping bag in the predawn hours of Friday, September 27, shivering while my stomach growled audibly and my abdomen muscles clenched. Cold seeped in through the bag’s ultralight layer and through my wool base layers and puffy down jacket. A rock, which was lodged in the hard earth under the tent’s ground cover, poked at my ribs because my minimalist sleeping pad had sprung a leak and deflated.

I was coping with insomnia in a brier-filled, ant-infested pasture somewhere outside of Kanab, Utah. During the day, we could see the coral and chalky-colored bluffs of Zion and Bryce national parks in the distance, so I knew I was getting close to reaching a finish line near Bryce’s towering hoodoos, overlooking the magnificent layer-caked landscape of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Three men and three other women slept beside me in this square white canvas tent. We had shared the past five days and 136 miles as competitors in the Grand to Grand Ultra. Of the 102 runners representing 22 countries who started the event, 78 of us remained; we had one-and-a-half days, and only 34 miles, still to go.

One of the guys snored. But it was neither his noise, nor the cold and hunger, that kept me awake and shivering most of this night. It was anxiety, coupled with dread. It was the anticipation of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, of failing at something for which I had worked so hard and had come to care so much about.

Jesus, I could really blow this, I thought.

At daybreak, I had to get up and try to run—try to win—Stage 5 in this six-stage, weeklong self-supported race. It would be 26.5 miles of challenging terrain, in high heat at over 6000 feet altitude, through a narrow slot canyon, over deep-sand-covered backroads, up a dry rocky riverbed, and through a cross-country stretch void of trail and tangled with prickly vegetation. This day’s route would end with about six miles of hard-packed road, so those who still had energy in their legs to run would indeed run and pass others.

That’s what I intended to do—to run the final miles and be a closer, finishing strong, as I had in the prior four stages. I had earned the place of first-place female against some other tough ladies. What I really wanted, however, was a spot in the top 10 overall because I felt strongly that a woman’s name should be listed among the top 10 finishers, for the sake of being a role model and encouraging other women to try this branch of ultrarunning. (About one-third of the Grand to Grand Ultra’s participants were female, and I was the only chick in top-10 territory.)

Suddenly, however, my top-10 spot was in jeopardy because of an unfortunate penalty earned after Stage 4. I felt like shit, physically and mentally.

“It’s just a marathon,” I told myself about Stage 5. But I seriously doubted whether I could run Stage 5 at all; or, if I did run, I pictured myself passing out and not finishing. After four days of feeling nearly invincible, the past 12 or so hours had left me feeling depleted and decrepit, on the verge of a DNF.

Let me back up and explain why and what led to the whole penalty thing.

How Did I Get Here?

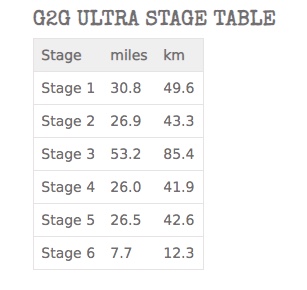

The Grand to Grand Ultra’s route profile.

This story begins with me facing my 50th birthday and wanting to give myself a gift that would make me feel younger, stronger and wilder. I had competed in the Grand to Grand Ultra in 2012 and 2014, and its sister race the Mauna to Mauna Ultra in 2017. Each one of these weeklong, off-the-grid experiences—combining ultrarunning with camping—fulfilled and strengthened me in a way that’s hard to adequately articulate. It built my confidence to do things in my 40s that I might not otherwise have believed in myself enough to do, such as write a book, take a leadership position on a board, and build a house. I wanted to do it again in part to see how I would fare compared to when I last raced it at age 45 in 2014. Mostly, I wanted a week to be alone with my thoughts, detached from devices, to contemplate how much my life has changed in the past five years and to figure out what I want to do in my 50s. It would be the gift of a retreat.

I had finished 3rd female in 2012, 2nd in 2014, and 3rd at the Mauna to Mauna. This year, I came to compete primarily with my younger self, not with other competitors. (I didn’t even know who else would show up to compete, and it turned out there were some legit female ultrarunners and stage racers who would’ve intimidated me if I had known about them ahead of time.) For each day’s stage, I set a personal goal time that felt aspirational but achievable based on how I ran those stages in the earlier years.

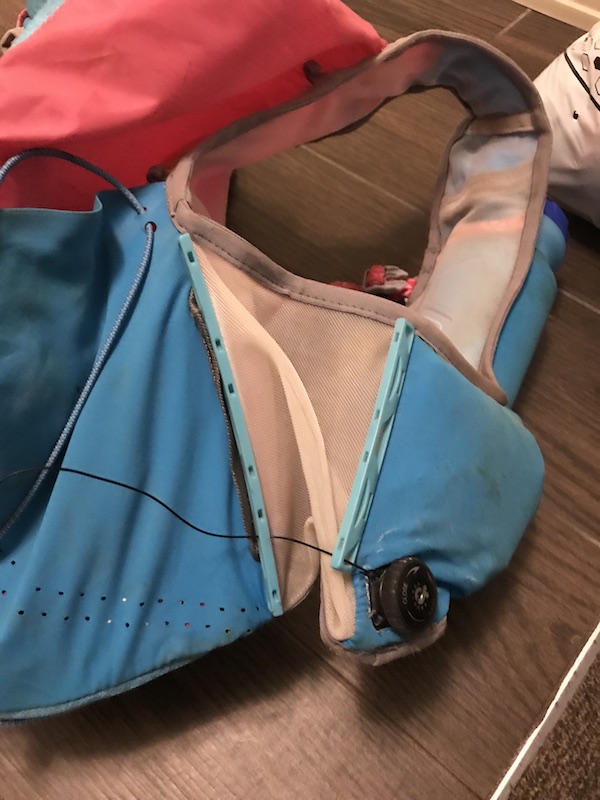

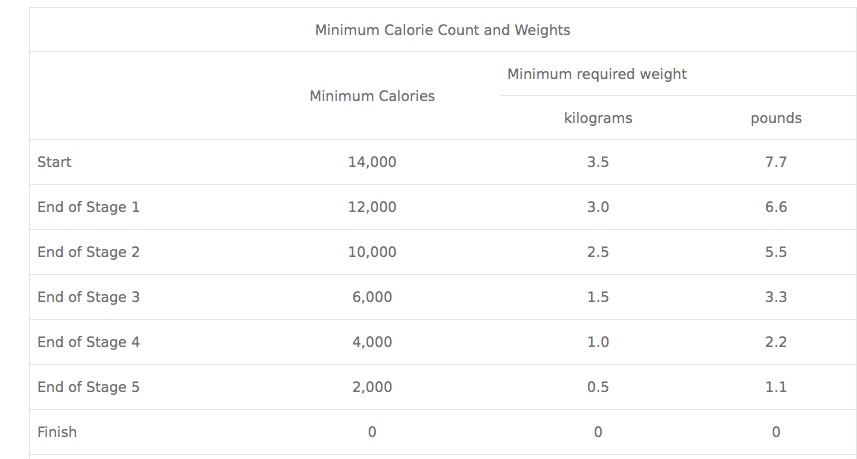

This year, I was determined to pack and eat smarter so that I could have as light of a pack as possible. (Competitors are responsible for carrying all their food and gear; the race provides only water, communal tents, and sunscreen and electrolyte tablets at checkpoints.) Whereas in the past three stage races, my pack weighed slightly over 20 pounds with full water bottles at the start, this time, I’d get it down to 17. My last post describes in detail the gear I took, and this link shows the daily food (the nightly dinners being dehydrated Mountain House brand backpacker meals).

I got my food supply close to the minimum requirement, to just over 14,000 calories. My food weighed 8 pounds exactly, slightly above the required weight. The day before the race while in Kanab, however, I started second-guessing my choices, because 2000 cals/day ain’t much when you’re burning many more thousands of calories during each stage’s run. I typically eat 2500 or more calories per day in normal life.

Consequently, I shoved a few extra snacks into my pack—an extra pack of ProBar chews, one more Clif nut-filled bar—and I also took fresh fruit from the hotel with me to camp to supplement the first morning’s breakfast. Therefore, I started with a few hundred more calories than the spreadsheet shows, but still, I knew in the back of my mind that I was taking a gamble with this minimalist approach.

My tentmates and me at Camp 1, before the start, still fresh & clean: (L-R) Jo from the UK, Ruby from Australia, me, Kevin from Pennsylvania, Julie from Colorado, Frank from Kentucky, Joe from California

Stage 1: I set off with the other competitors from the north rim of the Grand Canyon and found my groove. It helped that I ran behind a guy, Pete Daw, who had the five Grateful Dead dancing bears sewn on his pack, so I spent a good hour trying to remember every Dead song’s lyric that I could. “Sunshine Daydream” became a mantra as I ran in the strong desert sun and let my mind wander. When I tired of singing Dead songs in my head, I played a version of the alphabet game in which I tried to remember every friend I could whose named started with that letter, and then I spent five minutes or so deliberately cogitating on memories of each person. I savored the C’s (Colly, Clare, Claudia, Christine, Cheryl, Carolyn, my horse Cobalt …). I soaked in the views of the red-hued bluffs that make up the Vermillion Cliffs National Monument, and I felt proud that I had embarked on a fundraiser that raised more than $10,000 to protect these national monuments and other BLM-managed public land.

Running next to the Vermillion Cliffs National Monument

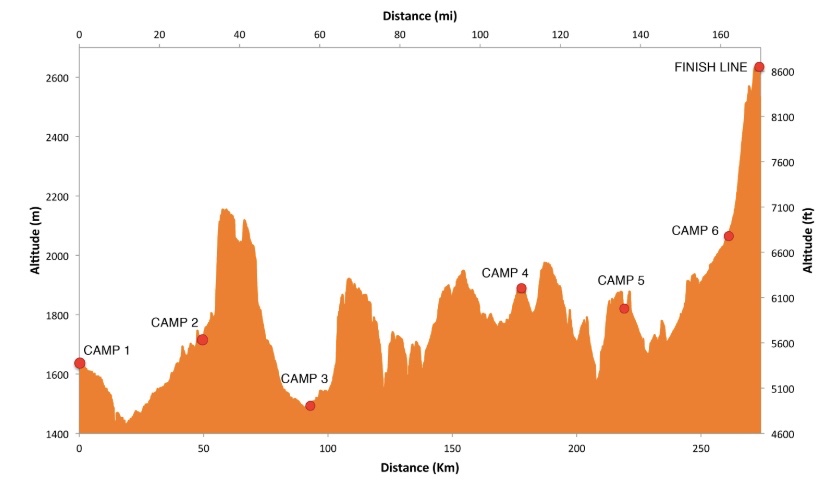

That alphabet game put me in a positive mindset so that I could handle the annoyance of my pack problem. I liked the fit and size of the Raidlight 24L pack, but right from the start, a sharp piece of plastic, which holds the cable cinching system, started poking into the right side of my lower back. I tried to bunch up the fabric of my shirt and shorts under it to create a cushion, but still it poked and eventually broke my skin. Then, about three hours into Stage 1, I suddenly felt a loosening around my rib cage, and the pack began to bounce on my back. What the…?! I looked down in horror to see that the pack’s cable had broken, so it no longer could tighten for a snug fit.

Well, that sucked. I’d have to keep running and try to ignore it. Adaptability is key to success in this wacky sport that presents unforeseen challenges. (Later at camp, I fixed both problems: I used a glob of duct tape to soften the pokey part of the plastic, and I used the drawstring from my shorts to cinch the side of the pack back together, like the lacing on a corset.)

The side of my Raidlight pack showing the broken wire that no longer cinched up the side, and the vertical plastic piece on the left that dug into my lower back. I took this photo after the race to send it to Raidlight.

I finished Stage 1 happy and relatively relaxed, not suffering the way others did on the stage’s final cacti-choked cross-country hill climb. I was 2nd female and 15th overall; a German woman age 28, Kathrin Atzor, has speedy road-running legs, and she had smoked Stage 1’s runnable hard-packed roads. She finished 24 minutes ahead of me. I didn’t care; all that mattered to me was that I had set a goal of running Stage 1 in 6:45, and I beat my goal by one minute!

Stage 2: My Colorado mountain-running legs and lungs did me proud on this stage. I started out in the middle of the pack, letting others blow their wad in the early miles through pastureland filled with more cacti, rocks and other tripping hazards. I saw the RD Colin Geddes at the first checkpoint, and he looked puzzled because I was relatively far back, so I told him, “I’m being calm and careful.”

Then we hit the Navajo Trail, an old shepherding and Native American trail that climbs more than a thousand feet to the Kaibab plateau. The vegetation transitions from desert scrub to piñon and juniper forest. On that trail, I cut loose and powered up, and I lost count of the number of runners I passed. I passed Kathrin, who was wilting in the heat and breathing hard in the thin air, and I gave her encouraging words after she told me, “I’ve never done anything like this.” When the single-track Navajo Trail gave way to a doublewide forest access road on the top of the plateau, I ran harder, feeling fantastic.

Pretty soon, I caught up to a young Australian woman with dark hair, Jacqui Bell, age 24. I didn’t know much about Jacqui, but I figured she must be hot shit because she has a sponsor that had paid for a filmmaker to follow her along the course all week for some documentary project. (That filmmaker increasingly began to film me too, presumably to build a narrative in which I’ll be portrayed as the rival.) After the week’s race, I would discover that she’s something of a media darling, with a sizable Instagram following and articles about her like this. She has raced a half-dozen or so self-supported stage races around the world and is a top competitor. It began to dawn on me that she’d be the one to beat, more so than speedy Kathrin, because Jacqui has a wealth of stage-racing trail experience.

When I passed her, we spent time talking about life and about the trail—she’s fun to talk to and extroverted. Then I pulled ahead.

I bombed down from the Kaibab plateau and transitioned to hot, flat running on desert dirt. I found my grind gear, minimized walking breaks, sang more songs in my head and passed a lot more people. I finished Stage 2 1st female, 7th overall; my goal that day had been to finish in 6:45, and I did it in 6:10, way faster than in 2012 and 2014! The overall standings for the first two stages combined placed me as 1st female, 8th overall. I had built an 11-minute lead over Kathrin, and a 1 hour, 9 minute lead over Jacqui.

But I knew that my lead could evaporate because anything can happen on the make-or-break Stage 3, the 53-mile long stage.

Fast finish on Stage 2’s flatter, open desert stretch.

Stage 3: This stage is an extraordinarily hard 50-plus-miler because of the great variety of challenges it presents. It starts with a hard-packed runnable 6 miles, so you gotta go out relatively fast to bank time before the slower miles that follow. Then you climb 1000 feet straight up a vermillion bluff, then transition to sandy tracks through rolling desert hills framed by beautiful, bizarrely sculpted rock formations. Then you plunge into a hot, densely vegetated riverbed canyon, then climb an overgrown and rocky mountainside, then more rolling sandy tracks, until the halfway point that pops out at the Best Friends Animal Sanctuary outside of Kanab. This is a lovely spot with several miles of runnable roads, so it’s imperative to run as best as possible before the sand-slogging resumes.

Then in the second half of the route, we faced the formidable Pink Corral Sand Dunes State Park, followed by a densely vegetated cross-country section that in past years I nicknamed Hell’s Garden, then more and more seemingly relentless deep-sand tracks.

One of the innumerable interesting and beautiful rock formations we ran past in Stage 3.

In the 2012 and 2014 editions, I had finished the long stage in under 16 hours. I set a goal for Stage 3 to average an 18-minute/mile pace and finish just under 16 hours. While this pace sounds quite slow, I knew it actually would be ambitious, because my pace would slow to only 2 to 3 miles per hour (a pace of 20 – 30 minutes/mile) while crawling up the dunes and hiking up un-runnable mountainsides and through deep-sand tracks.

Stage 3 started in two waves. The majority of participants took off at the normal time of 8 a.m., but the top runners—10 guys, and the top two women, Kathrin and me—had to wait to start until 10 a.m. (The organizers do this mainly so the checkpoint volunteers have time to set up the later checkpoints before the frontrunners arrive.)

I was pretty bummed to have to start in the late 10 a.m. wave; it’s noticeably hotter by mid-morning, and we have two hours less of daylight in which to run. Plus, it’s draining to sit around camp for an extra two hours while the minimalist breakfast digests and the stomach starts growling. I tried to cease my bellyaching by focusing on the advantage: that it’s fun and inspiring to catch up to the first-wave starters and to chat with them while passing.

While sitting around camp waiting to start, and realizing that the forecast called for hot temps that would feel even hotter in the full sun reflecting off the light-colored sand, I realized I would benefit from more calories than I budgeted for the long stage, since my body would be under more stress today. I therefore made a fateful decision to use an extra pack of GU Rocktane drink mix (250 calories) and a bag of potato chips (approx 140 cals) that were budgeted for later in the week. I transferred those rations to my snacks for the long stage, and sure enough, I was glad I had that mid-run fuel. But this seemingly innocuous decision would come back to haunt me.

I rocked the first 40 miles of the long stage. It’s kind of crazy how 40 miles in those conditions can feel so manageable. Clearly I was doing something right, because the day felt magical. I loved meeting and passing the first-wave starters and cheering them on as they complimented me.

Climbing a bluff at around miles 7 – 9 on Stage 3. (The mountain had a nice trail; this was the only place we had to scramble and use hands on it.)

This photo below was taken by Dale Cougot as I passed him in the afternoon. It shows the typical sand we ran through during most of Stage 3; in many places, the sand was much deeper than pictured here. I wore full-sand gaiters over my shoes, and they did a good job keeping the sand out.

Running Stage 3 around the midway point; photo by Dale Cougot.

When the sun finally went down, I relished the 90 minutes of twilight when the heat of the day finally cooled off but we still had enough daylight to see. At this point, I was in the midst of an 8-mile stretch with super soft, deep sand leading up to the sand dunes. I looked at the time on my watch, did the math, and realized I was falling behind my sub-16-hour goal; but, I didn’t think I could do any better or go any faster. I felt I was pushing as much as I could sustain. I could only conclude that the sand was playing more of a factor this year in slowing down me and others.

I never saw Kathrin; she stayed behind me from the start, and I heard from checkpoint volunteers that she was struggling. I began to stoke a desire to win this long stage, but I had no idea of where Jacqui was or how she was doing because she started during the earlier 8 a.m. start, and I hadn’t been fast enough to close a two-hour gap. I asked about her at checkpoints, and the volunteers said, “Jacqui is doing great—and Birgit is really on fire.” Birgit Mitchell, 48, is from Austria but lives much of the time in Washington D.C. and trains with Karl Meltzer. She’s an experienced ultrarunner who’s finished several “Beast Coast” 100-milers. I genuinely liked her and was glad she was doing well.

The stars began to appear, so I got my good headlamp out of my pack. In my first “oh-shit” moment of the day, I discovered that the headlamp wouldn’t turn on. Either it was stuck in a locked mode that I couldn’t figure out how to unlock, or it had turned itself on in my pack and drained the fresh batteries. I had one more set of spare batteries but didn’t want to hassle with digging them out from my pack. I therefore got the not-so-great second headlamp I’d been using at night at camp and hoped its batteries would last.

At Checkpoint 6, mile 40, I left with my new friend Ilan Freiman who’s from Australia but lives in Hong Kong. We ran along the highway approaching the Pink Corral Sand Dunes State Park, and I felt in high spirits, eager to attack the two-dozen-plus sand hills that I had conquered in past years. They are insanely steep and soft. Ilan was under the misimpression that there’d be only a half dozen or so sand hills. I told him we’d face at least 20, probably more, and he seemed shocked. “Let’s count them!” I suggested, so we did.

A few of the dunes as seen by day; Ilan and I traversed them under a star-filled moonless sky.

The first one we could hike, but then we had to plunge our hands into the second one, which sloped like a ladder and rose at least two stories high. I punched my fists into the sand and started to bear crawl. Up up up we crawled on this wall of sand, briefly slipping backwards before regaining forward momentum, gasping for breath, finally reaching the top and pausing on hands and knees.

“That’s two!” I said. “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time!”

We slid down the backside of the dunes, strained our eyes to spot course markers in the distance, and progressively scrambled up each one. At one point, while bear-crawling, I placed my fist next to a tarantula as big as my hand. I didn’t flinch, just like I didn’t mind when I saw a snake stretch across the trail earlier in the day. The creature seemed cool, and nothing could scare me.

The Milky Way on a moonless night illuminated a swath of the star-filled galaxy and made me feel supernatural. We counted 32 dunes.

Eventually the dunes transitioned to a deep-sand track with mild hills. We caught up with Ann Verhaeghe, 55, from Belgium, one of the top-5 women. I wondered how far ahead Jacqui and Birgit could be. Gradually, I pulled ahead and left Ilan and Ann to run together. Then I followed the course markers to make a right turn off the track into the snarl of Hell’s Garden.

I don’t know the proper names of these desert plants, but imagine being surrounded at night by small trees and bushes with spike-covered branches. Mounds of dead wood and other rotten foliage mix with rocks and low-lying cacti to create an uneven, sharp footing. There is no such thing as a trail to follow. Occasionally, the ground gives way and drops 8 feet down a sandy bank into a gully wash, making for a scramble up the other side. My dimming headlamp could barely catch the reflective glow of the pink course ribbons in the distance. Each ribbon is a lifeline; if you can’t spot the next marker, you’ll be entangled and disoriented until daybreak. I kept stepping forward, accepting the scratches on my legs while elbowing and clawing the branches away from my face. At one point I tripped and almost face-planted into the carcass of a decaying sheep.

Suddenly, a shiny obstacle came into view: a tall barbed-wire fence that looked fairly new. All day we had passed through fences managed by ranchers and the BLM; when no gate presented itself, a helpful sign instructed us to climb over the fence, and a stump or some other obstacle aided the climb. But this fence had no gate, no sign, no stepladder—just razor-sharp wire about 5 feet high, attached to metal stakes that did not provide any footholds. The course markers clearly advanced on the other side of the barbed fence. I looked around, disbelieving. Is this a joke, a trick? Finally I concluded we had to get through it, so I could choose to go over or under.

Not trusting my coordination to climb, and not wanting to shred my legs, I chose to go under. I took off my pack, threw it on the other side, and got flat on my belly to squeeze through the 18-inch-high gap between the ground and the first row of barbed wire. I found myself eye-to-eye with ants and beetles, and I felt sand on my cheek. I pondered internally, Who does this kind of shit at 1:30 in the morning? Then I roared out loud, “I DO!”

I got through the vegetation, I got through the final checkpoint. I knew sub-16 hours was out of reach, but I kept pushing. During the final three miles, I began to imagine the sand might be quicksand, grabbing my legs and holding me back, as if in a nightmare when you try to run but feel you’re struggling to swim.

Finally, around 2:40 a.m., I saw the white tents of camp and crossed Stage 3’s finish line. It took me 16 hours, 41 minutes, placing 1st female and 8th overall for that stage. Birgit came in at 17:03 (plus she got a 15-minute penalty for leaving a piece of gear behind at a checkpoint—ouch!), and Jacqui at 18:10. About half the competitors took 24 hours or longer to do the long stage, stopping to sleep and eat meals at checkpoints along the way. The race schedules two full days for Stage 3, so I could spend the second day (Wednesday, September 25) relaxing and recovering in anticipation of Stage 4.

After some sleep and daybreak, I felt satisfied and strong, but increasingly hungry. During the recovery day, I lay in my tent listening to a woman one tent over give away all her food because she had dropped out during the long stage and was heading home. I felt “hangry,” because it’s against the rules to give away food like that.

When someone that afternoon kindly offered me some of their food, I politely but firmly declined. “It’s against the rules, and I don’t want to jeopardize my spot,” I said. Hearing myself, I realized I had come to care a lot—perhaps too much—about winning.

At the start line of Stage 4, we collectively got into warrior mode. I’m on the far left, behind Ana with the orange headband. Jacqui is on the far right.

Stage 4: Today was “only” 26 miles. I entered it in 7th place overall and 1st female with a comfortable lead. We faced more long sandy stretches in the heat, a climb so steep up a rock wall that we needed to use a fixed rope for assistance, a scramble up another mountainside covered with prickly vegetation, a traverse over uneven slickrock, then a fast finish on a hard-packed gravel road that I psyched myself up to run as fast as possible.

I ran the first portion of Stage 4 with a Portuguese man named Nuno, and I practiced speaking Spanish with him. He taught me that the word for “shade” is la sombra.

I wanted to run strong today, so I ate some of my food budgeted for later that night at breakfast; for example, I used my hot cocoa pack to make a delicious mocha with my instant coffee ration. Little did I know that this decision, coupled with the earlier decision to use some of Stage 6’s food on Stage 3’s long stage, would bite me.

I felt pretty good until the heat started reflecting off bright-white sand and my skin prickled in the sun. I caught up to Jacqui about one-third of the way through and enjoyed doing the rope climb and navigating the cross-country hillside scramble with her. We fell into an easy and supportive conversation. Eventually I pulled ahead. I wanted to catch Kathrin, whose speedy legs had returned, but she remained in the lead for this stage.

Climbing a rock wall in Stage 4.

Stage 4’s beautiful slickrock traverse.

Climbing out of a canyon toward the end of Stage 4. “Are we there yet?”

I reached the finish line of Stage 4 still feeling strong and confident. My goal had been to run it in 6:15, but I had slowed down in the heat, finishing second female in 6:32, 10 minutes behind Kathrin.

Then my confidence evaporated, because race commissioner Garth Reader told me and everyone else as they crossed the finish, “Bag check. I need to see some mandatory equipment and weigh your food.”

I dumped out the contents of my pack. I had the knife, safety mirror and emergency blanket he wanted to see. But when it came to measuring the weight of my food, I knew I was on thin ice.

“This is way too light,” Garth said. I pointed out that I had enough calories at the start, but he said that didn’t matter; I was short of the minimum required at the end of Stage 4. He referred to the chart printed in our race booklet:

The punishment: a one-hour time penalty.

I couldn’t believe it. The extra hour knocked me from 7th overall to 10th, and the guy in 11th could take me down. I pictured my family and friends, who were tracking the race results online, seeing my time from Stage 4 equalling 7:32 instead of 6:32 due to the penalty, and they would wonder why I had slowed down so much. I felt horrible.

The only thing that made me feel slightly better is I had company. Jacqui, Ilan and a couple of others also got one-hour penalties for being light on food.

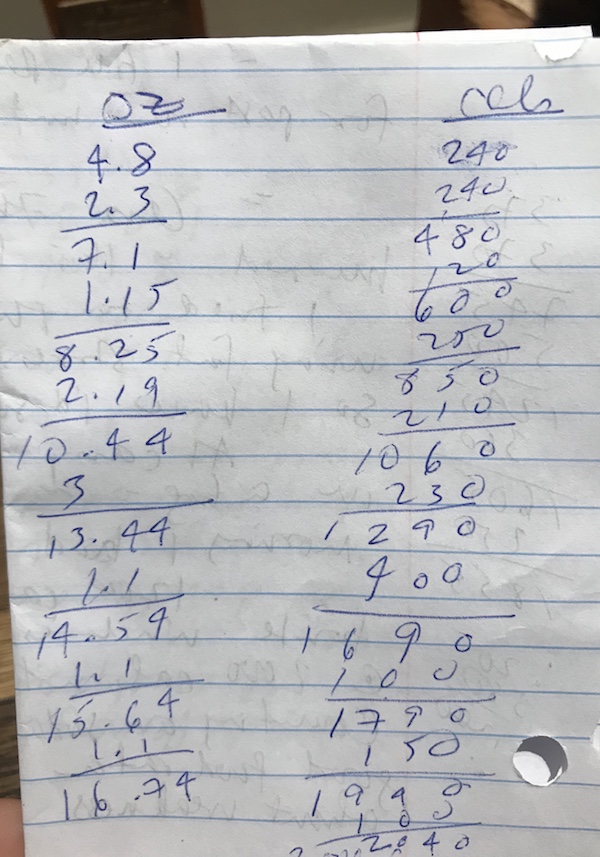

I went to my tent and took inventory of my measly supplies. I knew we faced at least a 50-50 chance that Garth would inspect us again after Stage 5, and I needed to have the required 2000 calories and 1.1 pounds of food after the next day’s challenging marathon-length run.

I frantically added up the remaining calories and ounces. The only way to make it work, I concluded, was to restrict myself to a tiny breakfast and minimal calories during Stage 5’s run so that I would have enough left over to pass inspection after Stage 5.

My manic food calorie and weight tally that I computed during the afternoon following Stage 4.

I solemnly nursed my allotted dehydrated-meal-in-a-bag and went to bed, which led to the nighttime scenario described in the opening: cold, hungry, wide-awake and catastrophizing.

Given how depleted I felt, how the hell could I run a strong 26.5 miles for Stage 5 over rough terrain on only a 210-calorie oatmeal packet for breakfast, and then one 100-calorie GU gel and one 250-calorie GU Rocktane drink mix pack for the whole stage? The run might take up to 7 hours, and I’d have only 350 calories for the stage. As a coach, I advise my ultrarunning clients to take in 200 calories per hour after the first hour of their long run.

I lay in my too-thin sleeping bag, cursed my deflated sleeping pad, and visualized myself passing out and waking up on a medical cot with an IV in my arm, which would automatically disqualify me.

Shivering, I began to fantasize about climbing into my tentmate Ruby’s sleeping bag to spoon. I wondered which card to play: “I really want to be with you tonight” vs. “I’m experiencing pre-hypothermic symptoms and need your help.”

Earlier, while running Stage 4, I had contemplated answers to the phrase, “You know you’re a self-supported stage racer when…,” and I had come up with replies such as, “You know you’re a self-supported stage-racer when you eat your dirt boogers because you crave salt and you’re so hungry.” On this night, I added to the list, “You know you’re a self-supported stage racer when you contemplate committing infidelity for the sake of body heat instead of sex.”

Ultimately, I decided Ruby needed her sleep, and I didn’t want to freak her out. So I lay in my hard-dirt pod and fantasized about my friend Clare Abram’s home-baked bread. Then I recalled how Clare and I had munched on quesadilla triangles during the final 20 miles when she paced me in 2016’s Western States 100, and I thought about how quaint and cushy those aid stations made 100-milers seem, dishing up a buffet of sweet and salty food. If only.

I finally fell asleep for a couple of restless hours by telling myself, “Have faith that your body can do more than you think it can.”

I woke up with teeth chattering. I started to get dressed for Stage 5 and told my six stalwart tentmates, “You guys, I really need a pep talk today, because I don’t know if I can get through this stage without collapsing and DNF’ing.”

They rose to the occasion. Kevin exhorted me to believe in myself. Julie made me laugh with more raunchy comments about our “lady bits.”

Ultimately, however, it fell upon a wonderful woman named Michele Santilhano to give me the kick in the pants I needed. I told her at the start line that I felt weak, hungry, and that I doubted I could run.

She looked at me disbelieving. “Think of the slaves and how they suffered,” she said. “As long as you have hydration and electrolytes, you’ll be fine. You could keep going for 40 days.”

Then she repeated, “You’ll be fine.”

That was precisely what I needed to hear. I would suffer, but I would be fine. I could do this.

Finding Transcendence in the Final Stages

Stage 5: I took off running in a sandy track with the others toward this stage’s highlight: Peekaboo Slot Canyon. We plunged down a hillside and entered the riverbed. Crimson-hued rock walls, tall and curvy and streaked with blond highlights, rose up on both sides, and the rocky riverbed began to narrow to a thinner ribbon of a trail. The more the trail narrowed, and the taller the rock walls became, the more anxious and claustrophobic I felt. I took comfort in running wordlessly in rhythm with Birgit, feeding off her energy and camaraderie. I broke the silence to tell her my mantra was, “Calm The Fuck Down.”

Feeling freaky in Peekaboo Slot Canyon.

I navigated the ladders we had to descend in the canyon’s steepest drop-offs, I scooched over big boulders, and I emerged from the canyon feeling pretty OK. Jacqui, Birgit and other women were ahead, but Kathrin was behind because the canyon’s obstacles had slowed her down. Then I settled into slowly running another stretch of sandy track.

I had one bottle full of the GU Rocktane drink mix, and one GU gel in my pocket. I vowed to save the gel until after four hours. I wondered how long I could nurse the 250-calorie bottle of sports drink. I took a sip, swished it around my mouth and swallowed. I decided to have a sip no more frequently than every 20 minutes, so that it would be like a slow glucose drip. My mind darkly dredged up a story I’d heard about anorexic elite gymnasts who skip meals and suck on Jolly Rancher candies to get through workouts, and I thought, If they can do it …

The heat beat down. I kept running the sandy tracks. I got the songs Staying Alive and Running on Empty stuck in my head.

Finally, gratefully, I caught up to Jacqui and felt almost giddy with happiness for her company. We started talking girl talk and gossiping about other competitors. Looking at her, I tried to remember what I was like at her age, when I started running in early 1994 a couple of months before my 25th birthday. Would she still be doing this a quarter-century from now, like me? Would I, at 75? I hoped so.

We traversed miles of dry, rocky riverbed and hiked up a super steep mountainside. I wanted Jacqui to hang with me, but she fell behind as I pulled ahead.

In the second half of the stage, the course diverted from the sandy track to a cross-country section introduced this year. Since it was a new part of the route, I didn’t know what to expect. Given that the Grand to Grand seems to strive to make the route as difficult as possible, I should have known it’d be tough. Sure enough, these three or so miles seemed like a daytime version of Stage 3’s Hell’s Garden, except it also featured a scramble up a steep hillside covered with desert scrub—a climb that I later heard made some people sit and cry. I scrambled up it and followed the route to its final six or so miles of runnable hard-packed dirt and gravel.

I took one of the final sips of the remaining sports drink. Amazingly, I felt no hunger. I felt no pain. I felt fine. I felt—it hit me—transcendent.

We ultrarunners like to talk about “transcendence,” but I don’t think I had ever really experienced it before now. Here, I transcended doubt, discomfort, emptiness. By giving this race everything I had, I reached a state of flow and fulfillment.

I stepped over a three-foot-long stretched-out snake in the roadway and barely cared. I took a swig of plain water and spit it into my buff to cool off my neck in the full-strength sun. Then I tore open and swallowed my single 100-calorie GU gel. I was going to finish this thing as fast as my body would allow.

Running a hard-packed stretch about five miles before the end of Stage 5.

I began a steady pattern of run/walk intervals on the runnable road, using the course markers as measurements. Run past three or four course markers, then take a walk break to the next one. Using this method, I caught and passed a British man named Simon, who was vying for 11th place overall. After the final checkpoint, I built a couple minutes’ gap on him.

Before this stage’s final mile, as the white tents of camp started to come into view, I looked over my shoulder to see how far behind Simon was. But the person behind me didn’t look like Simon. It appeared to be Kathrin. Her roadie legs were eating up these final runnable miles, and she wanted to catch me before she ran out of real estate. Not today.

I ran that final mile as if finishing the Boston Marathon. I reached camp in 6:35, first female and a minute-and-a-half in front of Kathrin. In the overall standings, I still held onto 10th place, with a 55-minute lead over 11th-place Simon.

When I asked Garth if he was going to inspect my bag again, he said, “No, don’t worry; go ahead and eat whatever you have.” I gleefully started to eat and drink the calories that I would have used during the run—a GU Stroopwafel, another packet of Rocktane drink mix (which I chugged!), and then my recovery drink mix.

Michele predicted that I would be fine, but I felt fantastic.

Stage 6: Only 7.7 miles of trail stretched between the final camp and the finish line. We woke up knowing we’d be done by noon. We all got dressed and ate breakfast with a touch of melancholy because this would be our last morning together in this wild week.

Located at 6700 feet elevation, the final camp was downright chilly on the overcast autumn morning. I put my long-sleeve wool base layer on under my race shirt, and I wore my buff around my head instead of neck to keep my ears warm. The route would climb 2000 feet on forest road and single-track trail, through the Dixie National Forest hugging Bryce National Park.

The race director divided the competitors into three staggered starting waves, the fastest group starting latest, so that we would all arrive at the finish line within the same window of time. I therefore got to linger at camp, wrapped in my down puffy and emergency space blanket for warmth, and savor the company of the frontrunner guys whom I’d come to know and like.

At last we took off. Kathrin was the only other woman assigned to this final starting wave. I knew I didn’t need to run hard—my place was secure, I could walk it in—but in the cold air, with the excitement of reaching the finish, I felt frisky.

As we began ascending a forested mountainside ablaze with golden aspens, my emotions started to bubble to the surface. I felt gratitude and love for my body—a self-compassion that I rarely experience. This back, which three months earlier had been in such pain from a fractured vertebra and strained muscles, had carried my pack for a week. These legs, whose hamstrings usually stiffen and ache, had transported me with nary a complaint for 170 miles.

When the lumpy, crimson-colored rock spires called hoodoos came into view, the route turned onto the aptly named Grand View Trail. We were approaching a summit that overlooked the pink cliffs of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

I increased my pace on the singletrack and reflected on a question that had prompted me to go on this “retreat”: What am I going to do in my 50s? This, I realized. This is what I do, who I am, where I find friends. This is my thing. It’s not my only thing, but it drives and improves every other thing that I do. You do something long enough, you eventually get good at it. Simple as that.

I came around a corner and saw a throng of competitors and volunteers cheering, and I heard the words “2019 Grand to Grand Ultra women’s champion” on the loudspeaker.

Stage 6 finish, 170 self-supported miles done!

I finished first female in Stage 6, five minutes ahead of Jacqui and Ann who tied for second in the final stage. Overall, I won the women’s race and came in 10th place with the men, with a cumulative time of 45 hours, 34 minutes (which includes the one-hour penalty). Even deducting that extra hour, I was a couple of hours slower than in 2012 and 2014; but, the course conditions seemed noticeably different (the sand softer, the daytime temperatures hotter, the cross-country sections wilder), so perhaps it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Jacqui finished 2nd woman and 14th overall in 48:30. Joseph Taylor of Salt Lake City won the men’s race in a blazing 34:16. Full results here.

Holding my third Grand to Grand Ultra buckle, presented to me by Tess and Colin Geddes.

I embraced the race directors, Tess and Colin Geddes, and thanked them for creating an event that has changed my life.

Celebration Gallery!

Some favorite shots from the finish and the awards celebration:

With my new Australian buddies Ilan and David

Laughing with the ladies of Tent 11: Ruby, Julie, Jo

With Ruby and Frank

Garth, the rules commissioner, threatening to give me another penalty.

With Jacqui—I have so much admiration for this young woman.

With Birgit, who finished 4th and won her age group.

With David, who finished in 6th place.

With men’s champ Joseph

My two very special trophies, which feel kinda like lifetime achievement awards. The little one was a special prize for being the first three-peat alumna.

A thorough, and thoroughly inspiring, race report! I may never run this far, but reading about your adventure encourages me to stretch my own running limits. Congrats!

Bravo Sarah!

What a wonderful race for you – thank you for taking us through the course physically and emotionally.

You deserve this one. Relish and admire this win – It’s incredibly impressive.

You’ve more than inspired me to continue running strong into my 50s next year.

Steve

Wow, what a race. And what a report! Congrats on both, from a fellow runner on a different continent.

This was a tremendous read!! You are amazing!!

I just ordered your book and am now browsing your website and found this blog post. I am just starting out running and am training for an ultra marathon. The Grand to Grand Ultra race is the reason I wanted to pursue this goal and I love that you have just run it! I will be soaking up your information and story. You are inspiring and I hope to be running this race like you in a few years!!