Earlier this year, I embarked on a mission to raise funds and awareness for the Conservation Lands Foundation, to help protect and enhance some 36 million acres of public land, mostly in the West, that contain incredible scenery, nature, history, culture and archeology. Given the current political climate and the attacks on laws meant to safeguard these lands, I believe the foundation’s work is needed more than ever. The story below highlights just one national monument that the foundation works to defend, and where it’s making a difference. Please visit my fundraiser page after reading this post.

Standing on a mass of layered terra-cotta-colored sandstone, overlooking an immense horseshoe-shaped canyon, we surveyed our destination: an outpost of lumpy rock that touched the sky and towered over its surroundings. A naturally formed wall shaped like a bridge connected the rock island to where we stood. Awed by the sight, I fortified myself to traverse that land bridge and climb up rocks in the distance to explore a place that had been home to many.

Mother Nature created a citadel—a fortress high above the ground—in this remote spot in southeast Utah, and the native people whose society thrived here more than a millennium ago recognized it as an ideal place to call home because of its protective qualities. And so they built dwellings tucked into the rock to live in, and granaries to store their corn, and centuries later, I found myself marveling at the beauty, spirit and wildness of this place.

This place is Bears Ears National Monument, and my husband Morgan and I explored parts of it during a few days in May for several reasons. Mostly, I wanted to find out what’s so special about Bears Ears in particular and national monuments in general, and why this area became a flashpoint in national politics. I also wanted to see firsthand why the work of the Conservation Lands Foundation—supporting local efforts to protect and enhance the National Conservation Lands, which include national monuments like Bears Ears—is needed now more than ever.

Our small group, led by a local guide, made our way over the land bridge and hoisted ourselves up red rocks to marvel at the still-intact dwellings built sometime during the Middle Ages. Ancient wood beams supported the windows, held in place by twine made from yucca. A few desiccated corn cobs and small, broken pieces of pottery lay on the ground.

It’s simply awe-inspiring to stand in a place like that and imagine the hard-working, resourceful indigenous people who raised families and sustained themselves here, totally in synch with the natural world. We lowered our voices and spoke in hushed tones out of respect for the belief that spirits still live here, and as such these structures are considered “dwellings” and not “ruins.”

Getting here wasn’t easy—it involved a long drive over a washed-out sandy road, a stop at an unmarked trailhead, and a two-mile hike down a creek bed and a faint trail. Our guide admonished us to keep to the trail and “don’t bust the crust,” which means don’t step on the bumpy, blackish cryptobiotic soil that’s full of bacterial life and integral to the desert ecosystem.

I’m not going to describe how to get to here—one of the tens of thousands of unique cultural sites, spanning over a million acres in Bears Ears National Monument—because it’s important that visitors to this area first get educated about how to visit with respect, and how to access the areas in the least disturbing way. The best way is to start by visiting the Friends of Cedar Mesa Bears Ears Education Center in the town of Bluff, and then consider hiring a guide.

Visiting this spot, and viewing artifacts and rock art near other remote dwellings, I was struck by how totally different this experience felt compared to visiting Mesa Verde National Park to see Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings and other archeological sites there. At the national park, you have to buy tickets for entry and go on a tour with dozens of others, and the paths are paved with asphalt and bordered by handrails. Visiting Bears Ears National Monument, the experience felt unstructured and authentic, with minimal infrastructure.

The monument’s caretakers are engaged in an ongoing healthy discourse about how much infrastructure to build for visitors, as additional parking spaces and trail signage might be helpful to keep cars and people away from sensitive areas. But the overriding goal, it seems, is to protect the national monument in its natural state and not attract hordes in tour buses—a balancing act that’s a work in progress.

Politics, Growing Pains and Good News

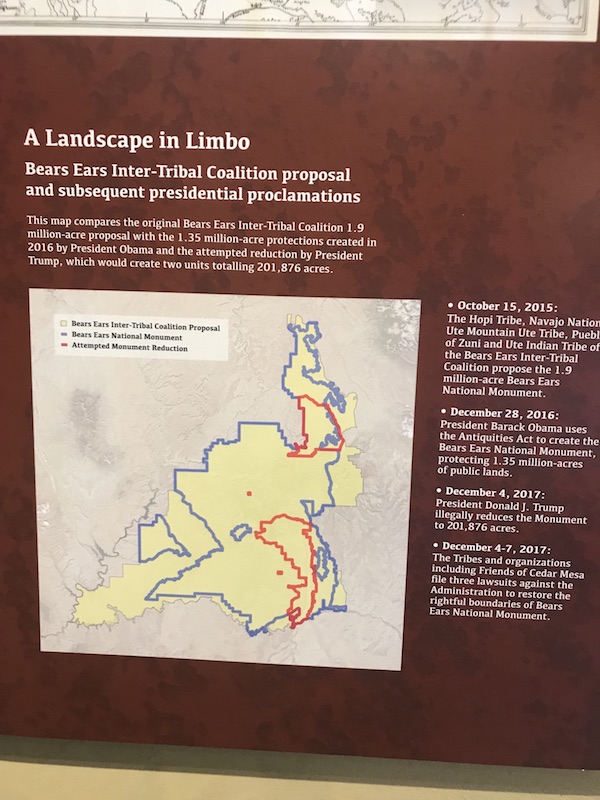

“Bears Ears”—named after two bluffs that stick up on the horizon when viewed from Cedar Mesa—entered the present-day national consciousness on December 28, 2016, when President Obama designated 1.35 million acres as a national monument, following the proposal of a coalition of five Native American tribes.

The land already belonged to the public, managed mostly by the Bureau of Land Management and partly by the US Forest Service, but monument designation gave the area greater protection, along with resources for surveying and studying the innumerable archeological sites in the area. Perhaps most important, the monument designation prevents new leases for natural resource extraction. Land use rights that existed at the time of the designation, such as grazing, are grandfathered in and allowed to continue.

The coalition of the five tribes and conservationists lauded Obama’s proclamation (although the boundary acreage, 1.35 million, was smaller than the tribes’ proposed 1.9 million). But Obama’s move in the final weeks of his presidency outraged some locals and conservative Utah lawmakers who viewed it as federal overreach that could deprive their counties of potential land use such as mining, and who rebel against regulations such as restrictions on off-road vehicles.

From my visit to Bluff and from doing research, I got the sense that many old-timers in Utah grapple with a love/hate view of us out-of-state recreation enthusiasts and environmentalists who visit—and in some cases, move to—their state to delight in the spectacular and vast public land. We visitors pump money into the local economies, but we also affect the area’s culture and politics. It’s a tension felt from Moab to Kanab to Bluff and Blanding (read more here).

I found it admirable, albeit idealistic, that a couple of the progressive newer residents in Bluff whom I met, who advocate for Bears Ears National Monument, told me they don’t want Bluff to become “another Moab” but rather, they want to manage growth and outdoor recreation within and around Bears Ears in the most low-impact and sensitive way possible.

I left here with a deeper understanding that this sacred, scenic public land is fragile and threatened—threatened by the Trump administration, which shrunk by 85 percent the acreage under national monument protection, thus taking away resources to safeguard and study the area while opening it up to potential mining and energy development; threatened by careless tourists and intentional vandals who leave graffiti next to ancient rock art and loot artifacts like arrowheads; and like everything, threatened by climate change. Even the cows that still graze here pose a threat by trampling or knocking down archeological sites.

But I did not expect to find—and was pleasantly surprised to learn—about the good news coming out of this area, which involves the impressive work to steward Bears Ears National Monument that has been accomplished by local advocates and volunteers over the past decade.

This work has been strongly supported by the Conservation Lands Foundation, which has given major funding and collaboration to the Friends of Cedar Mesa and its work on behalf of Bears Ears National Monument. Friends of Cedar Mesa, formed in 2010, is one of 70 community-based organizations that the Conservation Lands Foundation leads and supports in the Friends Grassroots Network, all of which do hands-on work to protect the National Conservation Lands and educate the public about them. Another is Utah Diné Bikéyah, a Native-led, community-based organization that also works to protect and steward Bears Ears.

The Friends of Cedar Mesa Bears Ears Education Center opened fairly recently, in September of 2018, and it’s one of the most thoughtful and interesting visitor centers I’ve seen. It’s testament to the care and activism of environmentalists, Native American tribes, archeologists and others who care about the area. They came together—in the absence of federal support—and raised some $700,000 to create a place to inform and manage the influx of visitors to the area while advocating for protection of the land and its sacred sites.

A Day to Celebrate

Saturday, June 8, marks an important day for conservation in American history: the 113th anniversary of Teddy Roosevelt’s signing of the American Antiquities Act of 1906. This act gave Obama and prior presidents the power to designate areas as national monuments, thereby obligating federal agencies such as the BLM to manage that area in a way that protects and preserves its archeological, cultural, historic and scientific characteristics for future generations. The act arose out of concern about the widespread practice in the late 19th and early 20th century of looting of these sites. Looking to make easy money, treasure hunters scoured lands for ancient baskets, pottery, jewelry—any artifacts that could be sold back East or abroad.

A century later, the Antiquities Act is under attack as the Trump administration seeks to shrink national monuments and weaken the executive branch’s ability to designate them. Conservation Lands Foundation is one of many environmental groups fighting that rollback and supporting legislation to defend the Antiquities Act.

When I process all this information—and I know, it’s a lot to take in—I feel the spirit of Teddy Roosevelt hit me, and by that I mean: the inspiration to act now for future generations. The future of Bears Ears and other national monuments matters for our grandchildren a century from now. It matters to preserve the history and heritage, the wildlife habitat, the climate, the undeveloped open space.

If you feel as I do—that the work to defend and enhance national monuments and other special areas that form the National Conservation Lands matters hugely now and for the future—then I hope you’ll join me in supporting the Conservation Lands Foundation, which is working at the grassroots, in Congress and in the courts to protect America’s newest public lands. Show your support by learning more about my campaign and making a donation here.

Recommendations for Visiting Bluff

Bluff, Utah, the gateway to Bears Ears National Park, is a very small but growing town whose population stood at only 320 at the last census. Its town sign says “Est. 650 A.D.,” acknowledging the Ancestral Puebloans’ first settlement near there.

I recommend your first stop be the Friends of Cedar Mesa Bears Ears Education Center at 567 W. Main Street.

For lodging, we stayed at a charming motel called La Posada Pintada, which served surprisingly gourmet breakfasts. For dining out, my favorite restaurant (and there are only a handful in town) was the Comb Ridge Eat & Drink. For a guide, we had a good experience with Wild Expeditions.

Finally, if you want to see an amazing multimedia presentation of Bears Ears National Monument, I encourage you to check out this special graphic project by the Washington Post, “What Remains of Bears Ears.”

Comments are closed.