Heading into the Ouray 100 Mile Endurance Run on Friday morning, July 27, several fears gnawed at my confidence, chief among them the mountain passes I had not yet scouted out and that threatened dangerous electrical storms on exposed ridges above treeline. I had spent the past couple of months training on all the major climbs in the second half of the route, but the first part remained mostly unknown, aside from the main arteries of Camp Bird Mine Road and Imogene Pass Road.

“Just get over Richmond Pass to Ironton,” I told myself, referring to the section between miles 21 and 27 over a 12,600-foot saddle with a talus field and an off-trail section where dense fog could hide course markings.

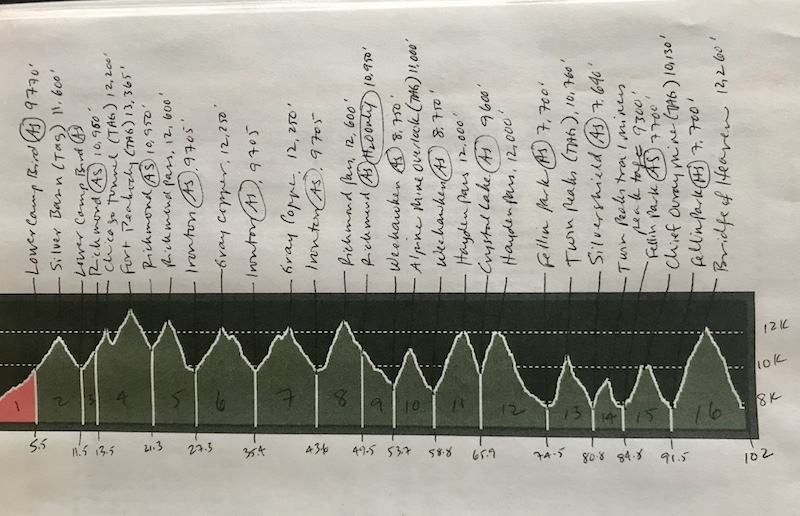

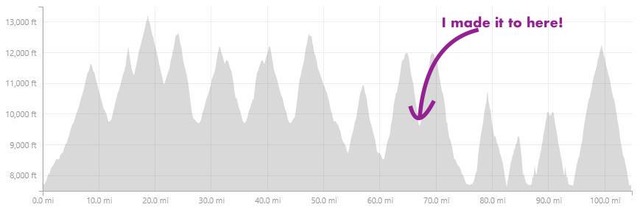

My annotated Ouray 100 elevation profile, featuring 41,000+ feet of elevation gain over approx 102 miles. Low point on course = 7700 feet; high point = 13,365.

The first half-marathon-length section, up and down the first 11,600-foot climb to Silver Basin alpine lake, went by in a comfortable blur that I barely remember, as I settled into a relaxed rhythm of briskly hiking and running any flatter and downhill portions. Then, as we headed up the second 12,200-foot peak, above the remains of Upper Camp Bird Mine, the sky turned charcoal gray and the temperature suddenly felt icy.

A shot of one of the old structures in the Upper Camp Bird mine, on our climb to the Chicago Tunnel. Photo from the ouray100.com gallery.

But I wasn’t scared or worried. This spur off the main mining road, which I perhaps visited with my dad as a kid but didn’t remember, fascinated me. I kept peering at the mining ruins—the rickety wooden remains of cabins and sheds, the dark tunnels in hillsides—and my throat tightened as I pictured my grandfather, David S. Lavender, working there in 1932 (as chronicled in his book One Man’s West).

“You think this is hard?” I asked a couple of runners next to me as we hiked while leaning into the slope, and I told them about how my grandfather and other hardrock miners worked there during the Depression. My grandpa (who passed away in 2003) operated a hoist deep in the darkness of these hillsides’ innards, until he got a better assignment in the fresh air and daylight. His “promotion” involved hammering and busting up boulders into smaller pieces, picking over the rock pile for strains of precious elements to salvage. I wondered, had Grandpa spent time in any of these buildings? Did he bust rocks around here? His spirit fortified my resolve to handle whatever challenges that the trail and weather presented.

Reading the sky, I said to a woman near me, “Time for rain pants,” and I donned my lightweight Ultimate Direction Ultra Pants just in time for them to protect my skin and retain body heat as the clouds unleashed piercing BBs of hail. I expected this kind of storm in the afternoon, but mid-morning? On only the second of 14 major climbs? A couple of other runners huddled under a pine tree, shivering, while I kept hiking up the steep grade as the sky thundered and forked lightning danced on the ridge.

Next to an ominous dark pit in the side of the mountain, called the Chicago Tunnel, we had to step out onto a sky-high ledge overlooking the alpine basin and Camp Bird Mine. The race director had placed a hole punch here, attached to a string, and we were supposed to punch our bibs with the hole punch as proof of tagging the peak. (Each hole puncher on the various peaks was slightly different, creating a specific shape to prove we made it up each section.) But the string attaching the hole puncher was so short that I had to kneel down awkwardly to slide my paper bib into the thin opening of the hole punch. My wet, frigid hands slipped and couldn’t grip or squeeze it to make a hole. Blasts of thunder like bombs rang in my ears, and lightening crackled nearby. Good grief, is this how I’m gonna die, trying to punch a hole in a piece of paper on a rocky ledge in the middle of the sky? Finally my wet, feeble grip managed to get the goddamn hole puncher to pierce my bib, and then I ran down that trail as fast as I could to get back down to the protective trees.

The Chicago Tunnel, next to an exposed overlook where we had to punch our bibs in the storm. This photo and next from the ouray100.com gallery.

The view from the Chicago Tunnel, showing Imogene Pass Road, Upper Camp Bird Mine, and the spur of a trail we had climbed—but this was taken on a relatively clear day. When I stood at this point, the sky was dark gray and unleashed a fierce hail and lightning storm. In the distance looms Richmond Pass, to be climbed twice during Miles 21 – 27 and Miles 44 – 50 of the route.

I had gone barely 15 miles and tagged only two peaks, about five hours into this insanely wild and tough event. We had about 87 miles, 12 more peaks and some 40 to 45 hours left to go.

That was one hell of an introduction to the Ouray 100.

The Highest High

Going up Imogene Pass Road, to tag Fort Peabody in Section 4 of the elevation profile, I started to feel giddy and invincible, absolutely reveling in this environment. Drivers in every Jeep that passed gave encouraging remarks or thumbs-up, and instead of feeling annoyed by the 4WD vehicles hogging the narrow road, I waved back at the drivers while savoring memories of my introduction to these mountains, here on Imogene Pass Road, as a kid in the late 1970s and early ’80s. Back then, I’d bounce around in the back of Dad’s truck on a ratty mattress with my siblings (no seat belts, of course), clutching the sides and huddling under a smelly green tarp when the sky unleashed precipitation. I looked over my shoulder to the Chicago Tunnel overlook we had tagged and saw the whole mountainside dusted white with fresh hail. I felt in my element, childlike while reconnecting with family roots and imagining my dad (who passed away in 2013) cheering me on. He would have driven his truck up here to spot me and would have gotten such a kick out of seeing me in this race.

My dad on Imogene Pass Road in the late 1970s, near where we ran to tag the second and third peaks, next to his truck which served as my introduction to these mountains. Nostalgia gripped me during the first part of the Ouray 100.

The Imogene Pass Road climb to Fort Peabody, the high point on the course, pictured in the next photo. These two pics from the ouray100.com gallery.

Fort Peabody, at 13,365 feet, perched on a talus-covered summit.

I punched my bib again and then bombed down from the high point of the course, Fort Peabody (13,365 feet), and met up with another woman, Autumn Isleib, and hung with her to tackle the bogeyman of Richmond Pass together. We paused at an aid station at Mile 21 that looked depleted, even though a relatively small number of runners had passed through ahead of us. I got the last six ounces of ginger ale, and took some potato chips that surprisingly, and disgustingly, were sour cream and onion flavored. “Hmm, slim pickings,” I murmured to Autumn, “and we’re near the front of the pack. Uh-oh.”

After the finish, I’d hear from a back-of-the-pack friend that he dropped after this aid station, because when he arrived, the aid station had run out of water, and he was dehydrated and drenched. At the finish line celebration on Sunday, one of the race officials apologized emotionally for poor planning and thin supplies at this aid station, and he vowed it would never happen again. I chalked it up as a reminder to always carry backup provisions—such as a water filter for refilling at streams, and extra calories—rather than relying on support along the course.

Autumn and I soldiered up Richmond Pass toward the 12,600-foot saddle, along with the uber-experienced ultrarunner Beat Jegerlehner, with whom on any normal day I had no business running near. We picked our way over wobbly basketball-sized rocks in a talus field that would bedevil me many hours later in the dark as we returned this way after nightfall.

I was aware that I was near front-pack runners and pushing my effort level, but the second major storm of the day was darkening the clouds over our shoulders, ominously approaching the mountain we had to traverse.

“We’re gonna beat the storm!” I yelled maniacally to Autumn, “c’mon, let’s do this!” and she looked at me as if I were hollering about beer pong on a Sunday morning. But she gamely followed, although a gap widened between us.

“Be disciplined”—the words of advice from the legendary Scotty Mills, which he sent me in a text message the day prior to the race, rang in my ears. But I rationalized I was being disciplined, because I was pushing to save my life over this exposed pass before another storm unleashed its fury.

The course flags routed us off trail to a technical cross-country section that involved rock scrambling. I spotted my friend Howie Stern way up on the summit, taking photos, and I commanded that he put his camera down and give me a hug, and he obliged. Then I took off, picking my way over rocks and following flags through an extremely tricky section while thunder began once again to roar and rumble like a caged animal.

Cresting the 12,600-foot Richmond Pass, around mile 23 of the Ouray 100, with my new trail friends Beat and Autumn in the background. Photo by Howie Stern.

I crested the saddle and viewed an immense bowl of alpine tundra, as smooth and green as a golf course, unfurled in waves below the summit. The three peaks of the Red Mountains in the distance looked fiery crimson, the late-afternoon light and dark-gray sky saturating their colors. Forked lightning illuminated the sky to the north, each jagged flash immediately followed by a blast of thunder to announce its close proximity. I had maybe 10 minutes before that lightning picked on me.

My Spotify playlist cued up Boston’s More Than a Feeling as the thunder and electricity enlivened the sky, chasing and daring me. In perhaps the most thrilling miles ever in my 25 years as a runner, I ran pell-mell down the mountainside with the cheesy power ballad in my ears, beating this storm and reveling in the drama of the landscape. “This is like The Sound of Music with lightning,” I shouted to one runner I passed, making him flinch with surprise as I zoomed by while he methodically hiked. I reached the protective forest below treeline while sheets of rain started flooding the hillside.

From there I zig-zagged down switchbacks to the aid station where I’d meet my dear friend and crew chief, Clare Abram, and my husband Morgan. Wind-driven rain drenched me, but I didn’t mind, I felt totally prepared and insulated by radiating body heat. I ran strong down the dirt road to the Ironton aid station, mid-afternoon Friday around Mile 27, with Tom Petty’s Runnin’ Down a Dream pulsing in my ears.

As soon as I saw Morgan and Clare, I said wild-eyed, “I may blow up, but those were the best 27 miles of my life.”

Sabrina’s photo of me at the Ironton Aid Station, with Clare bent over getting me food.

Sabrina Stanley, who won the Hardrock 100 the prior weekend, and her boyfriend Avery Collins, past winner of the Ouray 100, greeted me at the aid station with hugs. I reveled in the role reversal of these ultrarunning celebs treating me like a rock star. Sabrina took my photo and said, “Way to go, you’re first woman!”

“Well, that’s irrelevant,” I shot back dismissively or defensively, because I didn’t want being in the lead to affect my head or my pacing. But of course it did, of course I wanted to hang onto that lead.

The Lowest Low

About 13.5 hours and 31 miles later (which translates to a 26-minute/mile average pace for those 31 miles—yes, the going really is that slow), I stumbled into the Weehawken Aid Station, Mile 58, around daybreak, a completely different person.

“Must nap, 15 minutes,” I mumbled to my friend and pacer Allison Snyder, and without thought I lay down and lost consciousness on the aid station’s pile of drop bags, cold air seeping through a poncho and chilling my bones. I was out as quickly as if anesthetized.

Glamor shot, Mile 58, daybreak Saturday morning.

I had in my head that the past five miles of the Weehawken segment would be the easiest on the course, ascending only to about 11,000 feet, and plus, I’d have Allison accompanying me beginning at Mile 53. I had done this segment during a training run, no big deal. Even the name “Wee-hawken” sounds cute. But I began to unravel on that Weehawken out-and-back. Coming back into the aid station, powerless to resist a nap, I felt shocked and numb, disbelieving how quickly my race had devolved and left me trashed.

Earlier, I had nailed Miles 27 to 53. All my logistical planning and gear prep paid off; Clare had what she needed, such as several layers of fresh clothing and dry jackets, to take care of me and feed me at the Ironton Aid Station (which runners pass through three times). I had steadily ticked off the 16 miles on the double loop known as Corkscrew Gulch, between Miles 27 – 43, sharing several hours with a jovial fellow from San Diego, Eric Makovsky, who took nearly 50 hours last year to finish the Ouray 100 and felt stoked to shave several hours off his time this year. A pediatric nurse and professional singer, he had an effervescent spirit that kept me humming along past nightfall.

I approached the 12,600-foot Richmond Pass close to midnight and solo (Miles 43 – 49), and still felt relatively strong. Ascending Richmond Pass felt monumental, harder than any pass I’d experienced while pacing the Hardrock 100—even the 14’er Handies—and descending proved no easier, due to the cross-country section that involved rock scrambling with eyes straining to spot the next flag in the dark distance; and the chunky, sharp, unstable rock footing on the decline, whose crevices threatened to grab and snap my trekking poles. At least a full moon rising in a clear sky enhanced the lighting and views.

I thought about a text that iRunFar’s Meghan Hicks sent me a day earlier, wishing me luck and fortifying my resolve. Meghan, a Hardrock 100 and Tor Des Geants finisher, hasn’t done the Ouray 100 but knows it from pacing her friend Melissa Beaury, who holds the women’s record in 34:26. Meghan had noted how the Ouray 100 messes with runners psychologically—the severe weather, the out-and-back sections with repeat visits to the same aid stations, and most of all, the interminable vertical gain and loss.

“You always have to climb at least 3K and descend at least 3K. Don’t even think about it, just do it,” Meghan typed to me. I was just doing it, but I was thinking about it, too, thinking especially about all the mountain passes in the second 50 miles that I’d have to spend another 24 hours going up and down.

Then I met my friend and pacer Allison at Mile 53, sometime around 2:30 a.m., and several bad things started to happen. These bad things began to mix and flow together, gaining power like a cascade.

In hindsight, I experienced the first “uh-oh” signals on the hard Richmond Pass return climb, but I pushed them away until they demanded attention on Weehawken. In no particular order, the bad things involved:

- A pulse in my ears that sounded like a heartbeat in my throbbing head.

- A gunk in my lungs that fluttered and burned with each deep breath.

- A gag reflex that rebelled against swallowing anything, even gels.

- A swelling in my shins and ankles that restricted the ability to flex my feet, making my lower legs feel stumpy and clumsy.

- And perhaps worse, a blend of discouragement, frustration and self-pity. These emotions fomented a mental storm that doused optimism. I blamed it partly on the trail friends with whom I’d chatted amicably hours earlier—first Beat, then Eric, then two women named Sunny and Esa, followed by Autumn—all passing me while seeming and acting like their determined, positive selves. I recognized it wasn’t their fault, it was all mine, which only made me feel worse.

When I started the Weehawken climb with Allison, she did her best to revive my spirits, but she couldn’t improve my oxygen intake. I couldn’t catch my breath; even at this snail’s pace, I breathed heavily and rapidly as if recovering from a sprint. I tried a pattern of counting 20 steps, then pausing to lean on my trekking poles and breathe deeply for 10 breaths. But that didn’t help. I took a few hits off my new Albuterol inhaler, which I got in June following respiratory issues at the San Juan Solstice 50, and it provided short-lived relief. My lungs were telling me—through coughing, burning and rapid breathing—that I had stressed them out by working so hard in such thin air for the first 50 miles.

Without adequate oxygen flowing through my blood, my gut started to shut down, my muscles strained to do their job and my brain became more foggy. The only way I could respond was by slowing down considerably so that I would need less oxygen. So I started moving like a geriatric hiker at about a 35-minute/mile pace, with lots of short breaks, and consequently, cold and stiffness numbed my limbs. The desire to sleep trumped the desire to catch up to those who had passed me.

Giving Up, or Giving My All?

Allison woke me up after the 15 minutes I spent passed out on the drop bag pile at the Weekhawken Aid Station. Almost immediately, I started shivering. My eyes took in the site of Vale Hirt, a perky, small-statured, big-hearted woman who was attempting the Ouray 100 after two prior DNFs. She had been way behind me, and now here she was, staggering and telling her pacer she needed to sleep.

I summoned all my strength to form words and speak authoritatively from my prone position in the dirt, “Do not lie down, Vale. It’s not worth it. You’ll feel worse.” She nodded, acknowledging the wisdom of this old lady in the trash heap, and slumped miserably in a chair instead.

I thought to myself, She really cares about this race. I’m not her.

I closed my eyes again and visualized the mountain passes and peaks we faced in the next 42 miles: Hayden Pass, summiting around 12,000 feet up, out and back again; Twin Peaks, up to nearly 11,000 feet, climbing rotten, loose wooden steps falling out of the eroding mountainside; Chief Ouray Mine, up and down another zigzag of switchbacks up another 3000-plus feet; and then the final 11-mile ascent way above tree line, up more swaths of switchbacks on a talus field, to the so-called Bridge of Heaven.

I had done all of those segments in training runs, to prepare for this moment. But those careful, arduous training runs on those segments dissuaded me now. I had seen them in daylight already; I knew what to expect. And every part of me did not want to see or do them again. I wanted to avoid them from the comfort of my condo; I wanted to call it a day at 24 hours.

I sat up and told Allison, “Do you have any coverage here? I’m going to call Morgan. I just can’t face the remaining passes like I’m feeling, at this pace.” I asked for her phone and took my tracking device out of my pack to hand to the aid station official.

Allison looked at me sympathetically and said something philosophical such as, “You know yourself best.”

I called Morgan, who was a few miles away at our condo rental in Ouray, at around 6 a.m. “I’m dropping, I need to.”

He didn’t need an explanation. Sounding chipper and relieved, he said, “No problem! It’s OK, I’ll be right there.”

I huddled on the ground, miserable, shivering uncontrollably. Vale got ready to leave and urged me to follow her. I shook my head, saying, “I’m done.”

Meanwhile, back at the condo, Clare was supposed to be sleeping in because she planned to start pacing a mutual friend in about 12 hours. She expected Morgan to leave the condo to meet me at the next aid station several hours later. She woke up confused and told my husband, “It’s too early for you to leave,” and he explained that he was going to get me.

“Oh no, no,” said Clare, jumping out of bed, a woman always on a mission.

About 10 minutes later, I saw our truck drive up, and I spotted Clare next to Morgan. I told the aid station official—to whom I was on the verge of handing my tracking device, but I just couldn’t unleash my grip—”Oh, fuck, here comes the good-cop, bad-cop.”

Clare marched up, all business, no bullshit sympathy, and in her prim British accent announced, “Oh, no. No. I do not see a bone, I do not see blood.”

She pulled a folded piece of paper out of the pocket of her down puffy, the memo I had printed out for her as my crew chief. She unfolded it and pointed defiantly to a paragraph I had typed a week earlier. “It says right here, right here!” she jabbed the paper for emphasis, “that I am not to let you drop unless you have a bone sticking out or you’re bleeding.”

I looked at Morgan, who half-shrugged and cowered next to Clare. He was not going to save me. And then I burst into tears, shoulder-wracking sobs. Clare, the person who had paced me to a sub-22 finish in my first 100-miler, and a sub-24 finish at the storied Western States 100, was not going to let me off easily, was not going to let me down. Her determination and loyalty wrenched my heart and made me feel like more of a loser, and I cried harder.

Clare kneeled down, put her arm around my shoulders, and said, “I’ve been there. Do not think about all the miles left. All that matters is getting you to the next aid station. Let’s get some food in you.”

I sobbed and shivered. Allison and Morgan stood back, looking uncertain, deferring to Clare, the Captain Sully about to land a crashing airplane.

Clare barked orders to get the sleeping bag, get some ramen. I saw another woman who had been way behind me, Tina Ure, the multi-Hardrock finisher, come into the aid station and look at me as if, “I’m glad that’s not me,” and I sobbed harder. All the pent-up congestion in my sinus passages and lungs gushed through my nostrils and mouth, making me gag and cry more as Allison—in her first ever gig as a pacer, probably wondering what she had signed up for—fished a wad of toilet paper out of my pack.

The cocoon of a sleeping bag, and a hot bowl of ramen, made the shivering subside. Clare told me, “You’re going to get to Crystal Lake,” the next aid station about eight miles away, over a 12,000-foot pass. It was an order, not a question, and I nodded sheepishly. I tucked my tracker back in my hydration pack’s pocket.

Clare pulled me up and steadied me on wobbly feet. I started moving down Camp Bird Road, toward the next trail head, on autopilot, still crying, my hydration pack hanging off my shoulders not properly attached, my trekking poles scraping the dirt while dangling from straps on my wrists and dragging uselessly, Allison scrambling in the background to get ready and follow me, all the litter and layers of clothing I had shed left behind on the ground for Clare and Morgan to clean up. I fumbled to put earbuds, attached to my old iPod Shuffle, into my ears and to tune out everyone and everything except the music. Shuffling, sort-of jogging, I advanced to the next trail head.

I so very much wish this story took a turn toward a happy ending here. I so very much wish Clare had been right when she promised me I’d feel better with the sun rising in the fresh new day.

But I felt even worse on these next miles, crossing the 100-kilometer mark. The breathlessness, weakness and gag reflex returned. On the steepest section, I paused to take so many breaks that it took about 40 minutes to go one mile.

When we finally summited Hayden Pass and began traversing and descending, I tried to regain a positive mindset by noticing how I breathed more normally on the downhills. But I couldn’t bust up the pity party. As soon as we started going downhill, I felt miserable and sorry for myself because my lower body lost its functionality and my feet forgot their agility. The swelling and numbness in ankles and shins spread upward to knees and thighs. I felt as if I had the after-effects of an epidural, unable to control my legs. I used my trekking poles as if they were crutches, relying on them for balance as I slipped and tripped repeatedly.

Allison’s photo of me from Saturday mid-morning, approximately 26 or 27 hours into the event, as we summited Hayden Pass.

I felt utterly debilitated and miserable. I kept dwelling on how I want to be a strong runner who covers 100 miles in 24 hours, not a slow, weak hiker who takes twice as long on a course like this. No part of me wanted to spend the next 24 hours traversing the remaining mountain passes in this manner. My body felt so foreign and messed up, I worried I was crossing over from mere suffering to inflicting long-term damage (likely not the case, but the possibility messed with my head at the time).

The steady train of runners ahead of me—the peer group I should have been running alongside; Beat, Sunny, Esa, Eric, Autumn and others—passed me one by one on their return from the next aid station, steadily hiking back up the mountain above tree line while I struggled to crutch and stumble down the trail, a couple of hours behind them. I decided, and felt certain, I would inform my crew at the next stop that I’m dropping, and not let them talk me out of it. I stopped caring about finishing. I only cared about avoiding the climb back up this mountain after the turnaround at the aid station.

The hardest thing would be facing the faces of my crew, not just Clare, but also John Medinger and Lisa Henson. John and Lisa, the ultrarunning legends who had been waiting for hours at an aid station for my arrival so that Lisa could pace me the final 25 miles. I was so looking forward to spending 25 miles with Lisa.

They cheered my arrival as if it didn’t matter I was several hours behind my timeline. Seeing their energy, their support, their care and enthusiasm made me start crying again, from guilt and defeat. Because I had made up my mind and was letting them down.

Clare started her “No, no,” dialogue as if quitting were not an option, but I said, “You can’t talk me out of it this time. Please don’t. I can’t go back up that mountain, and even if I could, I couldn’t get down the other side. I won’t.”

They tried so hard not to listen to me and to act as if I just needed rest and sustenance in order to get back on the trail.

The fact that part of me knew they were right just made me cry harder and feel like more of a failure. (I have never bawled like this in public, except briefly at the finish line of the 2014 Miwok 100K. I couldn’t control the pathetic, cathartic tears, which released all my pain and disappointment.)

I objectively knew I had enough hours before cutoffs to keep going and make it to the finish, even at this ridiculous glacial pace of 30 to 40 minutes per mile. But I couldn’t summon any desire. I was too miserable, too doubtful of my ability to handle the remaining downhills on Gumby-like legs. I wanted to get off the trail and end the suffering more than I wanted to finish, and I didn’t see a way to turn around those feelings.

Lisa, John, Morgan and even Clare finally gave in. They let me hand my tracking device to the aid station official, and they helped me to our truck. I felt enormously grateful and relieved, letting go of my cares and, finally, letting myself truly rest.

About an hour later, as I took care of my aged, depleted body in our condo, I heard thunder and looked out the window to witness another extreme storm. A friend took the picture below on Highway 550, not far from the Crystal Lake Aid Station where I dropped out. This is the storm that I would have hiked through on the return trip over Hayden Pass if I kept going—the storm that Vale, Tina and others in the back half of the pack bravely suffered through on the mountain ridge. During the storm, I felt relieved and grateful I wasn’t with them on the mountain anymore.

The Saturday afternoon downpour during the Ouray 100, as seen from Highway 550, next the mountain pass where I dropped out.

The Day After

I spent the next 24 hours, from midday Saturday until the final cutoff time for the event at noon on Sunday, napping and feeling mostly relieved. Also, I became happily distracted by crewing for my friend and client Tara, who ran the event’s 50-mile division throughout the night while Clare paced her in the final 25 miles.

It wasn’t until about 12:30 p.m. on Sunday, as we all gathered for the finishing ceremony at the Ouray Hot Springs park, that regret predictably and painfully began dominating my emotions.

I saw the faces of Sunny, Esa, Autumn, Vale, Tina and others who had finished. Sunny, the first place woman, took 44 hours, 46 minutes; Tina, the final female finisher, took 50 hours, 50 minutes. I felt such admiration for them—I wanted to be them.

Of the 81 100-mile starters (19 female, 62 male), 31 finished (8 female, 23 male), a 38% finish rate.

I believe I could have been finisher number 32. I know readers of this story will conclude that I went out too fast or pushed too hard in the beginning. I disagree, I think I simply did my best and made the most of the first quarter of the route, and I wouldn’t want to temper the emotional high of that first day. The problem is, I didn’t want the finish badly enough, and my ego stood in the way of making peace with falling so far behind. I never had my head or heart fully committed to suffering and enduring through the second day and second night. Well-wishers via Facebook sent messages telling me, “You gave it your all,” but I don’t think so. I suffered mightily, but I gave up before giving it my all.

I feel chagrined by my second-ever DNF, this one so much harder than the first because I invested so much time and training in the Ouray 100. I’m confronting the reality that I did not fulfill my hopes or live up to my expectations, and I wonder whether I have it in me to personify the “wild & tough” Hardrock motto. And yet, I’m not sure I want it enough to finish it, even after experiencing this disappointment. I don’t know if I can bring myself to sign up again for some 48 hours of miserable slow hiking in extreme conditions, given how I felt at the 24 hour mark. Part of me wants to sign up for the 50-miler and see how well I can do at that distance.

For now, I will hold off any decisions about signing up again next year. I’ll savor those magical first 27 miles, the friendship and support of my crew and other trail friends, the haunting beauty and power of those mountains, and especially, the experience of 66 miles in one of North America’s hardest 100-milers that athletically and psychologically took me to the zenith and nadir of mountain running.

Cheers and thank you, Clare, for making me get to Mile 66!

Yikes. I know it must be a beautiful course, but that sounded miserable. For what it’s worth, I think you made the right call. You have already proven yourself many times over as a badass ultra runner. When it’s no longer enjoyable and potentially dangerous, what’s the point? I think you run to enjoy the natural beauty around you and connect with like minded folks (though you clearly also like to suffer). You took on an incredible challenge and gave it what you had on the day. There will be many more great adventures. I am proud of your effort and for sharing your honest story. Enjoy your summer with your family and animals in Telluride this summer😀

ABSOLUTELY BEAUTIFULLY & FANTASTICALLY SAID!!! SARAH!! YOU ARE SOOOOO PHENOMENALLY AMAZING -AS A PERSON-AS A RUNNER-AS A WRITER-AS A MOM-AS A WIFE-EVERYTHING!! INCREDIBLY WRITTEN PIECE FROM AN INCREDIBLY EPIC EFFORT IN AN INCREDIBLY EPIC RACE!! I’m sorry I wasn’t there to be able to cheer you on & hug you & help in any way!! CHEERS -YOU AMAZING HUMAN!! 💥❤️💥

Isn’t life beautiful, the highs and the lows? Our consciousness? Our ability to test the potential of the human spirit? Even in the heartbreak, their is wisdom. What did the mountains teach you that day? It sounds like quite a bit. And Sarah Lavender Smith- you are still a badass, regardless of the outcome of a 100 miler. (Last, I have to add, what I feel is more important is that with your book, you have/are inspiring hundreds of others to go after their dreams, explore their own freedom, and test their own potential…the world needs that.)

Well said