I look out the window of our trailer, parked next to the construction site where we’re building a home on 35 undeveloped acres six miles outside of Telluride, Colorado, and I marvel at the odd juxtaposition of old and new objects we’ve created and collected in the past couple of summers living here, now scattered around a homesite taking shape.

This is how our property looked when we arrived on May 7, showing earth-moving equipment prepping the homesite for the foundation; our Airstream and barn stand on the edge of the construction zone in the background. The stripes of snow on the mountains melted by mid-May.

Our Airstream, where we daily experience “tiny house living,” is flanked by flatbed trucks loaded with materials, earth-moving equipment, mounds of dirt, rows of trenches, our dusty Subaru wagon and GMC truck, our ATV, the barn we built last summer and its two horses, and our son’s skateboard ramp—and in the center of it all, a rectangular concrete home foundation where workers are starting to install the floor joists.

At the turn in the driveway, a historic yet high-tech outhouse stands next to an industrial porta-potty, awkwardly stuck side by side like family members from different generations. We moved the outhouse from lower on our property, where it had sat next to an old barn for the better part of the 20th century, and outfitted it with water filtration equipment and telecommunications gizmos we need to live here (the kind of stuff that will go in our basement utility room when the house is ready). A few weeks ago, we topped the outhouse with a satellite dish in a seemingly never-ending and expensive quest to secure reliable Internet service—and it worked great for about a week, until new leaves on the surrounding aspen trees grew in, and the seasonal leafy green blocked the signal. So we moved the satellite dish last week to another side of the property, creating yet another strand of electrical cords and hoses that crisscross the land to support a funky temporary infrastructure while the house gets built.

This pretty well captures the strange hodgepodge of old and new we’ve accumulated on our property, and the make-do temporary infrastructure installed until the house gets built.

Down the hill a little ways sits the tilting, falling-apart barn from the 1930s that we’ve propped up with support beams and hope to restore someday. The barn acts as a quiet reminder of the ranchers who made a living on this land before us, and it warns us to build with care, or the mountain weather and passage of time will work together to wear away our new house just as the natural forces corroded the barn in decades past.

The beloved, rickety old barn on the lower part of our property, with Wilson Peak in the background. (We took this photo last autumn, following an early dusting of snow; sadly, Wilson Peak has hardly any snow on it this season due to the light winter and drought conditions.)

About six weeks have passed since we transitioned from our Bay Area home to here, where three years ago we decided to leverage our resources to purchase this place and build a home. It’s not intended to be a luxury second home for vacations, like the monstrous big-log homes that sit vacant most of the year in the ski village. We intend to live here half the year, May through October (if we can make two-state living work financially and logistically, which is still an “if”), perhaps year round after retirement. It’s our desire and midlife project to stake a claim in this particular corner of Colorado, which always made us happy and felt like home, by constructing a farmhouse-style two-story house. In the process, we’re building on my family heritage and creating something for our kids’ future.

We spent the past two summers living in the Airstream and a canvas tent annex to plan the home, and now the construction is really happening. I periodically ponder, What are we doing—and can we do it? How’s this going to work out? Those questions arise as I survey the scene where we’ve turned a swath of the natural, untouched pastureland into plowed dirt, using equipment to modify the slope of the hillside and to level the homesite; or, when Morgan and I make another wire transfer in the five or six figures to finance our construction, carefully forecasting and managing the debt.

We’re investing all our resources and energy to build our future here. I wonder, are we over-building? Under-building? Should we have planned something more affordable, less custom but comfortable, like my dad did when he built his cabin across the road four decades ago? Did we make the right decision earlier in the year to spend a small fortune on century-old reclaimed wood from Canada and get it shipped all the way here for hand-hewn support beams? And did we make the right decision a few weeks ago to indefinitely delay building a detached garage for the sake of saving money? Yes, I reassure myself, those were smart decisions. I’ll go crazy if I keep second-guessing all the life-altering and costly decisions with which we’ll live for decades to come.

What I know for sure is: I love this land, I feel connected to it, and I feel an enormous responsibility to build on it in a way that respects and honors the land’s history and its natural setting—and also, in a way that doesn’t bankrupt us or saddle us with design decisions we’ll regret.

The worksite in early May, at the start of building forms for the concrete foundation.

One month later, the foundation is done and the floor is going in.

One of three truckloads of century-old, hand-hewn lumber reclaimed from farmhouses in Canada that we purchased and shipped here to southwestern Colorado for use in our house. The lumber now sits in nearby Ridgeway at a sawmill, worked on by a team led by Erik Bodie Johansson, whose Instagram account is pictured below. He and his crew are crafting the lumber into beams for our house; when the time is right, the wood structures will be taken apart, transported to our property and installed in the house. It’s been exciting to follow his documentation of the wood that will form the bones of our house.

An architectural rendering that gives a rough idea of the two-story, three-bedroom farmhouse-style home we’re planning.

We couldn’t do this without our builder, Justin Stratman, and his crew. Justin is devoting himself entirely to our project this season, and he sweats every detail to make our house as special and well-built as possible. The other day, for example, he showed us some rusted old drilling rods reclaimed from some salvage yard or industrial site nearby, which he picked up because he thought they might look cool integrated into our stairway railing. Yes, we agreed, go for it!

I thought it would bother me to have so many workers show up by 8 a.m. every weekday morning, right outside our trailer’s doorway; but now, as their faces grow familiar, I welcome the crew showing up to make progress, and the reassuring sight of Justin overseeing it all.

Justin and Morgan reviewing plans outside the Airstream as Beso looks on. The blocks of wood in the background are samples of the wood we’ll use for our house.

Family Roots and Branches

Our parcel sits at 9,000 feet elevation on Last Dollar Road on Deep Creek Mesa, an area about a mile from Telluride’s small airport, where mountains cradle rolling pastureland and Deep Creek carves a canyon that connects with Highway 145 in between Telluride and the village of Sawpit.

As friends know, this place molded my sense of identity and adventure when I was a kid. My dad purchased five acres, across the road from what’s now our parcel, in the early 1970s, where I spent every summer of childhood. The land that we now own felt like an extended, wild playground where I’d climb around the aspen groves, play house in that historic barn, and catch and ride horses belonging to the Aldasoro ranching family, who periodically kept their pack of horses here.

“Last Dollar” and “Deep Creek”—the two phrases that name our road and the nearby river make me think of my parents, and laugh, because in the 1970s, when my parents were in their early 40s, we got CB radios for Dad’s Chevy truck and Mom’s Datsun wagon. Dad made “Last Dollar” his CB handle, which fit due to his fondness for gambling at poker and other games, and Mom chose “Deep Creek” because it played to my dad’s raunchy sense of humor.

My grandfather on my dad’s side, the author and historian David S. Lavender, was born and raised in Telluride and passed onto Dad a connection to this region and a desire to live here part of the year. (Dad’s work for The Thacher School, where Grandpa taught English for three decades, meant that I grew up mainly in Ojai, California, and went to Thacher for high school, but Dad had summers off and consequently we lived in Telluride during summers.)

My dad, whose ham-handed design sensibility veered toward utilitarian and had little to do with aesthetics, didn’t go through the arduous, detail-oriented process of designing a home like we’re doing now. He stretched his resources to buy the five acres, then simply bought an affordable Lincoln log-style kit and erected the cabin in 1975 when I was 6. I vaguely remember that rowdy summer when Dad hired local hippies with negligible construction experience to put up the cabin, and I made forts with scrap lumber.

Summer of ’75 when my mom (pictured on the right) and dad (third from left) built their cabin from scratch from a kit. My brother David, second from left, lives there now. That’s me second from right, and my sister Martha on the left end.

I more vividly recall the hours I spent exploring the open meadows and aspen groves on the property we now own, across from Dad’s cabin, on the lookout for sheep or cow skulls to inspect and collect. One time, when I was about 7 and barefoot, I was walking down toward the old barn and nearly put my foot on the back of a porcupine whose quills rolled side to side as the porcupine trundled along. I screamed so loudly, my mother heard me from inside the cabin up the hill, and she came running and hollering with fear that I had fallen into an abandoned well.

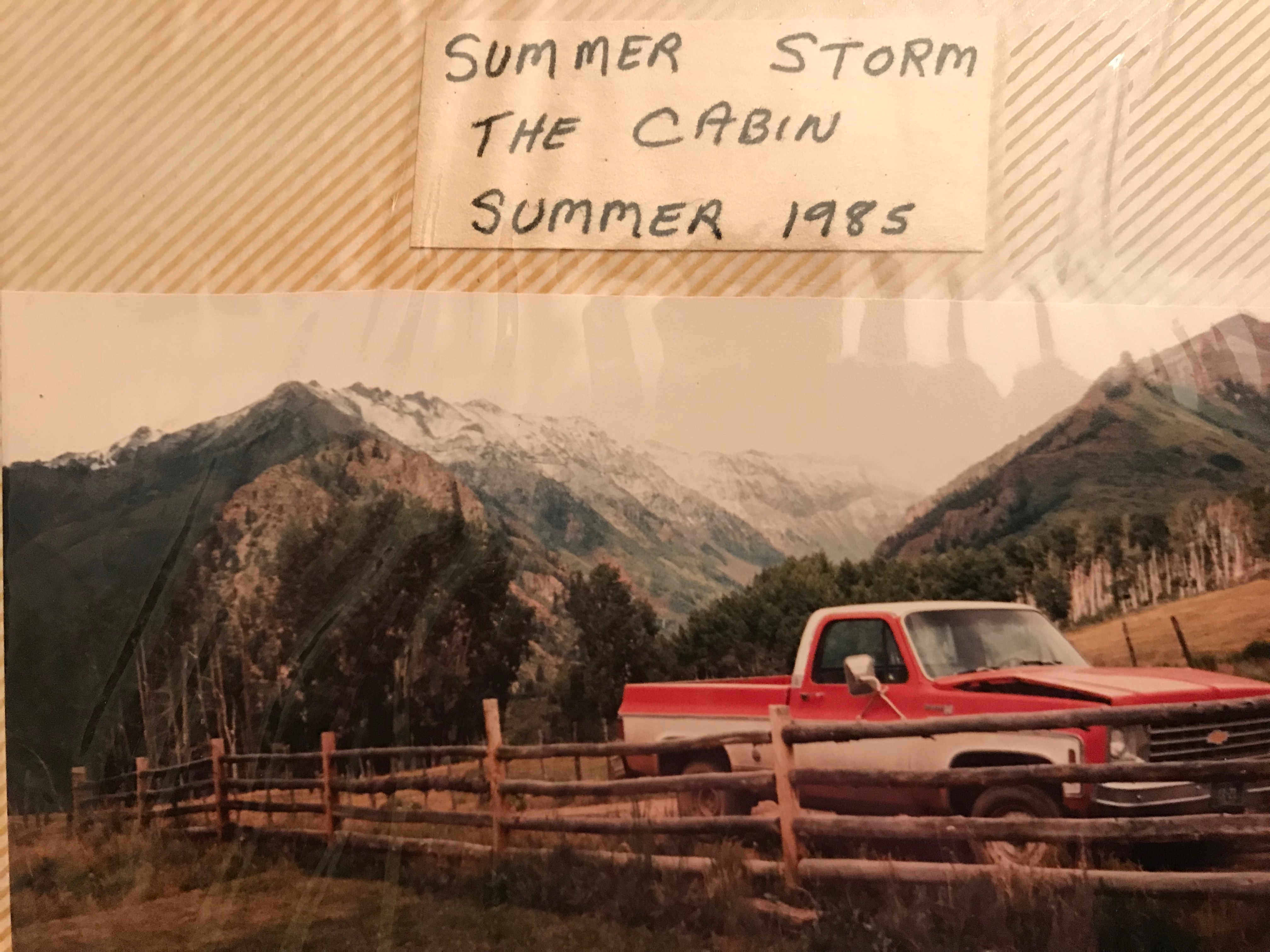

A snapshot from my parents’ weathered photo album shows Dad’s beat-up truck, nicknamed “Big Red,” parked in front of our family cabin on Last Dollar Road; behind the truck, at the corner of the fence line on the left side, is the entrance to the driveway of the property Morgan and I purchased three years ago. The land up the hill to the right is protected national forest land, where the Deep Creek Trail starts. My brother and sister-in-law now live here.

My dad, who passed away in 2013, is seen here in 2003 with my kids, then age 2 and 5, on the parcel of land that we bought across from his cabin. The real estate rep who put this parcel on the market in the early 2000s built this “viewing table” where our family would picnic and take walks. We couldn’t imagine then that we’d be building a house 15 years later directly behind the table.

And here’s a view of the same picnic table from last week, when we shared dinner with my brother David and sister-in-law Karen. The construction site and work trailers surround the homesite in the background, and behind them stands the barn we built last summer.

Ditching It

Grandpa’s grandpa, Charles Painter, arrived in San Miguel Valley in 1880 and was the first mayor of Telluride and the town’s newspaper publisher. (My grandpa was born with the last name Painter, but then his mother divorced his father, David Painter, and remarried rancher Ed Lavender, hence our Lavender name.) Property records show my great-great-grandfather briefly owned about half our parcel’s acreage. A leading businessman who likely always was on the lookout for a quick profit, he bought the land as a tax lien in 1907 for a mere $100 and sold it a year later for ten times as much.

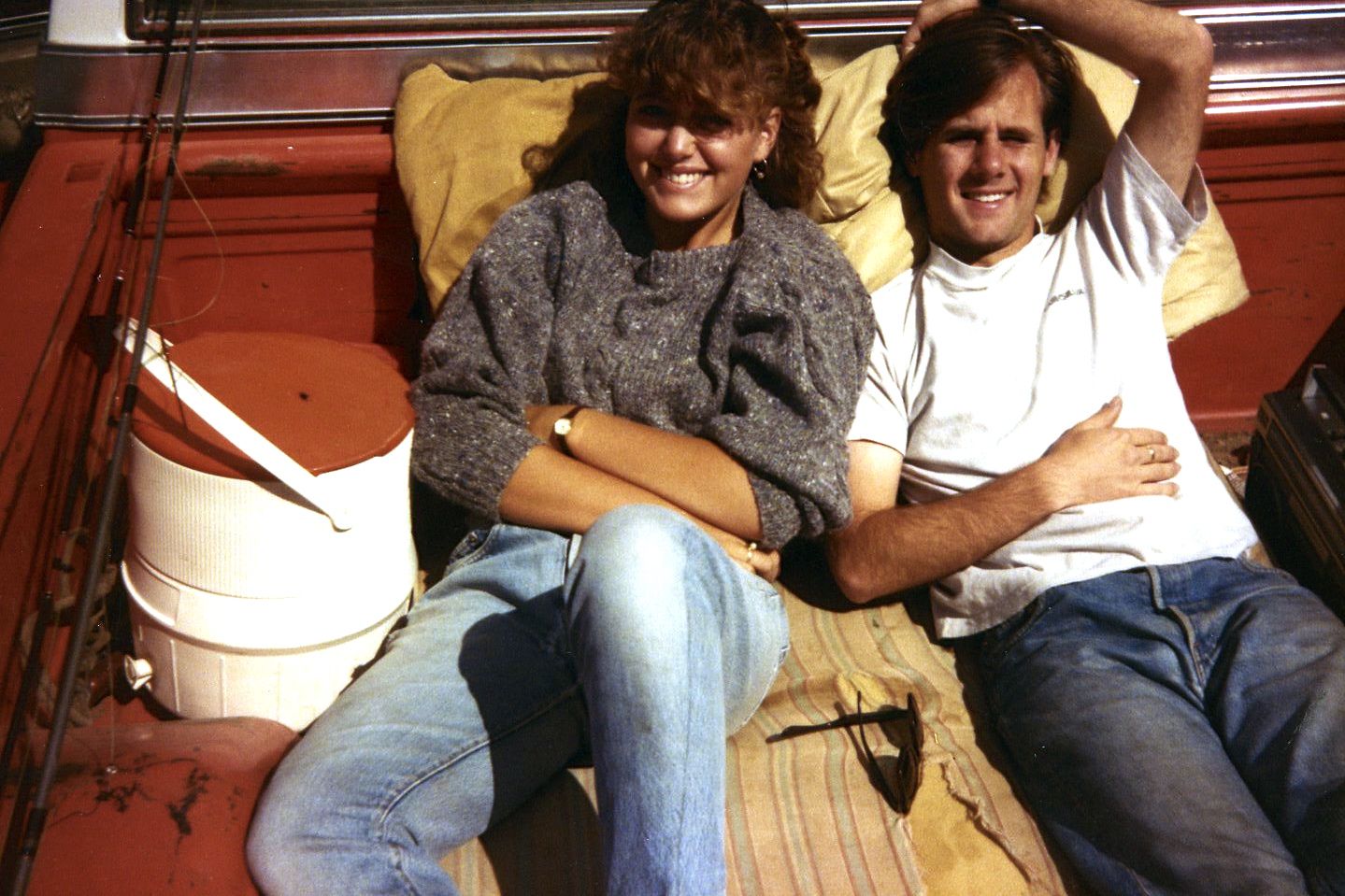

My husband Morgan—who fell in love with Telluride and my dad’s cabin in the summer of ’85 when he was my boyfriend, the first of many summer trips he took to spend time with my family and me here—discovered that bit about my ancestor briefly owning our property when Morgan delved into the property’s title history and its water rights as we embarked on making a bid to buy the land.

Morgan and me in the summer of ’85, in the back of Dad’s truck, heading off to fish.

We knew we couldn’t bank on living here for the rest of our lives, and pass it on to our kids, without a reliable source of water here in the arid West; one need only look at the meager runoff from the thin snowpack, or to feel the dusty, furnace-like afternoon wind against chapped skin, to understand that climate change and drought seriously threaten the long-term viability of life here. So Morgan learned all he could about the land’s lifeblood, its aquifer, which thankfully measures a robust flow, and he negotiated hard to drill a dedicated well next to our homesite two years ago. The real estate reps who are still trying to sell neighboring parcels wanted us to agree to share a well with neighbors. Nope, no dedicated well of our own, no deal.

Morgan also studied the history and rights to the irrigation ditches that branch out and flow like veins around our parcel. A three-tiered system of ditches on the hillsides above us divert precious snowmelt from Sheep Creek and Deep Creek, two tributaries to the San Miguel, the big river that flows from Telluride down valley. First built in the late nineteenth century, these ditches are testaments to the collaboration of ranchers who worked together to build and clear them. Several times a week, I run the trails that border these simple yet ingenious ditches—because they provide one of the few flat, relatively smooth places to run around here—and pay homage to their history and engineering. By controlling the flow with rudimentary hunks of metal placed near the stream, and then cutting notches into the ditches to allow the water to flow downhill, the property owners irrigate different parts of their land.

Morgan regularly inspects and clears our ditch, seen here last autumn. It runs on the uphill southeast side of our property through an aspen grove.

“Here’s your Christmas present—I bought us a ditch,” Morgan told me in December of 2015, before we had even closed on the property. When he recognized the value of rights to the ditch and to a percentage of the water that flows from the stream, he purchased a claim to it for about the price of a small car. I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, but now I do. Water is gold. The right to this water historically is based on seniority, however, so if—or more likely in this drought, when—the water resource managers make a call that more water needs to flow undiverted to the San Miguel River, then we may need to temporarily give up our claim to the stream flow and let the ditch run dry.

I’ve savored watching Morgan ditch his regular life as a Bay Area attorney, start a new firm (specializing in litigation graphics, leveraging his creative talent), and use his newfound flexibility to work this land. He still works full days, sitting for hours at the table in the Airstream to manage his work remotely; but when he needs a break, he usually heads into the aspens to check and tinker with the ditch. Over these past two summers, he developed a hobby of managing and improving our ditch for the sake of green pastureland where horses can graze, along with sheep herds that periodically pass through and wild elk herds that visit nearly every week. Unfortunately, Morgan suffered an accident three weeks ago that ruptured his Achilles, so with his mobility restricted, he gets out to manage the ditch on an ATV.

Morgan, wearing a soft cast so his Achilles can heal, adjusts our ditch flow to irrigate the meadow.

The Daily Chores

With Morgan’s mobility restricted for eight weeks until his Achilles heals, the animal care falls on me (with some help from our 17-year-old son, Kyle). A large portion of my day revolves around caring for two horses, a dog (plus my brother’s two dogs, whom we’re dogsitting while he and his wife travel) and a frisky kitten. We adopted the kitten a few weeks ago to manage the rodent population, after we reopened our Airstream in early May and discovered mounds of turds from mice that infested the trailer over winter. The kitten is adorable, except when he pees on our bed.

We started with just our Portuguese Water Dog, named Beso, who adapted to Colorado life once he bonded with my brother’s two dogs across the road. The three dogs blissfully roam back and forth between the homes, gnawing on elk bones, diving into the ditch water, and tracking mud into the my brother’s cabin and our trailer.

Then our kids, Colly and Kyle, twisted our arms to get a family horse two summers ago. They didn’t have to twist hard. Both Morgan and I ride and love horses, since we both attended Thacher School (where we met) and rode in the school’s horse program. Then Colly and Kyle attended school there and became horse-crazy accomplished riders. So Cobalt the quarter horse came into our lives. But Cobalt needed a place to live, plus a friend (because horses are herd animals and shouldn’t be alone), so last summer we built a barn for Cobalt and started boarding a neighbor’s horse for companionship.

The two-story barn stands to the east of the homesite, a reassuring reminder that we actually can plan and complete projects. The masonry base, the rough lumber sides made of reclaimed wood and the metal roof prefigure the style of the house we’re building. Every morning I slide the thick wooden barn door to the side, step into the central area that’s filled with hay, look to the tack room filled with saddles and tools, and look up at the storage loft that serves as my son’s makeshift bedroom, and I feel grateful that horses came back into my life and that we built this barn as a warmup to building the house.

Our Airstream parked next to the barn we built last summer, taken last October when the aspens turned golden.

But horses mean dirt and manure, and a daily need to feed, exercise and clean them. So I’ve rekindled the main chore of my youth, of mucking out manure from a paddock, tossing alfalfa to hungry horses, and nurturing a relationship with our steed as I exercise him almost daily. I try to ride most days, or to lead the horse up the switchbacks of the Deep Creek Trail as I get my exercise running and hiking by his side; but some days, we simply turn Cobalt and his companion, named Freckles, loose in a pasture area fenced with electrical fencing that we can move around to prevent overgrazing of any one area. Our small mountain of manure dumped in a corner of the aspen grove grows daily, and we’re planning to build a three-bin composting system—one of several projects on the summer to-do list.

Riding Cobalt, with Wilson Peak in the background. This is a flat area on our property that where we intend to install a fence and improve the footing to create a real riding arena.

Because of the horse care, plus the dusty land around us and the cumbersome process of taking a shower in the Airstream, I’ve never been so dirty. Within one week of living here, my thumb became so permanently chapped, cracked and soiled that my iPhone no longer recognized my thumbprint for Touch ID. I live with dirt; I try to wash it from the cracks in my dry skin or to get it out from under my nails, but it seems a lost cause at this point. I put on the same dusty work pants every time I go to the barn. I sweep and dust the trailer daily, but the dog and the two guys I live with track more dirt in, and the wind blows dust through the screen door. When we celebrate the occasional rainstorm, as we did last weekend, we witness with a mix of delight and horror as the thick dust turns to deep mud. Suddenly, mud covers the floor, the sides of the vehicles, the horses who roll happily in it—mud gets everywhere. I’m gradually making peace with all this dirt and accepting it as a fact of life.

This is how my hand normally looks now. Sometimes during the day, it’s much dirtier.

Sometimes I wonder why I can’t get more “real work” done—why I’m not writing or reading more, or why I’m not taking on more coaching clients. I wonder if I should get a real job with regular hours to bring in more income. But I barely have enough time to take care of my current stable of clients, plus devote enough hours to training to prepare for two mountain ultras on the calendar. I spend about half my day taking care of clients and running, and the rest of the time goes to chores that revolve around animal care, homemaking and house planning.

Where does the time go? Every mundane aspect of home life takes a little longer and is a little more complicated than usual. To bathe, we have to empty out the Airstream’s extra-narrow shower, because it doubles as a storage closet that holds the dog food bin, broom and mop. To get dressed, we have to paw through clothes stored in a large plastic bin under the bed, because the trailer doesn’t have room for a real dresser with drawers. To pour a glass of drinking water, we have to refill the plastic water jug from the water filtration system housed in the old outhouse. To cook dinner, we have to manually light the stove with matches (making sure the propane tank outside isn’t running empty), and then time the cooking to heat the pots and pans in shifts, because the three-burner tiny stove can barely handle more than one pot at a time.

To flush the toilet, we have to pour a glass of water down the commode to rinse down the waste, because the toilet won’t flow properly; we tried unsuccessfully three times to fix it and gave up. (Plus, every couple of days, we have to empty the sewage from the trailer’s tank into a larger storage tank and hire someone to pump it out monthly.) To do laundry, we have to go to the town laundromat, where I end up spending two-hour blocks a couple times a week—a chore and location I actually enjoy, feeling now like the laundromat is a second office. To buy affordable groceries (because Telluride’s market is so overpriced and limited), we have to drive nearly 90 minutes to the nearest medium-sized, affordable city, Montrose, where I also spend time visiting my mom, who now lives in assisted living there.

So this is has become my life, my domestic ultra. If someone asks what I do, I probably should embrace the old-fashioned term “homemaker,” because that’s my main purpose now: building and making a home, and in the process, circling back to the summertimes I savored as a kid. I would not trade it, and so far, I have no regrets.

Et cetera

If the long post above didn’t bore you to tears and you wanna read more….

To learn more about the history of this region and my grandfather’s way of life, check out his memoir,One Man’s West.

Also, I blogged about Telluride and our family escapades in these two earlier posts:

Mining Family Stories for Inspiration and Summiting a 14’er to Reach Into the Past

An Ode to Telluride, Family Ghosts and the Hardrock Spirit

If you’d like to explore some of these mountain trails on foot with me, check out the San Juan Mountain Running Camp we’re launching July 11 – 14 and Sept. 23 – 26—spots still available for both July and September.

Wow! What an absolutely breath-takingly gorgeous place to build a home.

Loved reading this! Your life is my dream that will never happen. I fell in love with the San Juan after 11 Summers living Hard rock as my cation. Thanks and will have to get the books…

Hi Sarah – Yep dirt is everywhere in the mountains. Also local mountain people are accustomed to dirty hands and feet. In the mountains one looses the passion to keep clean. I love to just occasionally wash things just because there is nothing left to wear or the bed sheets are stiff with dirt.

That leaves more time to smell the flowers and enjoy the beauty of the land and the sky!