Get to the summit. Keep going until sunrise.

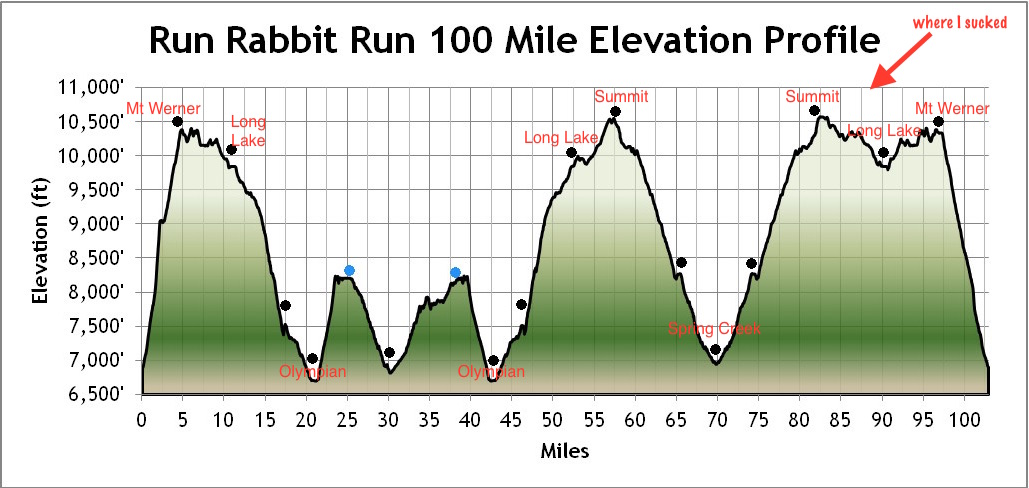

Those phrases repeated in my head while I feebly walked uphill on a dirt road through an aspen forest in the predawn darkness last Saturday morning, around Mile 76 and at 9000 feet of elevation during the Run Rabbit Run 100 in Steamboat Springs. Facing 1500 feet more in climbing over some six miles until the Summit Aid Station, I grasped onto the promise that daybreak would deliver rejuvenation.

That’s the way it normally works in 100s and has worked for me in the past. The sun comes up, enters your pores and works like coffee brewed with half a hit of Ecstasy. You feel energetic, emotional and uninhibited (and consequently, you reveal personal details to your pacer that you’ll later regret and take a poop trailside without really bothering to hide from view). Your stiff hiking gait transitions to a smoother run, and you hallucinate the head of a horned, helmeted Viking warrior in a tree branch, or the backside of a buffalo in a stump. Sunrise is the best part of a 100-mile ultra, allegedly.

So I kept putting one foot in front of the other. Running was not an option due to the combined handicaps of a steep slope, rapid breathing, and anterior shin pain that internally pierced the fronts of my lower legs any time I accelerated.

The route’s elevation profile, annotated to show the aid stations mentioned in this post.

The deterioration of every fiber of my being began after Mile 52, just past the Long Lake Aid Station, sometime in the darkness before midnight when I was with my first pacer, Jacob. The sequence of events went like this:

Miles 0 – 22: I started at 8 a.m. in the less-competitive “Tortoise” division with an earlier start than the Hares who start at noon and compete for the sport’s largest prize purse. My pace was strong but conservative, and I felt better than OK on the first 4000-foot climb up a ski run to the top of Mount Werner, because throughout summer I had hiked a lot of ski slopes in Telluride. Eight or so miles of steady, smooth running after that passed by in a blur. “Find your easy” became a mantra; I found and maintained an easy running pace, and downshifted to hiking whenever running felt hard.

At around Mile 4 after that monster first climb, I said out loud, “Yay, only 99 to go!” because the course supposedly measures around 103 miles. Another runner nearby, who’s a Steamboat Springs local and has done this event several times in the past, told me that no, the course actually is around 109, according to most Garmin measurements from years past. The true distance is a mystery and matter of debate. In any case, I got the first hint that each segment of the route would feel and actually be a little longer than advertised.

Lots and lots of people passed me on the most technical downhill section—a jagged-rock stretch of some three miles approaching Fish Creek trailhead—but I truly felt fine with that and stepped aside to let them pass. A bad fall three weeks earlier still spooked me on the gnarly downhills. “Better safe than sorry” became this section’s mantra. I stayed relaxed and congratulated myself on not tripping. When I hit the paved four-mile downhill stretch to the next major aid station, Olympian Hall at Mile 22, I felt smooth and flowing. So far, so good.

First-place female Courtney Dauwalter excelling on the technical downhill stretch into Fish Creek Falls, where I slowed a lot and let others pass. Photo by Paul Nelson

I took good care of myself at Mile 22, eating and drinking the equivalent of lunch, applying sunscreen before heading out into the blazing midday heat, and strapping on my iPod for the 20-mile stretch.

Miles 22 – 42: Runners wilted on this hot, hilly, not-particularly-scenic section. The struggle was real. But I did relatively well here, helped by the music in my ears (favorite tune on the playlist: 1978’s “Every 1’s a Winner” by Hot Chocolate, a song my son Kyle discovered through a skateboarding video, and he’d play it whenever he got behind the wheel to drive to his first real job this past summer—me riding shotgun, since he only has a learner’s permit and can’t drive alone—and it became a summertime anthem that we’d sing together). We had to go up and down a dirt track with about a 20 percent slope, aptly named “Lane of Pain,” and every time I saw the “Lane of Pain” sign, I said out loud in a voice imitating a monster truck show announcer, “It’s the LANE of PAIN!” I passed lots and lots of runners who had passed me 20 miles earlier on that technical downhill section.

I ran into the Olympian Aid Station at Mile 42 and felt delighted to see both my pacers—Jacob and Terry—waiting for me. I changed my clothes (a brief downpour a couple of miles earlier left me soaked, and I wanted dry, fresh clothes for nighttime). At that point, I had nothing to complain about—no stomach or foot problems, no significant issues. A little crampy in the calves and tired, but eager to pick up my pacer Jacob and start the nighttime stretch. We left the aid station shortly after 6:15 p.m.

Me with Jacob at Mile 42 in the early evening.

Miles 42 – 70: Jacob Kaplan-Moss is one of my clients, and I’ve been training him since new year’s in prep for the Grand to Grand Ultra stage race. But we didn’t know each other very well before that night. Turns out he’s into horses and also went to UC Santa Cruz, so we had a lot to talk about, and we chatted amicably on the uphill back toward Fish Creek Falls.

The route took us back up toward the summit, some 4000 feet of gain over 10 miles, so I wasn’t planning to run that section, save for some short shuffling intervals on flatter parts. I told him I’d run once I got to Long Lake and we hit rolling single track.

At Mile 52ish, around the second pass by Long Lake, I had my first feelings of “uh-oh” and premonition that, like Wasatch 100 two years ago, I would face the consequences of being well-trained for a 50-miler but not for a mountainous 100. It would be a long night.

I started telling Jacob, “Sorry, I can’t go faster … sorry, I need a break…” I tried to focus on all that was going right: hydration and eating felt fine; body temperature felt good (I avoided getting chilled in the high-altitude nighttime air). An almost full moon rose in the sky and made clouds glow with a silvery outline. We were lucky—the winds had shifted, blowing smoke from nearby forest fires away so that the sky was clear enough that a few stars could shine through. But my quads, knees, shins and feet all started to ache mightily.

I had to take breaks from running the long downhill down to the Mile 70 Spring Creek Ponds Aid Station, where we’d meet Pacer #2, Terry Miller, a nice guy and experienced ultrarunner whom I’d met at Hardrock. I felt progressively achy and icky on the descent. “Tell Terry he doesn’t have to worry about me dropping him,” I told Jacob as we entered the aid station.

Mile 70 to the End: So at around 3:45 a.m., Terry and I headed back up the road that I had just run down with Jacob. (Crazy, huh? Why do we do this?)

I told Terry to keep track of our mileage, since my GPS ran out of battery earlier and I had only a simple watch to tell the time of day. I resisted the urge to ask him how far we had gone until I felt sure it was about 4, and when he said, “About two a half,” I wailed, “Is that all?”

Fussing with clothing and poles provided distraction from obsessing about how far to the summit and how long until sunrise. A pocket of frigid air would make me grateful for my jacket, long-sleeve wool top, gloves and leggings. A quarter-mile later, I’d feel hot and bothered and strip the layers off. I couldn’t make up my mind about trekking poles, either. Fold them up, put them away, curse yourself for bothering to carry poles on such a smooth stretch of dirt road. Then stumble and trip, take them out again, try without success to generate momentum by swinging arms and planting those clickity-clack poles.

Terry gamely tried to engage me in conversation and kept reassuring me that I was doing fine time-wise. I brooded and remained silently judgmental until blurting out an order or a random thought, channeling the person I was three decades ago when I identified with Ally Sheedy instead of Molly Ringwald.

“I’m taking a nap at the aid station,” I told Terry in a tone that dared him to argue with me. He wisely tried to change the subject.

Feeling decrepit physically is part of the process in a 100-mile ultra. I get that. It’s supposed to be hard and hurt, as I tell my clients. I could have handled that alone. Feeling down in the dumps mentally, however, threatened to do me in. All my coaching about the power of positive thinking, about faking optimism to make it real, about using mindfulness and acceptance to acknowledge and move through negative thoughts—none of that was working.

It wasn’t working because I didn’t care enough. I didn’t genuinely care about this race; I entered it to earn qualification for the Hardrock lottery, not because I felt excited about this event. I didn’t train enough. I felt worn out from traveling back East and moving my daughter into college three days prior. I had an excuse for every mile. “Just finish” became a recipe for ambivalence, and ambivalence became a deep desire to be done and over with it. I wanted to be a fast runner, not a slow slogger. I wanted to feel the thrill, not the drudgery. Feeling so miserable and not into it made me second guess the main goal of doing Hardrock someday. If I can barely make it through one night at this mountain ultra, how would I handle going into a second night at Hardrock (which probably would take me 40 some hours)? My thinking went: I don’t deserve to attempt Hardrock because I can’t execute this qualifier with dignity or determination. Doing 100s doesn’t have to be my thing anymore. I should drop at Summit so I don’t get the qualifier and don’t have to belabor the Hardrock process. Take a nap first, then decide.

The sun came up. Terry took out his phone to capture me at sunrise. “I’d rather you not,” I said and refused to look at him.

Terry’s photo of me at sunrise, heading up to the Summit Aid Station.

Sunrise revealed a few trucks and campers parked here and there. Eyelids heavy, I engaged in extended internal debates about which vehicle seemed like it would belong to an owner that I would feel comfortable enough asking if I could lie down in the back seat for a while. I visualized getting into these trucks in such detail that my thoughts crossed over to dreaming, and I realized I had slipped into a wobbly sleep-hiking.

The higher the sun rose, the brighter it got, the more I wanted to close my eyes. God damn it, the sunrise isn’t working its magic.

Another pocket of cold air hovered around the summit, so I hoped they’d have blankets on the medical cots. I made it to the aid station tent and saw a heater and some chairs, but no cots. So I took a chair, pulled it as close as possible to the heater and tried to power nap. Terry got me a bowl of scrambled eggs and bacon, which tasted surprisingly good, so I woke up enough to eat. Then, just as I was drifting off, a woman I met the day prior came in with bouncy energy. It was Wendy Wheeler-Jacobs, slightly older than I at 50, a notable runner and race director from the Pacific Northwest. She took a seat next to me and asked how I was doing.

“Not good, not my day,” I mumbled.

“Well, let’s go then!” she told me.

I should have hitched my wagon to Wendy’s momentum and followed her right then and there. I so very much admired and envied her energy. That should have been me—a closer. I’ve had a strong final 20 miles in past 100s. I’ve perked up with the sunrise. But I let her go. Not my day.

I spent an unknown number of minutes eyeing a van parked nearby and imagining a scenario in which I stretched out on the back seat and had a long, involved conversation with the aid station captain during which we clarified that the van was close enough to the aid station that my entering it would not constitute a DNF. This scene took place with vivid reality but, in fact, I was sitting in a stupor spooning eggs into my mouth and losing the feeling in my cold, stiff legs.

I woke up enough to realize I needed to warm up my legs, so I stood and bent over the chair, leaning on the armrests for support. I backed my butt up as close to the heater as possible so hot air would blow up my backside and hopefully dry the damp crotch lining that was chaffing my inner thigh crease.

Flopped over that chair, my butt pleasantly roasting in the heater, my head hanging down and my jaw open to drool, I drifted toward unconsciousness in a bent-over rag-doll position. Ahh….this feels more like it.

A question came out of nowhere, like an alarm that shatters silence and rips through slumber. A man’s voice from the corner of the tent, loud enough for everyone who was milling around the aid station to hear.

“Are you Sarah Lavender Smith?”

Huh? I opened my squinty eyes just enough to make out someone I didn’t recognize. He was sitting and looking at me expectantly.

“I got your book,” he said. “I work in leadership and use it.”

Was this really happening? I wanted to laugh and ask, Are you kidding me? Wanna take a picture of me like this? Did he mean he used my book for leadership training, or for his running, or for both, or—whatever, I was totally confused and caught off guard, the ultrarunning version of a minor celebrity who looks fat and scowling in a tabloid photo.

“Ah, yes. That’s really nice. Really appreciate that. What’s your name?” I don’t remember what he said. I felt as if I were waking up from an exposure dream, still half naked.

The question echoed internally, “Are you Sarah Lavender Smith?” Are you the person who will walk the walk, not just talk the talk? I had a bookload full of advice I expected others to follow. Don’t ask of others what you’re not willing to do yourself, to paraphrase Eleanor. I had to get the fuck out of that aid station and back on trail. I left while Terry was grazing at the buffet table, and he had to scramble to catch up.

We had 13 or 15 or so miles to go. Who knew what the exact mileage would be, it would be long.

Summit Aid Station back down to Long Lake should have been runnable. Lovely, smooth singletrack on the Wyoming Trail through aspens and alpine meadows. It’s like the Cal Street stretch of Western States—it’s a crime to bonk and not run there! So I would take a few steps to try running, but then I would walk again. “Can’t do it,” I told Terry. The foot ache, the spiked heart rate, the shins, the knees—every body part protested what I was doing to it.

Runners kept passing us, each taking a piece of my pride with them. Terry momentarily cheered me up by sparking a conversation about favorite movies, but my inability to remember titles or actors’ names made me momentarily dwell on my mother’s memory loss and feel paranoid that I was already showing signs of losing my mind. Speaking of which, I started seeing dog faces, Viking heads and buffalo bodies in the woods, but no moose, and I really wanted to see a real moose.

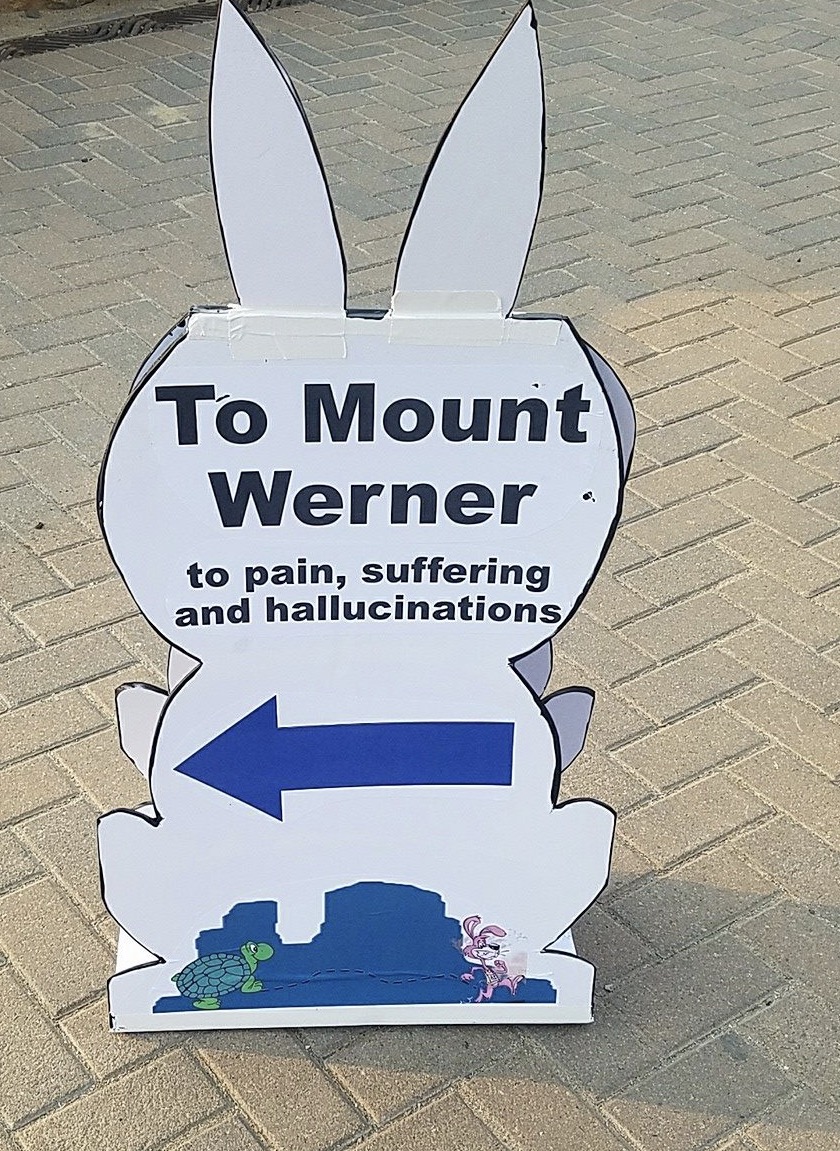

An accurate sign.

This section—from Summit back to Mount Werner—seemed to go on forever. Trite but true. I hated being so slow and feeling so infirm. I hated the logic that I wanted to cover 100 miles so I could be done with 100 miles because I didn’t actually want to do the full 100 miles. Ugh, none of it made any sense.

I took extra time to eat and put on sunscreen at the final aid station atop Mount Werner. I could have and should have finished this course in 30 hours or less. But I could do the math with my pace and the distance, so I knew it’d be 31 and change. Why worry, why hurry? Just get to the finish.

All summer, I finished runs on long, steep downhills. I actually felt prepared for the final segment of this course. But I couldn’t muster extended running on that steep downhill back to town. Running intervals of a few minutes at a time, then taking a walking break, was all I wanted to do, all I cared to do.

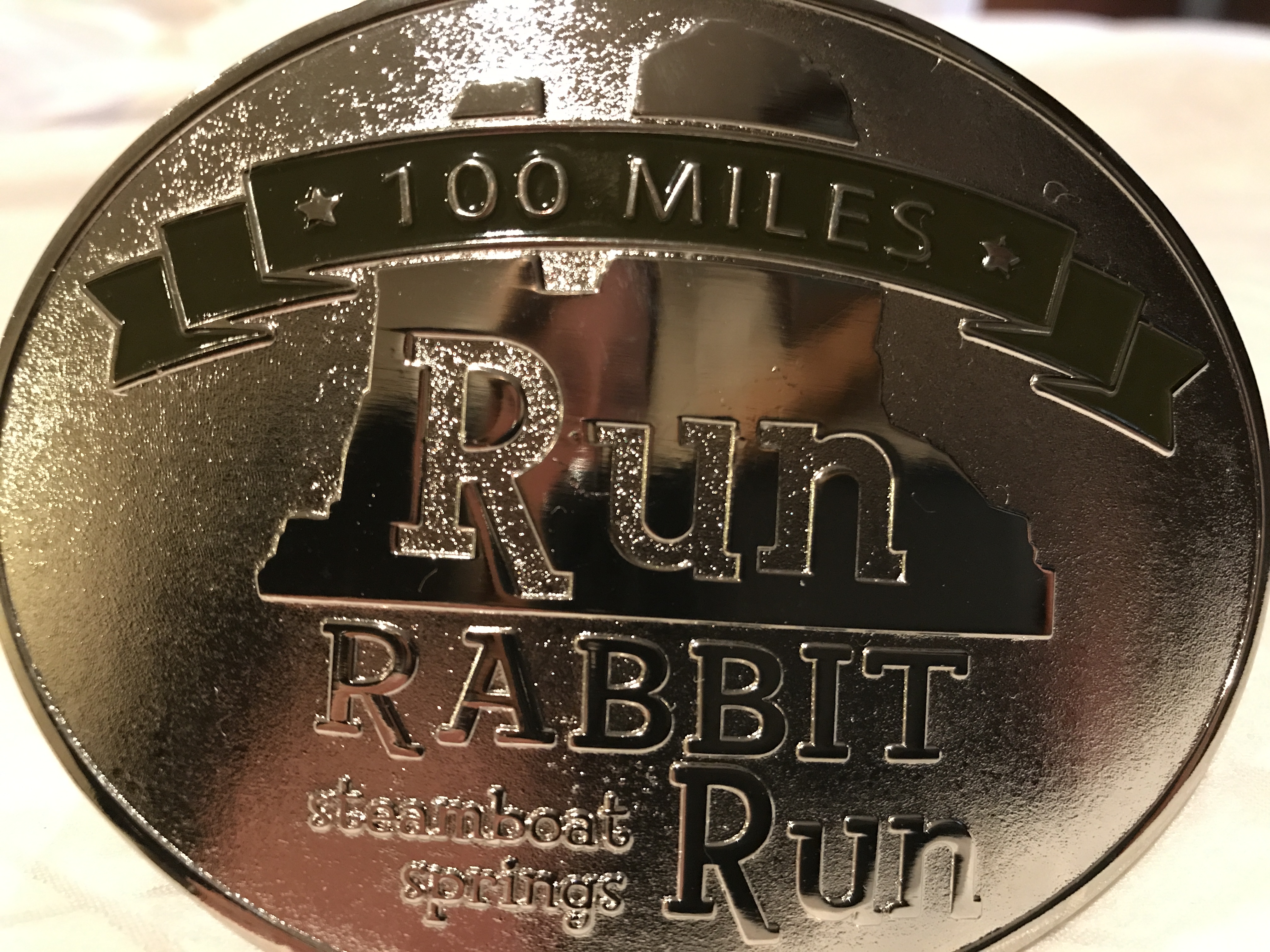

Yeah, we made it back. Of course we did, I believed I would. But crossing the line in 31 hours, 7 minutes felt so anticlimactic, so unemotional, almost businesslike, like meeting a deadline at work on a Friday and then heading to happy hour to start the weekend. Got it done.

At the finish with my pacer Terry Miller and relieved to be done.

I need a break, I know I do. Finishing a 100-miler should feel a lot more celebratory and special than that.

I sat in a stupor on the porch of the Sheraton’s restaurant overlooking the ski resort, the start/finish line in view, listening to other runners celebrate or commiserate about their day. Their chatter and camaraderie brought me back to life. I heard one woman, who looked showered and fresh because she finished hours ahead of me, say to someone, “Yeah, I had a really great day out there.”

That’ll be me again, someday. I’m feeling more positive about the experience and proud of my tenacity with a few days’ perspective. It was worth the effort. I’ve got the Hardrock fever again, glad to have completed a qualifying race to enter the snowball’s-chance-in-hell shot at getting a spot. (Crazy, huh? Why do we do this?)

I’m coming away from this event full of gratitude for my pacers, Jacob and Terry; for several Steamboat Springs runners who welcomed me and came to my book-signing event a couple of nights before the race; and for the Run Rabbit Run 100 RDs and volunteers. During a week of natural disasters, when smoke created a haze around northwestern Colorado and ash rained down on Steamboat Springs, we were so fortunate that nearby fires didn’t shut down the event; in fact, the sky cleared remarkably on race day.

A pretty shot of the course and blue sky. Photo by Paul Nelson

Here’s how I looked before the race (with bunny ears that all participants were asked to wear for photos). I’m looking and feeling smiley again. But I also can see in my face and eyes below that I went into this race tired. Now, time for sleep and rest!

Gotta show the buckle.

End note: Thanks so very much to everyone who has purchased a copy of my book, The Trail Runner’s Companion: A Step-by-Step Guide to Trail Running and Racing, from 5Ks to Ultras. Please consider ordering a copy, or leaving a customer review, at this link. You can check out reviews and excerpts of it here.

And yet you got it done!!! Practicing perserverance as if Hardrock is already on your calendar. Nice job!

Always so much fun reading your stuff SLS! Look at the bright side – when a race goes really well there’s not much to write about. As the Rocket always says, “It’s not whether you win or lose, what’s important is that you have a good story to tell.”

You do, and you told it well! Hooray.

TJ thank you so much! Means a lot to me.

Cocoa Butter, You leave me speechless with your reporting and as everyone knows leaving me without lots to say is an almost impossible task. Great job of persevering and accomplishing the goal. I can only hope to do half as well when my time arrives. Proud of ya honey, you’re the real deal. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it. Fondly, E. “Rocket”

Way to get up out of that warm chair and finish what you started! See you in Silverton 🙂

Amazing feat, Sarah! You should really be proud of yourself. I totally enjoy reading your blogs.

Great race report SLS and good on you for getting it done when you were having a less-than-stellar trip through the mountains. The hard races are always much more interesting to read about than the great ones and toughing it out when you are having an awful time is much more impressive than a fast time on a good day. Way to go!