I have been waiting a long time for a book like Jason Koop’s excellent new release, Training Essentials for Ultrarunning: How to Train Smarter, Race Faster, and Maximize Your Ultramarathon Performance (Velo Press).

I’ve read several books about ultrarunning—those based on memoir (e.g. by Dean Karnazes and Scott Jurek), and those aimed primarily at getting rookies to reach an ultra finish line (e.g. by Bryon Powell, Hal Koerner and Krissy Moehl)—but for more precise knowledge about training for long-distance running, and the physiology behind it, I relied heavily on Jack Daniels’ Daniels’ Running Formula, 3rd Edition. Daniels is a legend who coached Magdalena Boulet to become an Olympic marathoner before she transitioned to championship ultrarunning (see earlier post for why I admire him). The problem is, Daniels has very little experience coaching for distances past 26.2 miles.

Koop fills a gap in the literature with this comprehensive resource for high-performance ultrarunning, written for serious ultrarunners and coaches. Director of Coaching for Carmichael Training Systems (CTS), Koop is an accomplished ultrarunner himself, and he coaches elite athletes including Dylan Bowman, Kaci Lickteig, Dakota Jones, Alex Varner, Jen Benna and Missy Gosney, several of whom make contributions to the book. The book is co-authored by Jim Rutberg, another CTS coach.

But don’t let this post be a substitute for actually reading the book. There are many valuable sections I’m not going to touch on (e.g. the in-depth examination of blister prevention and treatment; the chapter on “The Physiology of Building a Better Engine,” which provides a plain-English primer on the science of how our bodies take in, convert and store energy; or the final chapter’s “Coaching Guide to North American Ultras” with pro tips on ten iconic ultras).

Here are some of Koop’s big ideas to guide your training:

Cardio fitness rules, and speedwork belongs in base-building.

Cardiovascular fitness is a central focus of Koop’s book, and he warns against shortchanging performance by over-emphasizing volume (cumulative mileage and time on feet) and under-emphasizing intensity. Moreover, he details how cardio fitness improves every aspect of your ultra performance and helps prevent run-stopping problems. For example, got GI distress in the middle of a race? Well, it’s not just a problem related to what you ate or when you ate it. It’s also partly due to (lack of) cardio fitness. Your body is working hard to deliver oxygen to your muscles and to your skin to dissipate heat, and thus is diverting blood from your digestive tract, slowing your gut’s ability to process food. If you improve your body’s ability to transport and process oxygen, you’ll improve every system’s ability to function, including digestion.

Moreover, trail/ultra runners make a mistake if they do only conversational-pace, low-intensity running early in the season and progress to speedwork later—or worse, skip high-intensity running altogether. Yet it’s common for ultrarunners, if they do speedwork at all, to incorporate medium-intensity tempo-pace runs first into their training (long intervals at or near lactate threshold), and then perhaps graduate to short, fast intervals. Or they skip the short, fast stuff altogether, thinking that kind of training belongs within the purview of 5K-to-marathon road racing.

Koop views this as backwards. He argues it’s better to do VO2 max work—that is, short intervals, lasting 1 to 3 minutes at a perceived exertion level that reaches 10, with time at high intensity totaling 12 to 24 minutes for a single workout—a couple of times a week, ideally on an uphill incline, early in the training cycle. That way, you build your cardio engine and raise the ceiling on your maximum aerobic capacity. Boost VO2 max first, then work on lactate threshold.

You may worry that this level of speedwork could trigger injury. The key is adequate recovery: recover an equal amount after each interval (e.g. 2 minute recovery after 2 minutes at VO2 max), and run easy or rest on days between the high-intensity workouts.

The closer you get to an event, the more specific your training should be.

Most of us know that “specificity of training” is a bedrock principle. It means you should train for the conditions specific to an event; so training for, say, a 24-hour timed event on a flat, one-mile loop should be quite different from training for a high-altitude point-to-point 100-miler.

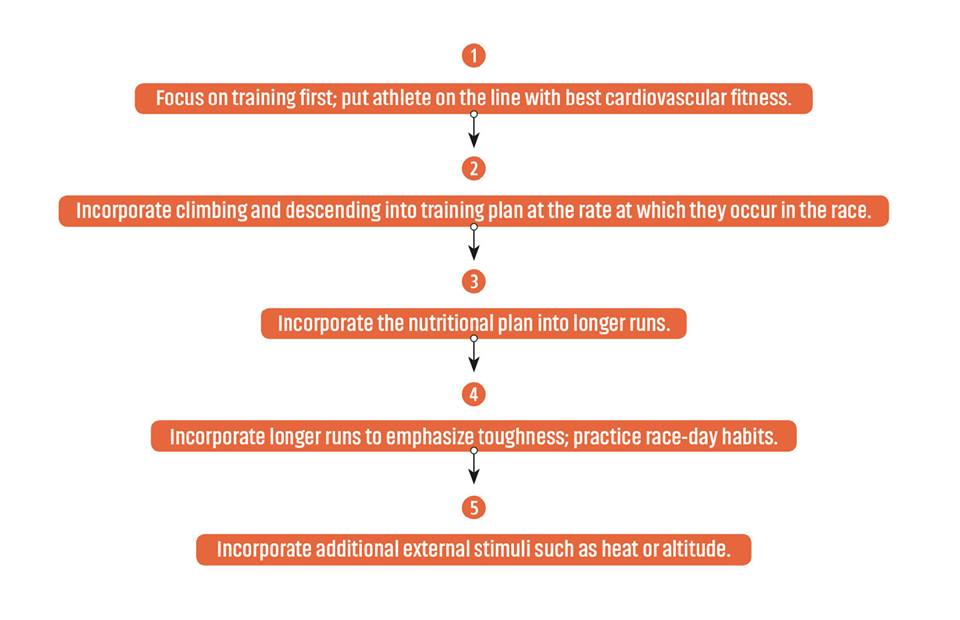

But Koop says this specificity—practicing course-specific challenges—should come after you’ve done the essential work of developing the following: your cardio engine, your ability to handle climbs and descents, and your nutritional plan (i.e. your gut’s ability to adequately refuel and rehydrate without rebelling on long runs). Get those fundamentals in place before you concentrate on the nitty-gritty of elevation profiles, environmental adaptations (like heat or altitude), or terrain challenges (like sand or rocks).

Heart-rate monitoring is flawed. Gauging the rate of perceived exertion works better.

I can’t tell you how happy it made me to read the section on “Measuring and Personalizing Training Intensity” in Chapter 7. After hearing so many others evangelize heart-rate training, I tried over the years to use a heart-rate monitor (HRM)—both chest strap and wrist based—to improve fitness and get the most out of workouts. I monkeyed around with various formulas and methods to calculate my maximum heart rate and training zones. But I often felt frustrated, because targeting a specific HRM number did not seem as accurate as what I felt to be right when aiming to reach a level of intensity, say 90% max heart rate.

“Many factors affect an athlete’s heart rate, and those factors reveal that heart rate response is not reliable and predictable enough to be an effective training tool,” Koop writes, and proceeds to list and explain the myriad factors that screw with a HRM reading: core temperature, caffeine and other stimulants, excitation/nervousness, hydration status, elevation, fatigue and “cardiac drift”—a term to explain what happens when you exercise, especially at higher intensities, and your heart works to deliver blood to the skin to cool off through perspiration. As your body transfers fluid from your blood stream to produce sweat, your heart has to pump even harder to deliver the same amount of oxygen to your muscles; “as a result, your heart rate will increase slightly as exercise duration increases, even if you maintain the same level of effort.” If a runner is fixated on maintaining heart rate at a specific number on the HRM throughout a workout, rather than allowing it to increase slightly to account for cardiac drift, then the workload actually falls slightly, and the workout can lose some of its effectiveness.

A better gauge of workout intensity is the good ol’ scale of 1 – 10 for perceived exertion, combined with the “talk test.”

Using this scale, “an endurance of ‘forever’ pace would be a 5 or 6, a challenging aerobic pace would be a 7, lactate threshold work occurs at about 8 or 9 … and VO2 intervals are the only efforts that reach 10.” You can further gauge exertion by monitoring your breathing and ability to talk: a 5 or 6 allows for rhythmic, moderate-depth breathing and comfortable conversation, whereas short intervals for VO2 max create short and rapid breathing and allow for only single words to be uttered between breaths.

I find it funny but great that a precision-oriented, empirically grounded coach like Koop prefers rating of perceived exertion for monitoring different workout intensities. It’s grounded in common sense and intuition; it’s simple, it’s natural and it works. I highly recommend the whole chapter devoted to running intensities and key running workouts.

On a side note, I bet you that when Jason Koop reads this, he will roll his eyes anytime I make a self-reference, as with the previous anecdote. You will not find personal stories about Koop in this book (save for one small one, about the time he ran with an engagement ring on his first 100-miler, the Leadville 100, to propose to his wife at the finish line). Koop abhors inserting one’s personal bias into coaching advice; he calls it “the N of 1 mistake”: “If I ever use an ‘I’ statement in my coaching, I consider it a flaw. A coach should certainly take his or her own experience into account. However, relying on that experience, the N of 1, is the ultimate coaching flaw. … Ultrarunning coaches routinely regurgitate their personal training for their athletes. And runners who coach themselves tend to insert too much of their own bias into the process.”

I agree—to a point. But I like to share personal experiences because I appreciate gleaning information from others’ experiences. I think it’s fine—and often, helpful—to tell anecdotes as long as there’s an understanding, “This worked (or didn’t work) for me, and it may or may not work for you…” We can all learn something from reading race reports or listening to runners talk about their highs and lows in forums like UltraRunnerPodcast. Bottom line, I wish Koop had shared more of his stories in this book—and he has good ones to tell! (Listen to our 2014 UPR interview with him to hear a great one.)

Balancing hydration and electrolyte levels is a delicate, dangerous dance, and you need to know the steps to prevent failure during ultras.

Koop’s chapter on “Fueling and Hydrating for the Long Haul” should be required reading for any ultrarunner. Rather than try to recap the good advice here, I’ll mention one section worth bookmarking: a list of symptoms and interventions for various states of hydration and sodium levels. Using a grid, he charts the different combinations that can occur, from too much fluid and too much salt (overhydrated and hypernatremic), to too little of both (dehydrated and hyponatremic). You’ll understand how you got there, what the symptoms are (e.g. puffy hands, nausea, dry mouth, dark pee, no pee … the list goes on), and how to get back to a more normal level.

Why does this matter? “Fueling errors are easy to fix. … Even if you eat the ‘wrong’ thing, you will still, eventually, get sugar into your body relatively quickly. If you screw up your hydration status, the fix is not so simple. Compared with fixing a bonk, the remedy involves far more complex mechanisms of hormonal regulation and electro-chemical gradients. In addition to sounding more complicated than ‘eat sugar and let it digest,’ these mechanisms of regulating blood volume are indeed slower. They take hours to rectify if disturbed, and the series of steps an athlete may need to take is often complicated. … If you screw up your hydration enough, you could end up in the hospital or even die. The magnitude of the ‘penalty for failure’ in this respect is precisely why hydration, sodium and thermoregulation are the most important nutritional aspects to understand while preparing for an ultra.”

Forget fat adaptation.

Many ultrarunners tout the benefits of high-fat/low-carb diets combined with lower-intensity training to achieve “fat adaptation” or “metabolic efficiency.” I’ve been skeptical of the ability to maintain an extremely-low-carb diet, and of the wisdom of exclusively running at low intensities to promote fat burning. My hunch has been that if these runners do well at a race, it’s not necessarily fat adaptation that deserves most of the credit but, rather, they’re experiencing the benefit of significant weight loss from an overly restrictive diet, and the weight loss helps them run faster and more efficiently. (And that’s risky because significant weight loss from a restrictive diet is difficult to maintain and can trigger disordered eating and other problems.)

Koop explains that fat adaptation involves sacrificing higher-intensity training, and in his view (and mine) the tradeoff isn’t worth it. “You can become more fat-adapted and burn more fat, but you will arrive at the race with less fitness due to reduced training workload. Or you can eat a high-carbohydrate diet, burn less fat, complete higher workloads in training, and arrive at the race with greater fitness. For me the choice is easy,” he writes. “Fat adaptation may cause a shift in how you produce energy, but it doesn’t help you deliver energy more quickly to working muscles. … Mile for mile and effort for effort, ultrarunners stand to gain more from improving their cardiovascular engine than from anything else.”

Weekly training plans from books or the Internet are limited in their usefulness and could do more harm than good.

As a coach myself who develops individualized weekly training plans, which I constantly fine-tune in response to the client’s feedback, I sometimes warn runners about the downsides of cookie-cutter training plans available online. Therefore I’m grateful that Koop emphasizes the principle of individuality—that training should be based on an individual’s own physiological and personal needs—and he doesn’t include one-size-fits-none training plans in his book.

“A pre-written training plan is bound to under- or overestimate an individual runner’s response to training and his or her ability to stick to the schedule. It will end up being way too hard and will run you into the ground, or way too easy and will not adequately prepare you for the demands of the event,” he writes. If you self-train, it’s better to design your own plan based on sound training principles, and be ready and willing to regularly adjust the workload (e.g. the duration and intensity) of your training as you adapt and make progress (or, as you suffer setbacks or life stressors and need to scale back accordingly).

Care to crosstrain? Consider the tradeoffs.

I don’t completely agree with Koop on everything; for example, I think he kind of throws the baby out with the bathwater in his criticism of crosstraining. For improved ultrarunning performance, he says it’s better to use your extra energy or time in the day for run-specific training, or simply to rest. It’s fine if you want to do yoga, CrossFit or some other activity for general fitness and enjoyment, but he says it won’t really make you a better ultrarunner.

I, however, believe that a moderate amount of dynamic stretching, strength conditioning, plyometrics and balance work is worth it. The right combination of these activities can help improve biomechanics and prevent injury, along with promoting strength and flexibility.

In an email to me, Koop countered, “Strength and crosstraining and plyos blah blah …. I always look at this through the lens of what the tradeoff is. So, if you are talking dynamic stretching or maybe the core stuff, it’s just the time. When you are talking plyos or strength, you are substituting workload for something that is less specific. So, I will always take the stance that a higher workload that is specific to the competition modality (running in this case) will always win. … Now, crosstraining does have its place if you want to be more well rounded, pick your kid up over your shoulder, or just not be a one-dimensional endurance athlete. But, make no mistake that is does so with a compromise of making a better runner. Sometimes that compromise is big, sometimes small, so it’s all about your goals. Any of the studies that have been done that add strength (and usually plyo specifically) to a running program and see results are flawed because the workloads are not equal. The control group keeps their same run program, and the experiment group does the run program plus strength training, therefore the workload is higher and they should see bigger adaptations.”

So there you have it—you be the judge. I’ll keep carving out time to hit the floor for core work, burpees, balancing on a Bosu ball, and other movements that Koop might shrug off.

But to fine-tune my peak training for Western States 100 and to develop a race-day plan, I’ll keep Koop’s book nearby for reference, and I recommend that other ultrarunners do, too.

[UPDATE: Check out the comment thread below; Koop makes some points for clarification in response to readers’ questions.]

Thanks for the review Sarah!

This is a great review. I read his book too and I loved it. I completely agreed with your statement on HR training. It is preached. I have never been a fan. I also agree with you on the “fat for fuel” argument too.

I just finished this book and also highly rate it. I’m not going to argue with a sports scientist such as Jason Koop but I still do not quite understand the argument against heart rate training. Surely whatever variable (heat, lack of sleep, time on feet) that might cause your heart rate for a given pace to change would also affect your pace at a given RPE? Also surprised at the dismissal of cross training and not a single mention of injuries and injury prevention which surely screws up more training plans than anything?

Lastly, how does Dean Karnazes get to write a foreword for this book after having written one for Unbreakable Runner (which I am now ashamed to having purchased before finding Koop’s book).

Thanks for reading and commenting! I’ll let Koop decide whether to respond; I don’t want to misstate his view. But as for Dean K., he writes forewords and endorsements for several books. He and Koop worked closely together a decade ago when DK did his run across the U.S.

Des,

Some great thought here!

1) you are right that RPE does shift around when fatigued/fresh. But it does so in the direction of fatigue/freshness (lower RPE when fresh, higher when fatigued). so, you will typically be in the right intensity for your state of fatigue. HR does the OPPOSITE (for most cases). It’s depressed when fatigued, and elevated when fresh.

2)RE cross training- I’ll always take more specific work vs less. This will be debated forever and forever in endurance sports

3) I do give a little mention to injuries in the book. Mainly in the fact that uphill interval work is a hedge as it reduces GRFs and that the risk:reward for downhill work is too high IMO. However, the main injury prevention things a runner can do is simply control their workload, specifically their ATL:CTL ratio. I felt that was too advanced topic and simply left it on the cutting room floor (2nd edition, perhaps???). The other thing that might be worth mentioning is proprioceptive work, which has proven efficacy and does not interfere with the run workload (like strength training). Once again, the book was long enough….

RE: Dean’s into. Funny you mention that. First off, I was honored to have him write the intro. I have known Dean for a long time and he didn’t blink when I asked him to write it. Brian MacKenzie, and Matt Fitzgerald (author of How Bad do you Want It? among others) and I were on one of Dean’s Badwater crews several years ago. It was a hoot. Although Brian and I are on very opposite sides of the spectrum, we have much respect for each other as professionals as we’re all trying to further aspects of the sport.

koop

Wow, great review, and while I am sort of done with ultras (unfortunately), worth the read and recommendation. Seems I would agree with a lot of things here.

This was a great review! My instinct is to agree with a lot of what Jason appears to be saying (the heart rate thing, the fat burning thing), which makes me feel like I could really get something from the book. I will likely never be a “serious” ultra runner, but I suspect lots of this would apply to my four hour trail Half Marathons and such.

Great review with lots of things to think about!

Great review, thanks! As a fellow coach who prescribes intensity, I loved it too, and agree about training plans and fat burning, among other things. I disagree with throwing heart rate out, however. His and your reasons forI why HR is unreliable are precisely the reasons I like to see where my clients’ heart rate is: if someone is sick, training at altitude or in the heat, didn’t sleep well, etc, then the corresponding higher heart rate is telling me the stress on the body. I think RPE can can lull people into training too hard, resulting in injury, if used exclusively. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Alison,

I might use HR after the fact as one measure of fatigue/freshness (key word might, you have to have consistency and use it alongside subjective feedback). The fact of the matter is that when you use subjective measures to get a fix on the same things (sickness, lack of sleep) that always beats any objective measure you use (HR, HRV, etc). There have been many, many studies on this, subjective measures generally do a better job on this consistently (see- Saw, Main and Gastin 2016 and others).

But I would never use it as an intensity gauge for precisely the reasons you mention. On the RPE side, it is actually a hedge AGAINST training too hard as RPE is elevated when you are fatigued resulting in running slower/easier when you need to.

koop

Like Allison, I disagree on discrediting heart rate monitors. First of all, though it is not perfect, no device or measurements isn’t flawed. Even RPE is flawed! It could be changes by your mood or othee factors. Second, using max hr is NOT accurate. I recommend to read “total heart rate training” for more explanation.

I’ve been using hr since day 1 and im able to modelize my training load, see my fitness, avoid overtraining with HRV, compare workouts, pace myself at an ultra. Sure, its not 100% accurate and that’s why I also use pace when possible as well as my own awareness and experience.

Its all a matter of taste and colors

Jason, I would have loved reading about the CTL ATL ration but even the TSB for race performance. So far I’ve been following Joe Friels advice on a CTL betwen +5 and +10 max and it seens that it avoids running me into the ground. By the way, those CTL values are generated from my heart rate data, just sayin’

I’ve also been waiting a long time for a book aimed at the serious ultrarunner. But I am perplexed here by the absolute dismissal of LCHF as a viable training strategy. I think maybe Koop misses the purpose of LCHF for many of us. What it gets me is taking nutrition off the table in races, and more blood flow to working muscles, as less is required for digestion. I easily get by on 100 cal / hour, for (so far) up to 30 hours; I get this from a little Coke, which is easy to digest. Meanwhile my competitors are trying to choke down 300 cal / hour, and puking. Even when they don’t puke, nutrition is still a serious concern for them that must be managed. Not for me. That’s a huge advantage.

In the year and a half since I’ve gone LCHF, I’ve set two age-group ARs (200K and 24-hour, for over 50) and many PRs (including the CR, by 12 miles, at the event Sarah linked to above, “a 24-hour timed event on a flat, one-mile loop”). In 17 ultras during this period, I’ve never bonked (except at Miwok 2015, where I was experimenting, and went down to 50 cal / hour) or had any GI issues whatsoever.

There are plenty of top ultrarunners who are LCHF. Whether it makes sense depends to some extent on the race goals. Granted you lose speed. In a 24-hour, this doesn’t matter — unless, I guess, you’re going after Kouros’ WR. 9-minute miles all day will get you 160 miles, close to top-10 all-time by an American. You are limited by accumulated muscle damage, not high-end performance.

Even so, Zach Bitter just ran an 11:43 100 miler on LCHF, about a 7:00 pace. So it is possible to retain some speed.

Bob,

You certainly have had a lot of success! Rather than offer up my own opinion, I’ll just bring in some of the non-biased experts in the field, and a little math.

First go here and view the velocity/time curve and the amount of cal/hour you can get maximally from keto-adaptaiton (the far end of the bell curve for LCHF).

https://twitter.com/TStellingwerff/status/602927159045267458

According to the curve the maximum output you can get in this state is about Bitter’s 100M performance (3.1 Hours for a marathon or about 7:00 pace for a 60kg runner).

Then, I woudl just go here and listen to a couple of experts talk about it. In an effort of full disclosure, one of our coaches works with the host of the show. I have no affiliation with Dr. Burke.

http://www.scienceofultra.com/podcasts/19

You have some good points. For a lighter, slower runner running a 24+ hour race, who constantly has GI issues, maybe, just maybe this is a viable stragety. I still don’t think it’s the best strategy, but I’d at least consider it under some very limited circumstances.