With springtime trail ultras on the horizon, I’m ramping up my training by adding speed and volume, reducing alcohol and portion sizes to lose holiday-season weight, and trying my best to sleep at least 8 hours nightly.

In the past, I’ve written that exercise, nutrition and sleep work together like a three-legged stool: They’re each essential for supporting endurance performance and overall wellness.

But wait—I’ve been neglecting something, perhaps the most important pillar of success for ultrarunners and other endurance athletes.

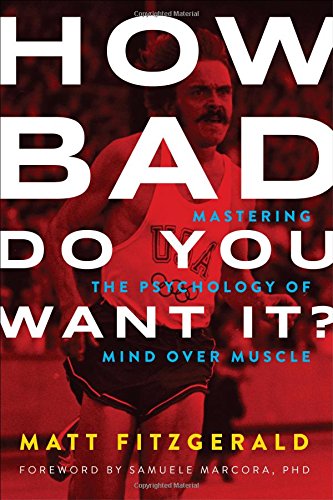

According to Matt Fitzgerald, a well-respected coach, author and sports nutritionist, that thing is mental fitness. Fitzgerald—who writes for Competitor and other magazines, and whose books include Racing Weight and 80/20 Running

—dives into sports psychology in his worthwhile new book, How Bad Do You Want It?: Mastering the Psychology of Mind over Muscle.

“Mental fitness” is Fitzgerald’s term for “a collection of coping skills—behaviors, thoughts and emotions—that help athletes master the discomfort and stress of the athletic experience, mainly by increasing tolerance for perceived effort and by reducing the amount of effort that is perceived at any given intensity of exercise. … It’s mind over muscle.”

“Mental fitness” is Fitzgerald’s term for “a collection of coping skills—behaviors, thoughts and emotions—that help athletes master the discomfort and stress of the athletic experience, mainly by increasing tolerance for perceived effort and by reducing the amount of effort that is perceived at any given intensity of exercise. … It’s mind over muscle.”

If you’ve ever worried about how a race will feel, or about how you should pace it, or about how you’ll perform relative to your competitors (and what serious runner hasn’t experienced these thoughts and feelings?)—or, if you’ve ever cared passionately about a finishing time goal—then you will relate to and likely benefit from the stories and research in this book.

Fitzgerald starts by setting his thesis apart from traditional sports psychology, which he calls “a hodgepodge of techniques that [are] overtly nonphysical, such as visualization and goal setting,” and he endeavors to elucidate the “psychobiological model of endurance performance,” which “views mind and body as interconnected, with the body distinctly subordinate.” The body is subordinate to the mind because what affects our performance is rarely a real physical limit (e.g. dehydration) but rather a feeling or perception (e.g. feeling thirsty).

He points out, “Rarely do champion endurance athletes credit their physical capacity for their success. More often, they insist that their advantage lies not in having more to give but rather in being able to give more of what they have.” They run with “heart” (“heart” being a metaphor for mental fitness) and give it their all. This book is all about understanding what limits your ability to give all that you have or are willing to give to a competitive endurance effort, and how champions have overcome those limits.

He wanted it bad: Zach Bitter setting a new American 100M track record Dec. 20, 2015, in 11:40:55 (photo courtesy Israel Archuletta/Aravaipa Running). Zach wrote on iRunFar.com: “The final 15 miles felt like an eternity, but I was able to keep it together enough to get a 100-mile PR and lower my own track 100-mile American record by six minutes and 26 seconds.”

My favorite aspect of the book is each chapter’s opening story, which illustrates a real-life example of an elite-level athlete’s success or failure. With the talent of a top sportswriter, Fitzgerald re-creates the setting and performance of numerous marathoners, cross-country runners, cyclists and triathletes.

For example, in the “Brace Yourself” chapter, Fitzgerald spotlights Jenny Barringer and the 2009 NCAA Cross Country Championships—a disastrous race for the runner whom everyone assumed would win handily: “The greatest female college runner in history crossed the finish line 163rd in her last collegiate race.”

Fitzgerald analyzes how and why “her implosion seemed to suggest she had been brought down not by anything physical but by a feeling.” Then he artfully peels back the layers of the athlete’s head game as it relates to perceived effort: “The first layer is how the athlete feels; the second layer is now the athlete feels about how she feels.” When you feel worse than expected during a race, you tend to develop a bad attitude about the discomfort and slow down even more.

One takeaway is to brace yourself for the hard effort; that is, instead of suppressing or fearing pain when anticipating a hard effort, a better coping skill is to anticipate and accept it.

“There is temptation to hope—perhaps not quite consciously—that your next race won’t be one of those grinding affairs. This hope is a poor coping skill,” he writes. “Bracing yourself—always expecting your next race to be your hardest yet—is a much more mature and effective way to prepare mentally for competition.”

In the chapter on “The Art of Letting Go,” Fitzgerald profiles Australian triathlete Siri Lindley and her struggle with “choking,” which is “a kind of ironic self-sabotage” because “the desire to maximize performance and achieve a particular outcome creates a feeling of pressure. This feeling of pressure compromises performance and ensures that the wanted outcome is not achieved.”

In his riveting retelling, Siri (with the help of her coach) lets go of this pressure and “goal obsession,” and focuses more on training than on outcome. “A large body of psychological research has demonstrated that the more time people spend fantasizing about desired outcomes—everything from passing school exams to losing weight—the less effort they put into pursuing them and the less likely they are to achieve them. … Set free to focus on racing rather than winning, Siri proved to be faster on tired legs than she had been previously with fresh legs and a self-conscious mindset.”

Another favorite chapter, “The Answer Is Inside You,” studies the 1995 Ironman World Championship in Kona, when seven-time past winner Paula Newby-Fraser collapsed before the finish line, following a season of significantly higher training. Fitzgerald uses Newby-Fraser’s meltdown and comeback to explore the psychological aspect of overtraining (something many high-level, Strava-addicted ultrarunners struggle with).

Newby-Fraser exhibited “maladaptive perfectionism … known to be associated with low self-esteem and insecurity,” Fitzgerald writes. “Athletes who harbor a general feeling that they are never good enough are prone to overtrain in their unending quest to prove their worth. … The coping skill that is required to avoid overtraining is self-trust. An athlete must base her decisions on whether to push or back off on the messages she receives from her own body rather than on what other athletes are doing or on a generalized fear of resting.”

And, since I’m facing my 47th birthday, I also appreciated Fitzgerald’s chapter “Passion Knows No Age” on aging athletes who successfully and happily keep competing. Starting in our mid to late 30s, it’s pretty much guaranteed that we’ll lose both muscle strength and aerobic capacity. “No athlete is exempt from the phenomenon of ‘the last PR,’ but there is a great deal of individual variation in the time course of aging-related athletic decline,” he writes.

What do slower-aging athletes have that others lack? Studies suggest it’s their coping style: “The most successful endurance athletes over the age of 40 are so similar in personality it’s almost uncanny. What we see in all of these men and women is a limitless passion for sport and for the athletic lifestyle that stems from a positive, life-embracing personality.”

If I had one suggestion to make Fitzgerald’s excellent book even better, it would have been to make the analytical sections a little more practical and self-help-ish, and a little less academic, so that athletes and coaches can more easily glean and apply the useful takeaways. For example, I would have liked some sidebars that listed advice or tips in bullet points. But I underlined nearly half the book, an indication of how many points seemed relevant and worth reviewing to help myself and my clients with training and racing.

Finally, I should note that this book is for endurance athletes of all levels, even self-described “waddlers.” To underscore that point, Fitzgerald concludes by highlighting John “The Penguin” Bingham and how he and his slow-running devotees seem like the counterpart to Steve Prefontaine and Pre’s fans. But when Bingham pushes hard and PRs, The Penguin discovers that we all have a bit of Pre’s heart and gutsiness inside us, and we can use our minds—our motivations and coping skills—to tap into that potential for a transformative experience.

I love this paragraph near the end of the chapter on Pre and Bingham, which articulates my best experiences with ultrarunning: “There is no experience quite like that of driving yourself to the point of wanting to give up and then not giving up. In that moment of ‘raw reality,’ as Mark Allen has called it, when something inside you asks, How bad do you want it?, an inner curtain is drawn open, revealing a part of you that is not seen except in moments of crisis. And when your answer is to keep pushing, you come away from the trial with the kind of self-knowledge and self-respect that can’t be bought.”

Update: Listen to the interview Eric and I recorded February 4 with Matt Fitzgerald on UltraRunnerPodcast.

She wanted it bad: Ellie Greenwood tapped motivation to come from behind and close a significant gap to win the 2014 Comrades Marathon. (photo MMPhoto SA via iRunFar.com)

(p.s. Fitzgerald’s book does not spotlight Bitter or Greenwood. I pulled these photos because they stick in my mind as mind-blowing performances that leveraged mental as well as physical fitness.)

Good review. Loving the book as well.

BTW Siri is US.

Great review! Matt Fitzgerald’s thoughts on mental fitness reminds me of something my professor said when I was in med school about cancer patients – a patient’s determination to beat cancer’s ass is as important as the treatments, he NEEDS to be determined to live!

I guess it’s pretty much the same thing as competing and winning a race.

Interesting review, and thoughts. I’m definitely an aging slower runner, and now with the spinal fusion, as I await the green light to run again (now waiting 15 months and counting) I wonder what kind of runner will I be, will what I am able to do satisfy me, will it be fun? And of course, will I be able to qualify for andiron the Comrades? (Love the photo of Greenwood, what an amazing athlete). I’ve been told by my surgeons and coaches that I apparently have amazing strength and dedication, but..I never really thought it much of an advantage. One thing I;ve learned is that having something come hard, really hard… makes the victory much much sweeter than when it only took a bit of regular work. Cheers for your running season!

Hi Sara

At first I thought this post was titled “Mental Illness for Training…” This intrigued me because I write quite a bit about how mental illness can impact and/or improve training. Look around the trail community, plenty of addicts and anxiety sufferers finding a better outlet for their problems.

I disagree with the assertion many runner/writers make that their talent comes from heart, not genetics. It is a common theme in many of the books I read, and it is nonsense. Simply the ability to train over 100 miles per week takes some fortunate genetics. Many of us struggle to get out 25 without injury. Clearly, without “heart” the genetics are probably wasted, so it is really a combination that gets runners to the elite level. I’ve got plenty of heart, I’m just slow as crap.

Thanks for the review, looking forward to the read. -Jeff