(Please read Part 1 for context.)

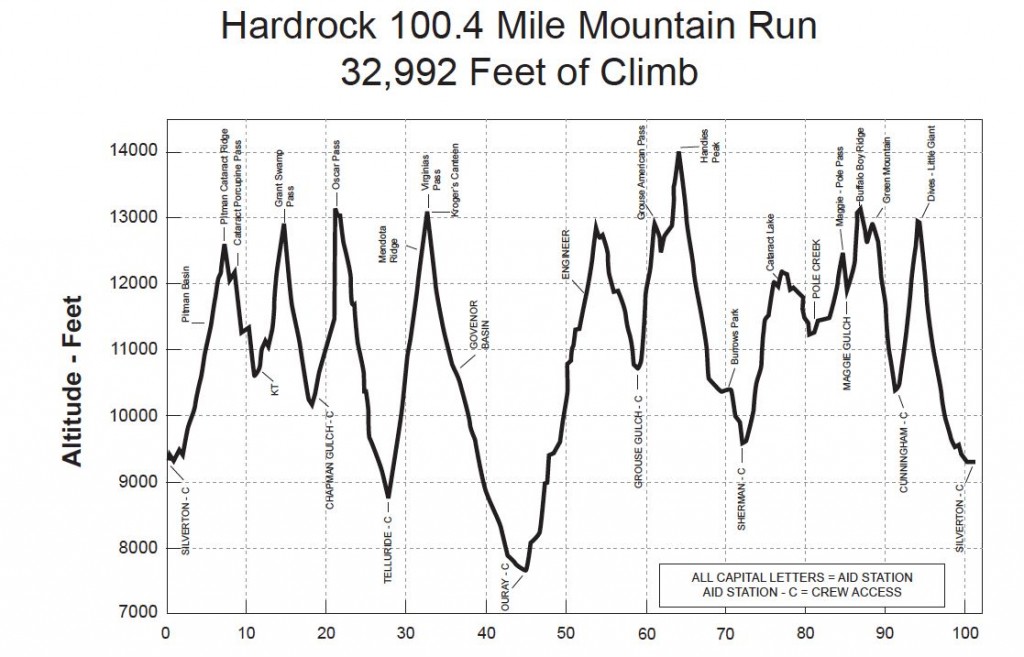

I paced Betsy Nye from Mile 58, the Grouse Gulch Aid Station, to Mile 91, Cunningham (click to enlarge elevation profile).

“I need to go slow,” Betsy said as we exited the Grouse Gulch Aid Station, Mile 58, at almost 3 a.m. She had been on her feet for 21 hours, over five major mountain passes and through two torrential storms.

“Whatever you need,” I said, perfectly content to start hiking at a pace that would take at least 30 minutes per mile. Running at this altitude and slope was out of the question. Even the fastest guys up front mostly hike rather than run up to the summits.

We embarked on switchbacks toward Handies Peak, the highest point (14,048 feet) on the course. The first thing I noticed were the clouds lifting and separating. The storm, which had drenched earlier runners over Handies and made them crouch to avoid lightning, was blowing through. The full moon’s luminescence outlined the clouds with silver linings. I am so lucky—for the weather, and for just being here, I thought.

Next, I noticed the bunches of flowers caught in my headlight’s beam. Bouquets of wild golden daisies burst out of the scree and talus, along with clusters of columbine and sprays of purplish paintbrush. We were above timberline in the alpine tundra, where stubbly green growth clung to the rocky mountainside, partially covered by swaths of snow. Using my headlamp to scan the sides of the trail, I could make out streaks of snow that contrasted with the black of night like the white on the belly of an orca.

Then, I focused on Betsy and noticed her breathing, which sounded rapid and shallow. She paused frequently to try to catch her breath and apologized for struggling. “Don’t apologize, it’s OK,” I said, and then I reminded her to eat.

The job of a pacer at Hardrock is not so much to keep the runner on pace as it is to support the runner mentally and to enhance safety. Pacers for the competitive front-runners may push their runners to go faster, but I would go as slow as Betsy needed. All that mattered, in this race where typically only 70 to 75 percent of the 140 participants finish before the 48-hour cutoff, was getting to the finish line.

What makes Hardrock, nicknamed “Hardwalk,” so slow? A mid-pack Hardrocker, who finishes around 41 hours, averages around a 25 minute/mile pace. For comparison, I can race road 10Ks at a 6:30/mile pace, road marathons at a 7:30 pace and hilly 50-mile trail runs at around a 12 minute/mile pace (5 miles per hour). But at Hardrock, if we could speed up to a 20 minute/mile pace and do 3 miles per hour, that felt fast.

It’s not just the thin air, which makes the heart rate spike. It’s the ever-changing terrain, which includes broken-up rock, boggy mud, slick snow, rushing streams. It’s the skill and care required to spot hard-to-find trail markers when no clear trail is apparent; to step methodically and precisely along the face of a summit while leaning into the angle of repose, fighting off vertigo, knowing that a misstep could send you tumbling.

It’s the need to stop for 20 minutes or longer at aid stations to eat, change out of wet clothes and maybe even take a nap. But mostly, the slow, 48-hour time frame stems from the fact that the course strings together nine or ten mountain passes (depending on how you count them), any one of which by itself would be considered a challenging day-long hike for most regular people.

The trail up Handies peaks at Grouse-American Pass, then traverses a majestic snow-streaked basin before ascending another series of switchbacks to the real summit. The pink glow of sunrise started to break the sky behind the summit as we approached Grouse-American Pass. My feet were soaked from stream crossings, and my upper body was on the verge of chilled. I was glad when Betsy broke into a run on a flatter segment as we crossed the basin so I could warm up my muscles. But she could not sustain running and started hiking again.

Out of the blue she asked, “What are the symptoms of rhabdomyolysis?”

“Why?”

“I just don’t feel right. I’m all puffy.”

Rhabdo—the condition that can lead to kidney failure when overexerted muscle fibers break down too much, too fast and overload the body’s ability to process the waste—is a serious concern and has sent Hardrock women’s champion Diana Finkel to the hospital.

“If your pee is fine, you’ll be fine,” I said as if I knew what I was talking about.

She peed and, indeed, it looked fine and clear.

A little while later, Betsy turned back to me, let down her guard and looked frightened again. This was her 13th Hardrock, and both mentally and physically she had never felt quite so “off.” She was dealing with diarrhea, which could have thrown her body chemistry out of whack, and she felt nauseous but so far hadn’t puked. She asked me, “What if I have hyponatremia?”—a low, diluted level of sodium in the blood that can be caused by over-hydrating.

“You’ll be fine. It’s just the altitude.”

She took a salt pill and resumed her march up the switchbacks.

Hiking behind her, I looked around and tried to suppress my enthusiasm. I didn’t want to annoy Betsy with my cheerfulness, but I couldn’t deny how elated I felt. As the sun rose, orange and pink colored the sky, and to the west, the oversized pale moon set on the horizon. I felt tiny, like an ant climbing a bathtub, but at the same time I felt so high in all senses of the word, to be summiting a 14’er at sunrise.

A view from the top of Handies Peak at sunset courtesy iRunFar’s Facebook album, by Ryan Krol & Liz Sasserman. We saw it some 12 hours later, at sunrise.

On those switchbacks, I discovered that my mismatched trekking poles could be an asset rather than liability. (As detailed in the previous post, due to confusion at the aid station, I ended up with one pole 5 inches longer and heavier than the other.) I kept my hands out of the straps to make it easy to switch the poles from hand to hand, and I kept switching them so that the longer pole was always on the downhill, which made me better balanced as we cut across a hillside.

I had the long pole on the downhill when we broke into a run on one of the flatter traverses of a switchback, and all of a sudden I imagined my dad saying, “You’re a hillside trotter, Sarah,” which made me want to laugh out loud. When I was little, my dad told me a story that Grandpa had told him: that a special breed of Colorado cows, called Hillside Trotters, are born with longer legs on the downhill side so that they don’t tip over on hills. Of course I asked, “But what if they turn around and go the other direction?” He explained that some cows are born to go clockwise, and others counter-clockwise, the same way as people are born left or right handed. Because of this, I carefully studied cows’ legs when I was a kid, not quite believing my dad but intrigued by the possibility that it could be true.

At a slow yet steady pace, we made it to the top of Handies, took in the view—and then Betsy took off.

No matter how tired she is, Betsy is a fast and fearless downhill runner. I suddenly had to shift all my focus to keeping up with her. A gap opened up between us as she let gravity carry her down the hill while she somehow floated above the rocks that took me time to negotiate. I caught up with her as we got down near timberline.

I was roasting in my rain jacket and tights. We both took time to peel off layers and apply sunscreen. I tied my bulky jacket around my waist and did my best to run with it.

The next few hours were a slog. We went down, down, down to the forest, popped out at the Burrow’s Park Aid Station, and then alternately walked and ran a jeep road to Sherman’s. Betsy’s mood lifted and we shared some laughs. I had a delicious piece of pumpkin pie at the Sherman Aid Station, and we headed out for the next big climb.

The beautiful but buggy forest gave way to a wide-open basin, and we noticed clouds gathering for yet another shower. The sky got grayer and grayer exactly in the direction we were heading. I put my jacket back on as rain started to pelt.

I don’t really mind running in rain, but thunder and lightning trigger in me a panicky flight response, and I want to get the hell out of there.

Lightning started flashing closer and closer as we reached a high point near Cataract Lake. I stayed behind Betsy and kept my cool, figuring she had the wisdom and experience to get us through this, so I didn’t really feel scared—until lightning flashed directly overhead, thunder immediately clapped, and Betsy yelled “Fuck!!” and ran harder.

With no time and no place to hunker down, I dashed across the wide-open stretch. It only took a few minutes to reach a place of relative safety, against a hillside where we weren’t the tallest objects that would attract electricity, but it felt like much longer.

And then, just like that, it was over, and we were trudging along again through the spongy, boggy tundra toward Pole Creek. More showers came and went, so we took our jackets off and on, but the sky no longer threatened to zap us.

Betsy and me (behind her in black jacket) descending toward the Pole Creek Aid Station, by Blake Wood who was running behind us.

The next two big climbs, to Maggie-Pole Pass and to Buffalo Boy Ridge, were “only” about 1000 feet each but were so steep over a relatively short distance that our pace resembled videos you see of hikers approaching Everest—step, pause, breathe; step, pause, breathe. The experience renewed my faith that one step in front of the other, no matter how slow, really does count as progress and really will get you there.

All I needed to do, finally, was to get down the mountain—a plummeting, relentless three-mile downhill to the Cunningham Aid Station that I can only describe as so steep. Betsy again seemed to float and fly, giving me my best-ever downhill running lesson. I was close to wiping out on those rocks but managed to keep up.

At the aid station, my job would be done, and Betsy’s friend and crew chief Helen Pelster would accompany Betsy the final 9 miles. I felt torn about ending—relieved, but not wanting it to be over.

The descent into the Cunningham Aid Station–the last hill I ran down. This shows only about a third of the mountainside; the ridge is much higher and farther away. Photo by Jack Meyer

We made it!

Betsy and me after we reached the Cunningham Aid Station, when I finished my pacing duties and she ran the final nine miles with Helen as her pacer.

I had started at 2:50 a.m. and finished at 7:30 p.m.— some 16.5 hours to hike/run a distance a little longer than a 50K, and 50Ks normally take me 5 to 6 hours. I experienced only one-third of Hardrock and can’t help imagining doing the whole thing. It’s exhausting, inspiring, tempting to consider—the stuff that dreams and nightmares are made of.

Who knows if I ever could do it, if I could even gain a spot through the lottery? The odds seem as long as the distance between Hardrock’s first and last climbs.

So I’ll take what I can get—the mini-Hardrock that pacing affords—and be grateful and inspired by the Hardrock veterans like Betsy. I loved being a part of her team.

Betsy far left with her three pacers — Jack, Helen and me — after she kissed the rock at the finish, around 12:30 p.m.

If you want to see what Hardrock is like, this excellent video shot by a Jamil Coury, who shadowed top competitor Timothy Olson, gives glimpses of much of the course. Fast forward to 8:55 to see what Handies looks like in the day time, then watch as Tim goes up it at night. Fast forward again to 13:00 to see the relentless descent into the Cunningham Aid Station.

And if you want to hear even more about the 2014 Hardrock 100, have a listen to this podcast interview with 12th place finisher John Burton, a Hardrock first-timer. I co-hosted the interview with Eric Shranz of UltraRunnerPodcast.com.

I’ll end with a big thank you and congrats to Betsy Nye for letting me play a role in her 13th Hardrock!

All of it brought memories of my pacing duty in 2008, starting at Grouse and to the Rock. That climb to Buffalo Ridge nearly broke me down after running my best friend out of his mind (we even passed Nick and Jamil Coury on the downside of Handies, and Mike was named “Zombie on a leash”). But on Buffalo I died, and I cried…and he had to assure me it will eventually be over:) Thank you for being so generous with your feelings and writings, you did get lucky on those thunderstorms seems like, stories that came from this year’s Handies peak are scary. Betsy, way to get #13!

Such an adventure! I talked to Jack about it a little bit at TRT. Great report. So glad you got to have what sounds like a really incredible experience. To finish 13 of those suckers … Betsy is amazing!

Yes,Betsy is amazing,and according to the Law of Attraction,Like Attracts Like,so you are amazing also Sarah.Great job reporting and pacing,and kudos to Betsy for staying tough,(even though a saboteur pilfered her pacers pole,^^).

Hi, Sarah!

I saved this read for a quiet moment to savor (finally, today…) and it was worth the wait. You so eloquently capture that which I have felt on several pacing occasions: Awe, wonder, inspiration, and guilt for enjoying it so.

And also that question on the runner side: “Am I causing irreversible bodily damage? Do I have Rhamdo symptoms? How much control should I give or take from the central governor?”

Happy Trails & Travels!

H

Hardrock. So awesome, beautiful, relentless. You paced the same section that Jamie paced for me in 2012, and it’s amazing how similar our progress and experiences were through there. Beautiful writing, Sarah! Thanks for sharing your experience, and I’m so glad you had fun!