In February, I intended to peak in training to reach a goal of a PR at the Way Too Cool 50K race on March 9. My plan called for approximately 70 miles per week with back-to-back long trail runs on the weekends, a tempo run with hills on Tuesdays, a speed workout at the track on Thursdays, and three sessions per week of core and strength training. Back in late January, running sub-4:45 at the 50K felt like it mattered, and it motivated me.

Then my mom called from her home, near Tucson, on Monday, Feb. 4. She said Dad, who’s 78, had become so sick overnight with breathing troubles and flu-like symptoms that she drove him to an urgent care place. Doctors there took one look and transferred him by ambulance to the ICU at the main hospital in Tucson.

I was dismayed, but not totally surprised. When I visited in mid-December, my dad was unsteady on his feet, phlegmy in the chest and generally depressed. He struggled to swing a golf club. He had lost so much weight from poor eating, exacerbated by dental problems, that he barely resembled the hearty, pot-bellied person who raised me. He still drank heavily after 5 p.m. and smoked about a pack a day—lifetime habits he never could kick.

The next day, I altered my training plan and met a friend to run 13 miles around the Briones Reservoir in the East Bay. I didn’t think about the pace or mileage as we ran through the oak woodland and green hills. I just vented the mixed feelings I have about my father.

During that run, negativity overshadowed sympathy. I was so angry at him for taking such bad care of himself. I described my dad to my friend as a Jekyll and Hyde who alternated between maudlin and belligerent after his nightly drinks. Running felt like an afterthought to relating the complicated relationship with my mercurial father. But when we reached the end after more than two hours on the trail, I felt more at peace.

I was going to fly to Tucson right away but held off because my brother and sister-in-law were on their way there to support my mom. She was a wreck—weepy, confused, scared. The ICU doctors said Dad had pneumonia, and that his COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) had progressed to emphysema. Since his lungs weren’t working, his heart went into overdrive, with a resting pulse in the 140s to 150s.

This was becoming more serious than any of us expected. Worry and empathy began to dominate my feelings as I realized how scared and helpless he must feel in the hospital. When I ran in the days that followed, I shelved my training plan and ran comfortably, in order to mentally play out different scenarios of how to handle my parents’ situation.

I didn’t think Dad would die anytime soon, but I knew his quality of life would be severely compromised once he got out of the hospital. His health condition also screwed up the plans that he, my mom and my siblings developed to move them to an assisted-living place in Southwestern Colorado—a place my folks liked, and where they’d be close to my brother. The pulmonary specialist said there was no way my dad’s lungs could handle that altitude. We’d have to come up with a different plan for an assisted-care residence.

I told my brother to call me if and when Dad took a turn for the worse and we faced a 50-50 chance or worse of “losing him.” (Phrases like “losing him” or “passing” felt easier to use than “dying.”) My brother made that call to me on Thursday, Feb. 7, and the next afternoon I flew out to be with my folks. The first thing I packed were my running shoes and running clothes, even though I knew I wouldn’t have the opportunity for a long weekend run as planned. I’d be happy with just a short one.

Nothing prepares you for the ICU other than going there and settling in—walking through the warren of windowless hallways, seeing the huddles of worried families, meeting the efficient medical teams. And then, being at the side of the patient, doing whatever you can to make him feel better. You go offline and forget about work. Nothing matters beyond those walls.

Dad was hooked up to a ventilator and heavily sedated by the time I got there, his glasses and clothing removed, looking like a heartbreaking hybrid of an infant and old man. Mom looked stricken. The parent in me took over as I held my mom in my arms and stroked my dad’s forehead. All I wanted was to assure them that it’ll be OK, you’re doing great, I love you and really, it’ll be OK.

Some twelve hours later, I dug my running clothes out of my carry-on bag and changed in the ICU’s bathroom. I assured my mom I’d be back in an hour. I gave the nurses the number to my cell phone, which I carried. And then I took off in the late afternoon, finding a paved bike path along a dry riverbed in downtown Tucson. I had no plan, just the need to break a sweat. I ran hard while playing a slide show in my mind of my dad—of the days when he was so funny and loud that he could get a whole room laughing, the days when we carpooled together to my junior high, the days when he’d throw a Frisbee repeatedly in a game of fetch with his favorite dog.

I re-entered the ICU in my running clothes all sweaty, smelling bad and red-eyed. The huddles of families gave me looks as if I were a freak, as if to ask, “How can you run at a time like this?” To which I would answer, “How could I not?”

The next day, he improved, which felt like emotional whiplash. The doctors said it was time to wean him off the ventilator, and they reduced his sedation so he would be more alert. His eyes opened and showed recognition and longing at me, since the ventilator’s tube prevented him from speaking. He desperately mouthed “water” around the tube. Finally the doctors removed it, and my dad began to breathe on his own and speak in whispers. “I want to die” and “shoot me” were two of his first phrases. My mom and I held his hands and said we loved him and that we wanted him to live, and we promised he would get better. What else could we say?

I drove my mom the half-hour back to her home, and we fell asleep on the night of Sunday, February 10, not knowing what to think or how much optimism to feel. I passed out exhausted and woke up to my cell phone ringing around 5:30 a.m. The caller ID read David G. Lavender—my dad’s name. Somehow he had gotten his cell phone and was well enough to call me.

“Sarah,” his hoarse voice whispered urgently. “Listen. Remember Robert Lewis Stevenson, Kidnapped? I’ve been kidnapped.”

“Dad?”

“Listen, god damn it!” He sounded lucid, like his old self, and angry—but he was talking utter craziness about a “yellow party lounge” upstairs where he had witnessed money laundering and drug dealing, and it was up to me to contact the authorities and get the ransom money together, but I couldn’t let the nurses know because they’re spies and part of the coverup.

My head was spinning. My dad was well enough to carry on a conversation—and he sounded insane. I got him off the phone and called the nurses’ station. They reassured me that he was doing better but experiencing a clinical case of ICU Psychosis, a condition that I learned affects about one in three patients who spend extended time in the ICU. The trauma and disorientation of the setting can provoke extreme paranoia and hallucinations.

My dad was sitting up in bed and eating solid food when my mom and I visited him (it was just me alone with my mom at this point—my other siblings had either returned home or were on their way to join us in Tucson). His vital stats looked stable, so I felt relief that he would recover. But that day turned out to be one of the most upsetting, because he was so disturbed and mad at me for not believing his hallucinations. He kept demanding that I find a Yellow Pages directory or search bizarre terms on Google to prove the conspiracy that he thought he witnessed overnight. My poor mom didn’t know what to say or do to make him feel better, and neither did I. I just knew I had to get him out of the ICU and to a more normal, calming hospital room, so we pressed his doctors to speed up that transfer, which they did.

I snuck away for another run. In the first mile, my muscles felt as stiff and sore as if I had run an ultra the day before. I started at an incredibly slow pace, mentally feeling disoriented and numb. But the rhythm of running oriented and comforted me. Like a massage, it warmed and loosened my muscles. I inhaled the fresh air, squinted in the daylight, lengthened my stride and tried to make sense of all that was happening. It felt like weeks, not days, had passed since Dad became ill and since I had followed my regular routine and training plan. My running had become unstructured and therapeutic.

The next day, as the nurses predicted, he was pretty much back to normal mentally. If anything, he was extra sweet and sensitive. When my mom took his hands, he grasped hers and said, “Forgive me for all our fights.” When I stood by his bedside, he said was so grateful I was there. But I was scheduled to fly back home to California. My other brother had arrived to help out, so I could leave. I promised him I’d return as soon as I could and that I’d help take care of Mom. We told each other “I love you” and said goodbye.

I got back home that Tuesday, February 12, in time to pick up my son from school, take him out for a frozen-yogurt treat to get caught up on what he had been doing while I was gone, and then I headed out for a hard, fast late-afternoon run. It felt like what I call a “detox run” after a night of too much eating or drinking—a run to sweat out all the crap in my system and feel renewed. I ran as if to distance myself from the events of the past five days.

When I returned home and stood stretching in our entranceway around dinnertime, it occurred to me that I should call my dad. He’d be well enough to handle a phone call. So I called his hospital room, and he answered. He sounded tired and resigned to his circumstances, but delighted to hear my voice. I told him about my run and about my son’s first baseball practice of the season, and about my daughter’s involvement in her school’s spring musical—the kinds of details about his grandkids that cheered him up. We each said “I love you,” and I urged him not to worry, just to focus on getting better. I hung up and told my husband, “I just had the nicest and most normal talk with my dad.”

It turned out to be our last conversation. His lung infection spread, and the doctors transferred him back to the ICU. I was at the high school track on Thursday afternoon of Valentine’s Day, getting ready to help coach the middle school’s winter conditioning program, when one of my brothers called me on my cell. They decided, based on the doctors’ prognosis and the do-not-resuscitate instructions in Dad’s health care directive, not to put him back on the ventilator. His lungs were shot, and the focus should shift to palliative care. My brother and sister-in-law in Colorado were rushing back to Arizona to be with him and try to transfer him to hospice. I left the track practice because I didn’t want the kids to see me crying.

I felt the need to run longer the next day, and I took my cell phone to handle calls from my siblings and mom. One call after another came in, so I’d stop my watch, slow my pace to a walk on the trail, and have a surreal conversation about whether Dad was dead or whether, as the nurses suggested, he was stabilizing and might regain consciousness.

My mom was so confused, she thought my dad had already passed away because she had said her big good-bye to him. I gently convinced her to go with my brother back to the hospital in case Dad regained consciousness, because he was still alive and it might be days before he really passes away. She agreed and said she’d meet me at the hospital. Then I had to explain that I was in California, not Tucson, which confused her more. I hung up so upset and confused myself that I intentionally ran deep into the canyon of Redwood Regional Park, out of cell range, to avoid any more calls. I ran for 25 miles, almost five hours.

My other brother and sister-in-law reached Tucson early Friday the 15th and helped transfer Dad to a peaceful, caring hospice facility. My brother called to say that Dad at one point woke up enough to say, “help me,” and at another point whispered, “bourbon.” My siblings, with the wonderful hospice nurses’ help and blessings, soaked an oversized swab in bourbon and put it in his mouth so he could suck on the liquor like a lollipop.

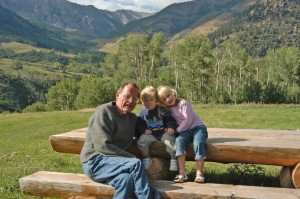

Coincidentally, or serendipitously, our family had planned a weeklong trip to Telluride, Colorado, during our son’s February school break. Telluride—my dad’s second home, the place where he spent so much time and loved—was where he and my mom bought burial plots long ago. Morgan and I decided to go ahead with our trip because chances were we would need to plan a funeral there.

We landed in Montrose, near Telluride, on Saturday, February 16. We drove past Mount Sneffels—the area where we had gone on so many family day trips when I was young—and reached the log cabin on Last Dollar Road that Dad built for us in 1974. Right after we arrived, my brother called to say that Dad had passed away.

Thus began probably the most poignant week of our extended family’s life. In a single week, my other out-of-state siblings and several nieces and nephews traveled to join us. We got Mom, along with Dad’s cremated remains, transferred from Tucson to Telluride. We arranged for a memorial in the church, a reception in the Elks Club afterward, and got an article in the local newspaper about it so his old-time friends could find out and attend the services. I drafted obituaries and a eulogy. Morgan compiled a slide show to play at the reception. My siblings cooked big meals and shoveled snow. We went through several bottles of wine.

And I ran—just an hour or so on most days, through the snow, to say goodbye to my dad, to celebrate the memories we had together in those mountains, and to compose a eulogy in my head.

His services were held at 1 p.m. on Saturday, February 23. On that morning, I made sure to carve out time to run in order to prepare myself mentally for the day. First I ran up toward Bridal Veil Falls, until the snow became so deep that I post-holed past my knees. Then I circled back toward town and decided to go to the cemetery, to make sure the path to his plot had been plowed.

Lone Tree Cemetery in Telluride might be the most beautiful cemetery in the whole world. One summer there long ago, during a 4th of July party in town, Dad and Mom laughed and toasted to the plots they had picked out, and some family members watched the fireworks from there.

I ran through the cemetery and was relieved to see that a path had been cut through the snow to his plot, so I followed it. The path ended where the grave had been dug, and a couple of boards of wood covered it to keep out fresh snow. I knelt and gingerly lifted one of the boards to peer inside.

The hole was so small—only few feet deep and a couple of feet wide—because we planned to bury an urn of his ashes, not a casket. All that was left of my dad—my 6-foot-tall, round, robust, brash, outgoing, irreverent dad—would fit in there. The loss of him hit me harder at that moment than at any other point. I cried more at his burial site when I was there by myself than when we held the services several hours later.

I wanted to personalize those rough boards, so I left a message in the snow when I got up and said goodbye.

The afternoon’s events unfolded beautifully. I was glad I had that emotional release earlier in the day during my run, because it made the church service, burial and reception feel more like a celebration of his life. I felt so much gratitude and love toward my four older siblings. We each turned out so differently, and so scattered geographically, but we came together to take care of our parents.

My brilliant, thoughtful brother David surprised us by bringing a few special items to bury with Dad, to send with his spirit: an Ace and King of Hearts (because Dad loved to gamble at Blackjack), a golf ball, a lavender sachet, a small bit of bourbon, and four dog cookies for four special dogs he lost during his life, whom we hoped he’d meet again.

I ended up wearing my trail-running shoes to the church and burial, since I loaned my snow boots to my mom. It felt comforting to have them on my feet, giving me traction and the feeling that I could start running whenever I wanted or needed.

I’m wearing my Montrail trail-running shoes. We each put a yellow rose in the grave because he gave my mom yellow roses on each of their 55 anniversaries.

One of the many things I’ll miss about my dad is how he read this blog faithfully and emailed supportive comments following each new post. He’d write, “Sarah, this is your best yet!,” which made me laugh, since more often than not he had written the same thing the previous time.

He also followed my races online. Although we occasionally argued over issues involving lifestyles, values, money and family relationships, he was absolutely supportive and excited about my running. He always wanted to know the website of any race I ran and my bib number so he could track me online. He told his golfing friends about my running events. He asked about my mile splits and was curious about what I experienced in different parts of a race. He was a non-runner, yet my biggest fan. Just as he followed the PGA and cheered for certain golfers, so too did he begin to track me and this sport, experiencing enjoyment and escapism through my athletic adventures.

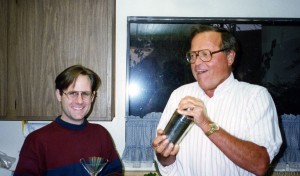

My dad and me in 1996, picnicking on the beach in Carmel right after I ran the Big Sur Marathon. It was the first race he ever watched me run, and he stood near the finish cheering and clapping for me and all the runners. When this photo was taken, we were both looking at the shoreline and watching his dog and my mom play in the water together.

When my dad was in the hospice facility the night before he died, and my two brothers, sister-in-law and mom were at his side, I called my brother David and told him to tell Dad how much I appreciated the way he always read my blog and always supported my running, and that I loved him so much. I heard my brother relay all those words into my dad’s ear. Then my brother told me over the phone that Dad had his eyes closed, but that there was a chance he understood, because he had been responding to some of the conversations and showed some signs of comprehension.

I want to believe that my dad heard my last message. I’ll run the race on March 9 as if he were still tracking me.

***

If you’re curious to read the eulogy, here it is.

Sarah, I loved this post, but I am so sorry to hear about the loss of your dad. He sounded like an amazing man who shaped an incredible legacy. My thoughts are with you and your family!

Sarah – this is incredibly emotional and really captures so much of what you (and all of us) were feeling these last few weeks. I’m so glad your running provided comfort and a bit of normalcy for you. I’m also so glad that you will always be able to run with dad’s support in your head and heart. Thank you for writing this – love you. M.

Sarah, I applaud you for sharing such a personal story and putting into words what many feel about running and life. I will send good mojo to you for March 9th and I imagine it will be a very special day for you.

What a wonderful piece of writing, Sarah. I’m still wiping away the tears myself after reading it. In 2002, my own father passed away. We knew he didn’t have a lot of time left and he had been in and out of the hospital for the couple of weeks previous because of his leukemia. I’d been training for WS that year with AR as a big goal race. My wife and I piled our two daughters in the mini van the morning of AR, we drove from Reno to Sac in the darkness, I ran my fastest AR ever, we waited about five minutes in the Overlook parking lot, piled in the mini van and then drove back to Reno immediately. The next day our family gathered at his bedside and we had ice cream (Dad’s favorite food) together. I’ll always remember how Dad looked around and made meaningful eye contact with all the people that he loved in the world, all sitting around him eating his favorite food together. He looked satisfied, content and, well, ready. It was a moment I’ll always remember. Looking back on it now, I realize I took a huge chance by running AR that weekend. What would’ve happened if Dad had passed while I was out racing? But without that 50-mile run, I know I couldn’t have successfully navigated the days that were to come. I’m so glad to read that your running has helped you through one of the most difficult times the child of a dying parent can ever face. You handled it all with great grace. Good luck to you at Cool. Whatever you run, however you run it on Saturday, it will be a well-deserved effort and finish for you. Time as we measure it through running won’t be nearly as important as the feelings that will be wrapped up in the experience for you on Saturday.

It’s was beautiful in a way pain can be expressed beautifully – I followed your FB updates and felt for you. Running for comfort is what we do when we need one. Thank God we have it. RIP for your Father.

To my wonderful sister: thank you for expressing/sharing/ & caring in your blog that so aptly covered Dad’s last couple of weeks. The peeled emotional layers you stated I think were heart felt by all of us. Run hard, run well on March 9th and know Dad as well as the rest of the Lavender Clan are cheering you onward. Love Ya Sissy!!!!

You are such a gifted runner and writer. I am a fan of yours too! Your dad must have been so proud of you! Thank you for sharing so many of your experiences with us (your fan club). I’ll be tracking you this Saturday too! I think you should still be shooting for the 4:45, for Dad.

Sarah –

I am sorry for your loss and grateful for your generosity in sharing your story. Thank you for this candid and beautiful post.

I will be thinking of you on March 9 and so will all your readers, I am sure.

Your post reminded me that when my dad had his most recent life-threatening health problems, my sanity-saver was running on the treadmill at the Y midway between the hotel and the hospital. I’m sure nonrunners thought it was weird, but runners understand the healing that can come from a run.

I wish you all the healing you need and the peace that will eventually come.

That was really beautiful.Thanks for sharing Sarah.

Beautifully written…I’m so sorry for your loss, and glad that running could be a measure of comfort. Good luck on the 9th!

Sarah,

Your post is amazing. Thank you for sharing such a personal story. It definitely touched me. Thinking of you on March 9th!

Wow. This hit me hard. Thought I was moving past this loss, but the beauty of your words brought it all right back–though thankfully with as much joy as sadness. A wonderful tribute. Thanks.

Thank you for sharing this. This is such a poignant and moving post about the most important things in life.

That was a beautiful piece, Sarah. It made me cry. Your dad was an incredible person, and this was a fitting tribute.

Jenn