One of the things I treasured most about last week’s Grand to Grand Ultra was the social aspect: getting to know others and hearing their stories. This post spotlights a few of those characters and their experiences.

Updated: Here’s my article in Trail Runner that came out in December!) If you’re interested in a race recap, please check out this news article I wrote for Trail Runner’s website right after the race. And if you really want to hear some goofy details about my time on the course, you might enjoy listening to UltraRunnerPodcast.com’s interview with me.

People keep using the word “amazing” to describe my race, to which I want to reply, “It’s really not all that amazing compared to what the others around me did!” Really, there was a blind man from Korea who did the whole course with his guide. Any time I struggled on the trail, I’d tell myself, “The blind guy behind me is getting through this—if he can do it, so can I.” (You can read the story of Kyung Tae and his guide, KiSuk, here on the G2G website).

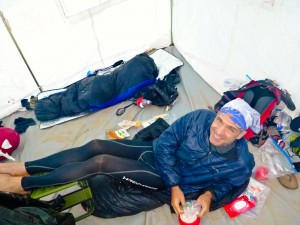

Waking up in Tent #7

At 6 a.m. each morning during the Grand to Grand, a blast of rock music served as the campground’s wake-up call. The first morning, it was the theme from the movie Madagascar, “I Like to Move It, Move It,” and on subsequent mornings, Springsteen and other classic rock hits. I’d sit up in my sleeping bag in our eight-person tent and adjust my eyes to the seven figures lying like larvae in their sleeping bags, surrounded by packs of gear and Ziplocks of food. Our smelly running clothes hung by safety pins from the white canvas tent walls. (We pinned them up in a mostly futile effort to air and dry them out after each day’s run.)

I was assigned to sleep with the same people all week long: Lynne, Dan, Melanie, Jared, Sharon, Stephanie and Stuart. By Day Two, they felt like extended family. I wondered about each one while they were on the course and felt relief when they made it to camp. They saw me in my underwear, and I saw them change their clothes and heard them snore and fart.

Lynne

Lynne, who’s about five years older than I, started taking care of me early in the week when she saw me trying to lance a nasty blister with a dull safety pin and scolded, “What are you doing?! Come here, let me take a look.”

Lynne is an ER trauma nurse originally from Australia, now living in New York City. We hit it off after we discovered that we both consider horses to be our first love. She pulled out a baggie from her pack full of medical instruments, bandages, wipes and pills. She has run other multi-day stage races around the world and had just finished an ultra in the Himalayas a few weeks prior to the Grand to Grand, so she knows precisely what kinds of emergency supplies to bring on these adventures. She doesn’t really train for these runs all over the world—she says that being on her feet all day as a nurse is training enough—she just goes and does them.

I showed her the deformed digit that my pinky toe had become. The whole toe wore the hood of a bulbous blister topped by a callus, and the skin around it looked streaked with red, indicating infection. I knew it could sabotage my ability to run the rest of the week.

“We’re really going to have to go in there,” she said with cheerful determination as she disinfected a pair of surgical scissors and I swabbed my toe with alcohol. Then I surrendered my foot to her, and she pinched the end of my toe and sliced through the skin. “Yes, right, there we go!” As she pinched harder, dark yellow pus oozed out. She cut the hole a little wider. “That’s it!” More than a thimble full of the putrid fluid came out.

If only she could have worked similar magic on her own feet, which were a chaffing, blistering mess beyond repair. Her recent Himalayan adventure damaged the soles and toes, and they didn’t heal properly before the Grand to Grand. By Day Three, the 47-mile long stage, her feet were in such bad shape that she could not tolerate her running shoes.

How do you keep going in a multi-day race if you can’t put on your running shoes? In Lynne’s case, you move on to Plan B without complaining, which meant running and hiking all 47 sandy, hilly miles in toe socks and flip-flops.

The following day, the muscles around her arches were so swollen from gripping the sandal with her first and second toes that she couldn’t wear flip-flops, so she proceeded to Plan C: cutting up her running shoes and using a needle and thread to sew gaiters around them. “I’m not a quitter,” she said while ripping up her shoes, and then she told me about the time she was on the Big Island for the Kona Ironman Championships in 2006, the year a major quake hit the island days before the competition. Lynne was riding her bike at the time, and the earth’s movement shook her off her bike, causing her to crack ribs and injure her knee. She still did the Ironman.

I saw Lynne cross the finish line of Stage 5, the last long stage (25.5 miles) before the final day’s short stage. One foot gave her so much trouble along the way that day that she switched to a flip-flop on only that foot—a shoe on one foot, a sandal on the other. She was laughing at the finish line.

When we traded emails yesterday, she wrote that she was in an airport flying to the Yellowstone-Teton 100-miler, which she’ll run just one week after crossing the Grand to Grand’s finish line.

Dan

Dan, an honest-to-goodness train conductor from Chicago, has big, round cheeks and a mass of thick curls shaped like an afro. If you look at the Grand to Grand’s starting line photo, you’ll see Dan is the guy toward the left in the yellow shirt. And if you look really closely at his water bottle holder on his front pack, you’ll see the top of a beer can that he carried all the way to Camp 1.

Dan didn’t wear a watch, so he was always asking what time it was. Not that it made him hurry knowing we were tight on time before the start. I was in the tent scrambling to get my gear on my back just minutes before the Stage 4 start, wondering how he could be so relaxed when his sleeping bag was still unrolled and his water bottles were empty, when he started waxing nostalgic about his days of go-kart racing and relating go-kart strategy to the kind of stage racing we were doing. I missed the end of his story because I hustled to the starting line. He started several minutes after everyone else had left and didn’t seem to mind.

But Dan’s laid-back demeanor belies a wicked determination. On the very last day’s run—the short 9-miler to the summit at the finish line, through a pine and aspen forest—I glanced over my shoulder on a switchback and was shocked to see Dan right behind me. He was motoring up that dirt road like a monster truck revving out of a mud bog. Dan, man, you can move fast when it counts!

Jared, Sharon, Melanie

Jared and I run a nearly equal pace, but he’s stronger on the technical terrain, so he usually was right ahead of me on the course until I’d pull ahead on the long uphill stretches. (Living in Florida, the poor guy couldn’t get in much hill training.)

He mentioned early on that he has a younger sister named Sara, at which point I began thinking of him as if he were an older brother—someone who’d show me the way and keep me feeling safe on the trail. When I would lie in the tent and develop logorrhea—the affliction of chattiness—he would laugh at my stupid stories while others, in particular Sharon, pulled her sleeping bag over her head and probably wished I’d shut up.

Sharon, who’s British, is a top-ranked ultrarunner internationally. She has run and won crazy ultras all over the world, but perhaps the best clue to her personality is the fact she holds a world record for running 517 miles on a treadmill for seven days. She didn’t look too happy when I caught up to her and passed her on some of the stages. She manages to survive—even thrive—on about 1000 calories a day, and during the day’s run, she’d refuel with only a handful of jellybeans. I wanted to nickname her “Hardtack.”

Sharon, on the left, chasing down Caroline, whom she ultimately beat to win the event. (Photo courtesy of the Grand to Grand.)

But Sharon began to let her hair down, literally and figuratively. She started the week with her hair in tight braids, and as they progressively unraveled, she began to make good-natured fun of her appearance and to chime in more on our conversations. We became friends by week’s end. Before the final day’s run, when she realized that she had the event’s win pretty well locked up based on her cumulative time, she told me, “Maybe it’ll be your turn to win a stage.” She said it with such a warm smile and tone of optimism that I could tell she genuinely wished that for me.

Melanie was the other mom in the tent, and we sometimes wondered aloud about how our spouses and kids were doing without us. I didn’t get to talk to her as much as the others, however, because she tended to be the last in our tent group to reach camp each afternoon or evening. Somehow, in spite of the toll that each day took on us physically, her complexion and hair always looked beautiful. I was struck by the graciousness with which she accepted whichever small rectangle of space had been left for her to unroll her sleeping bag on, even if that plot had a big rock or spiky roots under the ground covering. She never complained about having to dry her clothes by the campfire since the sun had already set, and she shared M&M’s with everyone. She’s the tentmate anyone would be glad to have.

Stephanie and Stuart

Our tent even had a love story. Stephanie, from Canada, and Stuart, from Australia, met each other a few months ago while racing the Gobi March, and they made the Grand to Grand their weeklong date. It was a precious time together for both of them because Stephanie works for the UN in Afghanistan, which makes a trans-continental romance even more precarious.

Stephanie is an incredible ultrarunner, blogger and humanitarian (she ran the Grand to Grand to raise money for a charity called Women for Afghan Women). If she hadn’t been running with her boyfriend and hadn’t suffered a series of mishaps, she probably would have finished at or near the top.

In her race report, she writes, “It was my sixth 250 km self-supported footrace and I thought, hey, what surprises can there possibly be?” Right after the start of Stage 1, she fell and badly banged up her knee, and then later that day, Stuart got terribly sick from dehydration and altitude. You know you’ve crossed a significant threshold in a relationship when one person provides comfort and support when the other is getting sick out of both ends, which is what Stephanie did for Stuart. On Stage 2, they got lost for several miles. On Stage 3, Stephanie developed an agonizing case of butt chafing, which is the ultrarunner’s equivalent of severe diaper rash.

But they made it through with unflagging spirits. Now Stephanie has to return to running circles in an armed compound in Kabul. The next time I inwardly complain about my “boring” running route or start whining about being tired, I’ll think of her and all my tent mates and the Grand to Grand’s other amazing participants who are too numerous to detail.

you did it Sarah! Congratulations – you are just as amazing as any of the characters you wrote of. Well, except maybe for the lady who ran in flipflops.

Can’t wait to read your Trailrunner article!