I arrived at the Telluride Aid Station shortly before midnight to pace my friend Garett Graubins through the final stretch of the Hardrock 100 Mile Endurance Run. He had been running for nearly 18 hours, since 6 a.m. Friday, over eight of the course’s 13 mountain passes. Now he had to struggle over Number 9, one of the most difficult, before meeting me.

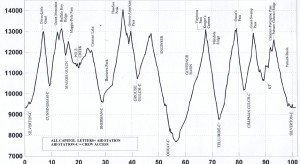

The Hardrock 100 elevation profile: about 68,000 feet total climbing and descent (click to enlarge).

His wife Holly texted me that Garett came through the Ouray Aid Station, at Mile 56, “mentally fried and beat.” She later explained on the phone he was on the verge of dropping out and probably would have if I weren’t waiting for him in Telluride, Mile 73.

Garett had finished ten 100-milers, including two prior Hardrocks, so to say he’s a seasoned ultraunner is an understatement. But on this night he suffered from altitude-induced raspy lungs and an upset stomach. He was off pace to reach his goal of finishing under 32 hours and consequently discouraged that the 2011 Hardrock might be his slowest rather than his fastest. He was enjoying none of it and wanted to be done, period. He had no desire to leave Ouray and climb more than 5000 feet to crest Virginius Pass on treacherous trail, over an icy cornice of snow—all in the dark, all by himself.

“It’s so hard seeing him in that state and sending him off,” Holly said, sounding distressed. “I mean, really, it can’t be healthy, can it?”

I didn’t know what to say, and I felt as guilty as glad that my presence obliged him to continue.

Some friends have complimented me for helping a friend by pacing him to the finish, as though it were generosity that compelled me to go to Colorado for last weekend’s Hardrock 100, which is widely regarded as harder than any in the “grand slam” of 100-mile endurance runs. Truthfully, Garett was the one doing me a favor. He gave me an opportunity to return to my second home of Telluride and experience a slice of an event that I’m not in shape to complete in its entirety. Given my lifelong affinity for Southwestern Colorado and its chunk of the Rockies known as the San Juans, I wanted to explore the peaks I glimpsed as a kid from the back of a truck while 4-wheel driving every summer. And with my running so often focused on speed, I welcomed a challenge where being fast matters hardly at all but being tough means everything.

So I settled in for a long wait at the aid station at Telluride Town Park, reliving in my mind all the great times my husband Morgan and I had in this exact spot over the years: dancing at the Grateful Dead concert in 1987, catching live grasshoppers to hook for bait and fish with our toddlers ten years ago, the kids and our dog skating across the outdoor rink just last Christmas. I sat in the dark of Town Park missing my family intensely and momentarily wondered if I made the right choice to come here without them, to participate in an event that the website repeatedly warns is dangerous.

Garett anticipated he’d reach Telluride between 1:45 and 3 a.m., but by 3 he was just reaching the outpost at the summit above town. At last, at about ten minutes to 5, his bouncing headlamp beam broke the darkness. Then he jogged into view wearing a blank but haunted expression, like someone who walks away from an accident scene unharmed but in shock.

I guided him into a chair and covered him with a borrowed sleeping bag. “I just need some time to gather myself,” he said in a polite, business-like manner, not wanting to talk and shaking his head when offered food. I replenished his water bottles and took care of other matters while trying unsuccessfully to get him to eat. He got up and spent some quality time in the bathroom. Then he returned and said, “I think I just need to close my eyes and take a little nap.”

In the race plan he sent me earlier, he wrote, “beware the chair” and expressed a desire to get in and out of aid stations efficiently. I realized his race plan had been mentally tossed off a cliff somewhere between the 14,048-foot Handies Peak at Mile 36 and Ouray, and now he needed to do whatever necessary to keep from dropping out. So we agreed I’d wake him up in about 10 minutes. He promptly passed out.

Garett resting in Telluride, shortly after 5 a.m. Saturday, 73 miles and almost 24 hours into the Hardrock 100 Endurance Run.

When I woke him up, he seemed a bit refreshed. He started eating pasta and describing how badly he felt after Ouray—never before so mentally low and physically slow. In the background birds started to chirp, signaling morning, and a pinkish light began to illuminate the box canyon’s walls. We wouldn’t need our headlamps after all.

He took his time eating and resting, until at close to 6 he said, “Let’s do it.” Finally, after pulling an all-nighter, I could start.

This year a property dispute forced the race organizers to reroute the course from Bear Creek Canyon to Bridal Veil Basin, which added a couple of miles—how many, no one seemed to know exactly, but I knew we’d have more than the regular 27 miles left until the finish. More like a 50K than a marathon for me. I’m quite familiar with the route up to Bridal Veil Falls and was happy to start up the switchbacks. We hiked rather than ran, but Garett regained some spring in his stride. Daylight—and calories—made all the difference in his mood, and he delighted in the view of Telluride below and the waterfalls above. I played tour guide and told him some of the history of the Pandora Mine and the Powerhouse at the top of the falls.

His spirits got another boost when a runner friend he knows, Billy Simpson of Tennessee, and Billy’s pacer Howie Stern of Mammoth Lakes caught up to us as we took a break. Garett welcomed the companionship, and we climbed the next few miles with those guys toward Hardrock’s peak Number 10: Oscar’s Pass (elev. 13,140).

Upper Bridal Veil Basin is a magnificent amphitheater above timberline where the peaks cradle alpine tundra swathed in snow. We crossed multiple creeks—feet wet, always wet—and I quickly learned to make each step in the snow a little kick to dig in my footing while planting my poles for stability. Nonetheless, I repeatedly slipped and started to slide until those invaluable poles saved me from skidding several hundred feet down.

The course markers—little metallic flags and orange ribbons—always led straight up, always took the toughest route. Billy in his Tennessee twang kept remarking, “A coupla hours, this’ll add two hours, at least! Those back-of-the-packers, they ain’t gonna make the cutoff with this re-route, no way!”

While those men with more than 27 hours and 78 miles on their legs suffered, I had to restrain myself from being annoyingly perky. Three hours into the climb and I felt good, euphoric even. My sea-level lungs and legs performed surprisingly well at nearly 13,000 feet. I wanted to break into a run and bound ahead. I used the excuse of taking photos to run a ways up. We reached the saddle of the ridge that marks Oscar’s Pass, and when I took their photo, they said in unison, “Re-route!”

Oscar’s Pass is notable for two things mainly: the panoramic view of the mountain range that holds Grant-Swamp Pass in the distance—our next climb—and the start of severe switchbacks cut out of busted-up boulders known as talus. It took all my concentration to hopscotch over those rocks without falling, but I kept up and we barreled down, down, down, running hard at times, shuffling painfully at others, until reaching the Chapman Gulch Aid Station around 10:30 a.m.

The following four to five hours over Grant-Swamp Pass and across the Kamm Traverse delivered many extremes, high and low: extreme beauty, altitude, weather and emotion.

Garett’s email signature line includes a quote by Robert Frost: “The best way out is always through.” That saying kept crossing my mind with each unexpected challenge. No doubts expressed, no debates about whether or how to proceed—we’d just go through, or up and over, whatever nature put in our way. Through scratchy willow shrubs that grew out of mud bogs and choked the bottoms of canyons, raking branches across my face while mud oozed up past my ankles. Through miles of jagged talus—chunks of razor-sharp rock ranging in size from a baseball to a basketball—where each wobbly step could twist an ankle. Up a 60-degree slope of small rock called scree that slides underfoot and reduces our forward progress from feet to inches. Down the backside of the Grant-Swamp Pass summit so steep and unstable that my feet slipped out, butt hit hard, and I slid so many breathtaking yards that gritty shards of mountain worked their way into the built-in lining of my shorts until my body, like a falling rock, found an angle of repose. I stood on shaky legs and felt as though I were wearing a diaper packed with dirt.

Standing on top of the Grant-Swamp Pass (elev. 12,920), with the last pitch of scree that we scrambled up on the left side of the photo.

On the ridge of Grant-Swamp Pass, we absorbed the view of gemstone-blue Island Lake, shaped like a giant cloudy eye. The lake gazes back and watches the sky, as if to remind me to look up. I glanced back at Oscar’s Pass and pointed to the storm clouds moving toward us from Telluride. Time to get a move on, to get off this exposed peak before lightening struck.

Clouds above the mountains change from fluffy white to steely gray in less time than it takes to run a mile. The storm hit with full force as we ran along an exposed mountainside trail called the Kamm Traverse. It was the first of two storms to run through—the best way out is always through. Thunder boomed and lightening crackled overhead while the sky dumped soaking rain and then piercing hail, but the lightening flashed in sheets rather than forks, so I figured we’d be OK—small comfort.

At the KT Aid Station, the two of us huddled with about ten others under a tarp and waited out the storm.

We made it to the KT Aid Station (Mile 89 regularly, or about Mile 91 after this year’s rerouting), and we huddled under a tarp strung between two pickup trucks while superhero volunteers dished up soup and patched batteries and cords that fed a computer to transmit information about runners. The lightening started to fork down, and I crouched in a ball of tension waiting for it to zap the radio antennae above the tarp. Twenty minutes later, the storm subsided and blue peeked through the clouds. “Let’s go!” we all said, knowing we had to cross a river below that would swell from the downpour.

The South Fork of Mineral Creek was deep and swift. I watched Garett step in and sink nearly up to his waist as he leaned into the current. I followed behind and used all my core strength and balance to fight back the river that tried to sweep me off my feet. Garett appeared to hold his breath as he watched me from the other side with concern. Wading up the bank, realizing I was safe, I shouted to be heard over the river, “This has been a most unusual day.”

Swarms of mosquitoes and sleep deprivation started to get to Garett—he didn’t complain, but he sagged. We had one last big climb in the final ten miles that we both underestimated. In my mind I saw the elevation chart showing just one hump to “only” 12,500 feet, but it turns out the slog up Cataract-Porcupine Pass and finally Putnam-Cataract Ridge is a three-tiered SOB.

We got up the second tier, ran across a grassy, snow-streaked mesa that shrunk us to the size of ants in a bathtub, and then followed the course-marking flags straight up again. I looked at the sky and figured we had maybe thirty minutes max before another storm hit. At least the footing felt easy—tundra rather than talus—but the climb felt nearly insurmountable. Garett paused almost every minute to cough and catch his breath, his lungs sounding wheezy. I kept going ahead to keep him going.

Garett on the final climb up Putnam, with Grant-Swamp Pass that we crossed several hours earlier in the background.

As a pacer, I discovered a resolve to act outwardly positive no matter what thoughts swirled in my head. Putnam Pass plays tricks with false summits, and just as I’d reach what I thought was the top, I’d take another step and see another hump ahead. I thought, I cannot fucking believe there’s another ridge and this isn’t the summit, but I shouted down to Garett, “Hey, cool! It’s the gift that keeps on giving!”

We made it. We stood on the spine of the final summit. We spun around to survey the miles-wide, mile-high rings of volcanic cratering, tectonic uplift and glacial sculpting that created the San Juans.

I turned away from Garett to start running along the ridge, but he said, “Hey,” and I looked back to see his hand held up. I raised mine too. High-five.

We started to run, really run, slowing only to tiptoe over fragile snow bridges above creeks where the snow had melted in holes halfway across, hinting our bodies could break through if we stepped on a weak spot. No time to linger, storm’s a-comin’.

It hit only a couple of minutes after we left the final aid station, about six miles from the finish. It pelted pea- and marble-sized hail balls so piercing I believe I know what standing in front of a firing squad of BB guns would feel like. Lightening flashed and thunder boomed, splitting the sky directly overhead and ringing in our ears like the crack of a giant sequoia falling. We ran hunched over, across talus on an exposed ledge, and I wondered what would do me in—a bolt of lightening, a broken ankle or a fall into the canyon. The mountain launched rocks without regard for anything below, and one the size of a grapefruit whizzed in front of my face, inches from my nose. We were as drenched as if we had been swimming, and my body began to shake with chills if I stopped, so stopping was not an option.

We reached the canyon bottom and emerged from an aspen grove, two miles from the finish, and confronted a swollen river. I guess the race organizers actually didn’t want us to die because they had strung a rope across. I grabbed that rope and plunged into the river as if it were no big deal, as if I couldn’t get any wetter or colder so who cares about a thigh-high, ice-cold crossing? The raging current grabbed my legs and did its best to suck me downstream, but I gripped the rope and forged ahead as if it were routine.

That’s what Hardrock does to you.

The storm blew through. Silverton sparkled in the distance. Garett, reinvigorated by seeing Holly and his son, Sawyer, at the river, managed to run the entire final stretch and passed others who could barely sustain a shuffle.

I ran with Garett until I peeled off before the finish chute so he could have his moment of running to the finish with his son and partaking in the Hardrock tradition of kissing the painted rock. He finished at just after 7 p.m. in 37 hours, 11 minutes, in 24th place.

Only 80 of the 140 participants finished Hardrock this year (82, if you count the couple that finished a minute after the 48-hour cutoff). But what amazes—and bothers—me is that of the 140, only 16 were women, and only eight of the females finished. Why don’t more women do it? Why don’t I do it?

I think the low number of women has to do with the fact that Hardrock truly is a dangerous course. If a bolt of lightening or a falling rock doesn’t get you, then pulmonary edema, renal failure or a heart attack might. As a mother with two school-age kids at home, I felt pangs of guilt during the riskiest moments of the day that I was jeopardizing my safety when my kids needed me. That reality might scare off a lot of moms with young kids. Plus, you need to train in the environment, which narrows the field to women who live in the Rockies or who have the freedom from work and family to go rent a house in Silverton for a couple of months of training, as some of the hard-core Hardrock dudes (apparently single and childless) did. I could cope with the altitude for those 27-plus miles—though the thin air brought on a throbbing headache in the afternoon that bothered me so much I couldn’t tolerate the feeling of my hat—but anyone who does the full 100 needs to fully acclimate for weeks, preferably months.

When I think about attempting the full Hardrock 100, I realize I’d want my kids to be older and more independent in case something happened to me. I also realize we’d need to be in a phase of life where we could live in Colorado for a few months or longer.

And then I think, I know I’ll want to do something special when I turn 50. This may be just the thing.

One final note: If you like reading stories like this, then I encourage you to read my two favorite historical books that capture adventure in the San Juan Mountains: One Man’s West by my grandfather David S. Lavender, which details his days working in the Camp Bird mine above Ouray during the Depression, and Tomboy Bride by Harriet Fish Backus, the true story of a Victorian-era young mother making a home and raising a baby in the Tomboy Mine encampment above Telluride. Those men and women from a century ago are the genuine bad-asses, the embodiment of endurance. We go to their region for 24 to 48 hours of planned adventure. To us, it’s a sport. To them, it was a hard but necessary way to make a living, a never-ending test of tenacity that made them as tough and weathered as the cabins and barns they built, whose splintered frames still dot the landscape. I appreciate that the Hardrock 100 Endurance Run follows the routes laid out by miners and is dedicated to their memory, carrying on their spirit. We can learn a lot from their example.

I respect the ultrarunners (having done a couple of 50 milers myself), but don’t you have to ask why? The downside to the Hardrocks and the Badwaters is possible sickness or even death…and the upside is what? To prove how tough you are? There’s no physical fitness gain. I don’t mean to be negative – I would love to visit that area and hike it over a week, but especially when you have a family, is the risk worth it?

Hey Phil – I respect and appreciate your comment. To me the upside is the sense of accomplishment, the buildup of stamina and resiliency, the emotional and physical highs (amplified by the lows), and the change in perspective one gains about oneself and the environment. Can you get that from hiking it over 5 to 7 days instead of in 30 to 40 hours? I’m not so sure. Is it worth risk? I’m not so sure either. For 27+ miles in 12 hours, definitely. For 100 miles in up to 48 hours, I can’t decide. And finally, let’s not forget that sickness and death lurk around any corner. If you have a chance, read my prior blog post that spotlights my great uncle and his untimely death. If I were him, I’d be glad I took all those risks in the San Juans before dying of disease.

For Sarah and from one non-ultra Phil to the Ultra Phil raising the safety question…I don’t have any answers, only an appreciation for the amazing feats us mortals get to read about. Seems to me that everyone must make their own decision and has the absolute right to do so. That being said….Sarah, I pray for your good health and safety no matter what you do.

Wonderful adventure, and great report. I don’t think you hit why there aren’t more women in the race. There are plenty of flatlanders who run successfully, and plenty of fathers with children who have similar concerns as mothers with children, especially if they are the breadwinners. I won’t pretend to have the answer. Like UTMB, Hardrock would benefit from more women runners. I hope the women in our sport will grasp the challenge of the San Juans.

Congrats to Garett, and to you Sarah, for living life fully. It’s the best we can provide for our children.

Perceptive and well-put points as always, Sam. Thanks! So, what about you–do you want to do HR100 now?

What do I do? I wondered if you were going to take the plunge, if not next year, some time soon.

It’s on my list. I think the next year or two might be difficult, and I have other challenges to take on.

Thanks again for your pictures and report.

Great Report! I enjoyed running/ climbing, and crawling along with you guys on that stretch above Bridal Veil.

Remember this about the number of women. Hardrock is a lottery system. Many, many women apply, but the luck of the draw is the final determining factor in the number that start on race day…

Take care,

Howie

Good to meet you, too, Howie, and I’ll try to look you up the next time we’re in Mammoth (we’ll be there in mid August and over the holidays most likely). As for the women … I don’t know, it’s still a mystery to me. Jeffrey Rogers’ point above is a good one. I took a look at the 2010 results and counted 16 female entrants with 11 finishing. For 2009 it was 22 women entrants and 18 finishers. 2008: 17 women entrants, 10 finishers. Seems to me pretty lopsided.

Sarah, we came so close to meeting face to face! I was in Ouray/Silverton this weekened and saw Garett at Ouray with Holly Friday night. He did seem rather rough, was still chatty and smiling, amazingly! Thanks for sharing your experience of pacing at Hardrock–after running up to Grant-Swamp pass on Sunday (after the race had finished) I decided that I’d have to come back and pace someone next year. Running this race and in those mountain makes me feel alive like nothing else!

I’m not sure many ultras of 50 miles or more exist that have a 50/50 split of men and women. I really think a lot of it has to do with the fact that we are really not so far from when women did not do sports– pre-Title IX and all. I think that couples still tend to split along gender lines (big generalization here, as I’m definitely not giving up my running time and I do know many other women who run as well– like you, Sarah) where the “sport time” is generally given to the male in the couple. I think that as the years pass, we are going to see things change, but we are not so far out of “women don’t run long distances” mentality. If you’re looking for a really interesting person to talk to about her experience as a woman in long-distance running over the years, talk to Doone Watson.

There’s a lot of truth in this. It takes time before people’s expectations – of what they can do and what their spouse can do – change. Women are still relatively new at this long-distance running thing.

Sarah,

What a terrific post. Having heard bits and pieces of this, it was fun to get such a comprehensive, chronological account of the race. I love the cognitive dissonance created by the way the grueling report is belied by the fact that you are smiling in all those pictures (someone was having fun!). So proud of you, and so glad you had such a profound (and safe) experience. Bummer that Karen and I weren’t able to cheer you and Garret on as you passed through Ice Lake basin (but thanks for providing the excuse for such a lovely overnight). While I clearly will never run (or pace) this race, you’ve managed to get me hooked nonetheless. Maybe next spring I’ll look into volunteering with the marking team or with one of the aid stations. What a blessing it is to spend time in this landscape!

Wow!!! Great write-up. I read Tomboy Bride after we stayed in Telluride last summer. I would LOVE to do this run, but, the reality of having two young children is an issue. Thanks for the very real story.

Wonderful write-up, Sarah, and great pictures. Morgan’s not the only photographer in the family! You got to experience a large chunk of course many of us will never see. (I, at least, am too chicken!)

Before you do Hardrock, though, how about we get you in another 100 first? You will need one as a qualifier, after all. 🙂 I’m really hoping/planning to run Leadville soon – 2012 or 2013. Maybe you can join me – it’ll be like the lite beer version of HR100!

Lovely write-up, Sarah. I hope you’re recovering well. Nice to see you out here, too!

I wondered on same topic of female number at HR, or ultras in general. While many fathers are bread winners, women are traditionally the child-caring (and rearing) members. May be I am too traditional, but the world hasn’t changed yet (actually, I don’t even want it to). I just wish somehow we get more hours a day:) Training takes time. Many men despise women doing well in (extreme) sports while liking them looking good. Kids need to be shuttled, fed, checked on, dinners made, husbands tended to…For the last 10 years I’ve been doing it and squeezing every minute out of the day. I also had applied to HR 4 times (and got in/finished once). I’ll keep applying, and I’ll keep ultrarunning and doing other challenges. But then again, by now my kids are grown, and my finances are stable.

As for Garett – great job! What a day. I swept some course and spent 10 days in San Juan. Best place on Earth. See you there next year.

Beautiful write-up, Sarah! It was quite an experience, wasn’t it? Sorry we didn’t run into each other out there.

I would have to agree with other commenters that the lack of women is more about societal expectations than anything else, although I’m sure there are many factors. All ultras have many more men than women on the start list, not just “extreme” ones like Hardrock. Also, it could just be that women are smarter than men, because you have to be CRAZY to be a Hardrocker. 😉

Sarah,

Thanks for the great write-up. I have an obsession with HR100. Like you, the San Juans are very special to me. I spent my childhood summers in the La Platas between Mancos and Durango (but never climbed Lavender peak). I have had MANY close calls with lightning. I have read all of the race reports and find them absolutely fascinating. I hope to aid at the race next year when our finances are better. I wish I could pace. However, all the training in the world can’t overcome some physical issues. I’ll have to be content to run my few measley miles here in Eugene OR.

Here’s another theory on why fewer women runners: women have a greater Q-angle (from hips down to knees)compared to men which can lead to a predisposition toward knee issues. I see this with female patients that I treat. Also, if one has given birth, she would have gone through a period of hormone induced ligamentous laxity that could lead to some SI joint and L5/S1 issues. This is based on my experience as a physical therapist.

…Or as my friend Heike believes (who is the most amazing female runner/athelete I have personally known) – she just thinks it’s crazy to put one’s body through such an ordeal.

My obsession with the race continues and it is not for me to question people’s motivation. I hope to be their next year to help participants stay safe and healthy. I look forward to meeting all of the HR100 family.

Maybe women are slightly more sensible than men. 🙂 Blake Wood wrote an essay many years ago to explain that men do ultras out of childbirth envy… so that leaves a big question mark over women. I haven’t had kids so maybe I’m in the same boat as the guys. 🙂

This year 19 women started and 13 finished, slightly worse percentage than overall, which was 74% finishing. I was one of the 6 who dropped, and I never had any doubt I *could* finish, I just wimped out at a low mental point. It happens. I’ll be back for finish #3.