At 6 a.m. this morning—Friday, July 8, 2011—some 140 runners started the extreme event known as the 100-mile Hardrock Endurance Run through the San Juan Mountains of Southwestern Colorado. And sometime after midnight tonight, probably close to 2 a.m., I’ll join one of them, Garett Graubins, in Telluride at Mile 73. Together, we’ll alternately run and hike the remaining portion to the finish line in Silverton.

I’m running and hiking only slightly more than one-quarter of the race course—hardly more than a marathon—and yet it may be the most challenging thing I’ve ever done. I am in awe of those who do the full course.

Some facts about the Hardrock 100:

- The elevation ranges from a low of 7680 to a high of 14,048 feet.

- It crosses 13 mountain peaks in a loop through the historic mining towns of Silverton, Lake City, Ouray and Telluride.

- The total accumulated vertical climb and descent, over 13 mountain peaks, is about 66,000 feet.

- The course record, held by Kyle Skaggs, is 23 hours, 23 minutes. By comparison, the course record at the Western States 100, held by Geoff Roes, is 15 hours, 7 minutes. In other words, Hardrock is much harder than other 100-milers!

The runner’s manual states: “This is a dangerous course! In addition to trail running, you will do some mild rock climbing (hands required), wade ice cold streams, struggle through snow which at night and in the early morning will be rock hard and slick and during the heat of the day will be so soft you can sink to your knees and above, cross cliffs where a fall could send you 300 feet straight down, use fixed ropes as handrails, and be expected to negotiate the course with or without markers.”

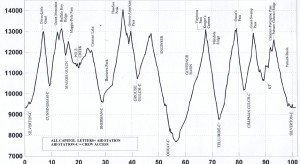

The Hardrock 100 elevation profile (click to enlarge). I meet Garett and start running at the Telluride aid station.

I arrived here Wednesday afternoon but haven’t mustered the ability to write about the destination or the event. It’s partly because this corner of Colorado, where I spent so much of my childhood and now consider it a second home, stirs up so much internally that I’m not in a place mentally just yet to adequately describe it.

But mostly I’m overwhelmed by this Hardrock event and have used every spare moment to study it as though cramming for a test. I’m squinting at topo maps, digesting race reports from past years, and re-reading books on the region’s history and geology written by my grandfather, who was born and raised here and worked as a miner and rancher in the 1930s. I’m determined not to let Garett down as a pacer, and I want to appreciate and understand the course as much as possible.

I ran a portion of the course above Telluride yesterday morning to acclimate and see the part I’ll have to run in the dark. This year, the course has been re-routed after Telluride due to a property dispute on the stretch by Telluride where it normally runs, so the course is actually longer after Telluride–by how much, I’m not sure. This year we’ll go up past Bridal Veil Falls behind town. Ever since I was a kid, I viewed those switchbacks to the left of the falls as a major day hike. Tonight, it’ll be a gentle warm-up for what lies ahead!

Looking up at the first few miles we'll run after leaving the Telluride Aid Station past Bridal Veil Falls.

I hope to capture the experience in a post-race recap. For now, I’ll simply run some photos and captions (click on the photos to enlarge them). For a great overview of the course, read Garett’s report from last year. However, keep in mind that last year the runners covered the course in the opposite direction. The race alternates directions annually, and this year the loop is counterclockwise. Also, today you can follow the race live on iRunFar.com and on the official website.

This is looking back at the San Sophia Ridge above Telluride. Garett and other runners will traverse treacherous single track up there before dropping into Telluride.

I will reach this saddle near Upper Bridal Veil Basin, about 7 miles above Telluride, when it's still dark out. I'll have one headlamp on my forehead and another around my waist to light the way.

Grant Pass, around Mile 85, is a mass of scree and snow. The runner's manual describes it as "loose rock and dirt on a very steep mountainside that has enough friction to stay where it is until you step on it, and then it slides down the hill. Like trying to go uphill in mashed potatoes, you slide back 3/4 of a step for each step up." (photo courtesy Steve Pero and the HR trail marking crew)

Island Lake, on the back side of Grant-Swamp pass, where we'll come down. This photo was taken about two weeks ago, so the snow has melted somewhat ... but I still expect a lot of snowy, icy butt-sliding. (Photo courtesy Steve Pero.)

Compare the photo above with this one of Island Lake from Garett's 2010 race report. Yes, there's a lot more snow this year!

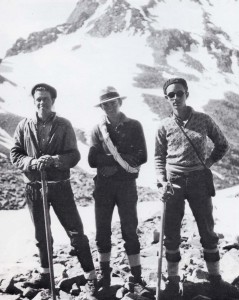

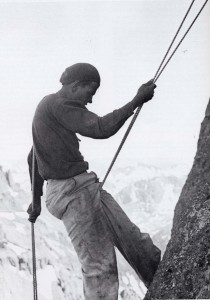

The Hardrock 100 runner’s manual states: “This route follows routes laid out by the miners and is dedicated to their memory.” I take that dedication to heart and will conjure the memory of one person in particular: my great-uncle Dwight G. Lavender, my grandfather’s younger brother. He and my grandpa spent their early years in Telluride and returned as young adults. While my grandfather got a job in the Camp Bird Mine above Ouray during the Depression (an experience magnificently recounted in his book One Man’s West), Dwight made a name for himself as a pioneering mountain climber and founding member of the San Juan Mountaineers. From 1929 – 1932, he and his buddies climbed, measured and carefully documented virtually all of the major peaks in the San Juans and many of the minor peaks.

Dwight Lavender on the left with his friends Chester Price and Forrest Greenfield in 1930 after a successful ascent of El Diente (14,159 feet). Dwight and Chester organized the San Juan Mountaineers.

As recounted in Mel Griffiths’ book San Juan Country (published 1984 and out of print but well worth the effort to find it used), “By the fall of 1932, Dwight had visited and climbed in almost all parts of the San Juans and had gathered enough material to provide the information base for a ‘guidebook.’ With characteristic energy, Dwight did not wait to find a publisher for his work; he forged ahead on his own.” He typed and assembled illustrations and photos for a thick volume called San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado that was reproduced into four or five carbon copies, one of which is somewhere in my family’s archives, and I’m determined to get it digitized for a new generation. (I’m also determined to climb Lavender Peak in the La Plata Range, named in honor of Dwight, sometime in my life.)

I was close to my grandfather but never met his younger brother. When Dwight entered graduate school at Stanford, at age 23, he contracted polio and died in a matter of months. He’s always loomed large in my mind as a hero who died before his time–a reminder to live life to the fullest as though each day could be your last.

Gazing at photos and text about my grandfather and his brother—and my grandmother, reputedly the first white woman to summit the Snefflels range near Telluride in the 1930s—I am emboldened to push myself beyond limits, cope with discomfort and explore new territory. If they can scramble up peaks and tunnel into mines with their rudimentary equipment and with little to guide them but their spirit, then I certainly can make my way over these mountain passes fortified with aid stations, modern gear and course markings along the way.

I can’t wait for the clock to hit midnight and to head to town to start this marathon.

Good luck tonight. This is an impressive race. Thanks for including all these historical facts and your family history! Your pictures bring back the memory of my runs in Colorado ( the Mosquito marathon in Leadville).

Isn’t this the race, that is not a race?

Correct, it is not a “race” in the regular sense, that’s for sure! It is a test of individual endurance against the landscape. The nickname is “hard walk” because so much of it is not runnable.

Sarah, I’m so impressed with what you are about to attempt. I can’t wait to hear about your experience. Good luck to you and all the others making this journey.

Sarah,

I will be thinking of you tonight and know that you have the “right stuff” to accomplish your goal. Can’t wait to hear your stories when you get back. Good luck!

Len

That was amazing to read. I didn’t realize all of that – I can’t wait to hear about it. Good luck and bring back good tales. Again – you impress and inspire.

Sarah,

Great Hardrock stories. I don’t know Garett, but I ran into him a few times on the Boulder trails last year as we were both training for Hardrock. Sounds like he chose a great pacer this year. Neat that you could share stories about the various features on the course given your familiarity with the area and your family history.

Very cool that your family has an original copy of The San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado. I used to spend time in the American Alpine Club library in Golden poring over a copy that they had. The Colorado Mountain Club Press re-published the guide a few years ago, so I’m thrilled to have my own copy now. Even more thrilling, though, was finding your great-uncle’s original signature in a summit register in the San Juans a few years ago.

I believe some of your grandfather’s (and great-uncle’s?) items ended up in the CU library archives. A friend who works at the library invited me over to take a look, but I never did take advantage of that opportunity.

John