New and not-so-new challenges loom on the horizon for me as an ultrarunner, such as running part of the Hardrock 100 as a pacer and aiming for a PR in a 50K later this year. I also struggle with ambivalence about graduating to the 100-mile distance.

Having run two 50Ms and lots of 50Ks, should I double my distance to achieve the highest rank to which any ultrarunner inevitably aspires? Would I gain some higher level of fitness and enlightenment about life in the process? Is it worth siphoning off time and energy that I might otherwise spend on my family? And how can I counter my husband’s persuasive argument that training for a 100-miler might do more harm than good to my health and wellness?

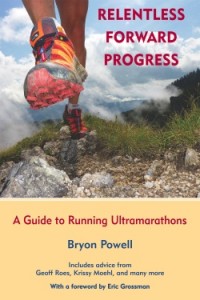

With those questions in mind, I eagerly dug into the new book Relentless Forward Progress: A Guide to Running Ultramarathons by iRunFar‘s Bryon Powell.

I also picked up the book eager to learn more about Bryon, whose blog I read faithfully. For those of you unfamiliar with him and his site iRunFar.com, he has established himself as one of the best, most thorough journalists and evangelists of the sport. He provides comprehensive coverage of high-stakes races, publishes spot-on gear reviews, and writes colorful race reports that capture the spirit and scene of the ultra/trail-running community. Having had the pleasure of meeting him a couple of times, I looked forward to learning more about what makes him tick.

The point of that preface is to show that I was carrying a lot of baggage when I picked up Relentless Forward Progress and had high expectations for it.

That said, I definitely can recommend this book to runners who are passionate about training and racing at marathon-or-shorter distances and who, for whatever reason, caught the bug that makes them want to cross over to ultra territory. Relentless Forward Progress provides a thorough and prudent overview of the building blocks to becoming an ultrarunner and strategies for success on race day.

Bryon starts with advice on how to safely increase training volume, how to train on trail, and how to use his weekly training plans to bump up to 50K, 50M and longer distances on relatively low mileage (peaking at 50 miles/week) or somewhat higher mileage (70 miles/week). He also covers the nuts and bolts of fueling, gearing, acclimating, pacing and racing.

Along the way, I gleaned numerous tips that fall into the “Great idea! Never thought of that” category, such as this one: “If, when planning a B2B (back to back), you decide to run one hillier route, such as on mountain trails that will require intermittent hiking, and one entirely runnable effort, schedule the runnable session first. You will have no problem walking up steep climbs and rolling down hills on road-deadened legs, but you aren’t very likely to enjoy running for hours straight with an unchanging gait on already tired legs.” Or this one: “To control my pace in the first half of an ultra, when I’m X miles from the start, I consider whether I’ll be able to maintain that same effort X miles from the finish.”

Several notable ultrarunners enhance the chapters with essays that share advice on specific topics, and these contributors provide some of the book’s highlights. One that stands out with great voice and advice is Dave Mackey’s on downhill running (I love this line: “Like the engineer at the cocktail party trying to get a date, staring at your feet will mean social or, in this case, running collapse”). Another is Eric Grossman’s account on “in-race management,” otherwise known reaching the edge of a bonk midway through an ultra and then carefully managing hydration and fueling to back away from the brink. Grossman’s gripping narrative of confronting the “demons of races past” transports the reader to the scene on the trail and captures the essence of the sport.

Bryon Powell doing his thing (images courtesy iRunFar.com).

The chapters also snap to life whenever Bryon injects anecdotes of his own, as in the chapter on fueling when he answers the question “So how much should you eat during an ultra?” with very specific details of what works for him, or in the section on extreme weather where he describes his brush with heat exhaustion during a double crossing of the Grand Canyon.

Given Bryon’s experience as a runner/coach, his talent as a writer and his likable personality, I only wish he had injected his own anecdotes and attitude into the book even more. Mostly, though, I wish the book spent a little more time delving into the why of ultrarunning—especially the why behind 24-plus-hour 100-milers—along with a larger dose of mental tricks and soul-inspiring stories to sustain the training and race-day effort.

Does the book reveal how to run 100? Yes—but I’m still on the fence about whether to attempt that lofty goal.

Setting aside my personal hangups, I’m grateful that Relentless Forward Progress provided specific advice that will help me reach upcoming goals at shorter distances and in high altitude. Likewise, countless runners surely will hit the trail and achieve their ultra-distance goals thanks to this book’s wisdom. For that and more, we can thank Bryon Powell for making a significant contribution to the literature of ultrarunning.

Sounds like a book I’d like to read! I’d like to run 100-mile races someday. I’ve read a bunch of race reports from Scott Dunlap, Mark Tanaka, Jean Pommier and so many other blogging ultra runners, and they all have that adventurous feel to them. It captures my imagination, and it allows me to dream a little about reaching for something so surreal. And I think you could run 100 miles so much better than most of us. Heck, you torch most of us in the 50 Mile races! And I think you could get away with it with the training you already are doing. Training for 100 Mile races doesn’t mean you have to double your 50-mile training, in my opinion that is.

Anyway, thanks for the book review! I’ll definitely have to get this book.

This is a great review. I bought the book based on this and you are spot on. Bryon does a really good job explaining the training systems and programs, it really helped me to prepare for my first ultra.