I consider myself a capable trail runner — in California, that is. In Colorado, no way.

I’ve been in Telluride, Colorado, a little over a week, adjusting to life away from home and acclimating in the high altitude for the September 12 Imogene Pass Run. (Our family travel blog away-together.com details why we’re here and what we’re doing.)

If you’ve never been to Telluride, picture a cluster of brightly painted Victorian-era houses and frontier-era storefronts lining main street, all dwarfed by the surrounding mountains. The town sits at 8750 feet in a horseshoe-shaped bend in the San Juan Mountain range, and the road to town dead ends where the peaks rise up almost 5000 feet more and waterfalls cascade down. Spruce and aspen blanket the backdrop, and hunks of red rocks jut out most of the way up. Then the trees thin out and the red rocks turn a smoother gray on the peaks and ridges, which are stained by rust-colored splotches of mineral deposits that lured prospectors in the 1870s.

If you could look right over the mountain behind Telluride or tunnel through it, you’d reach another old mining town, Ouray, also tucked in a box canyon of stunning scenery. Connecting the two towns is a single-lane rocky road: Imogene Pass. It used to be the trail leading to large-scale mining operations where thousands of people worked from the late 1800s through the Depression. The road runs past the ghost towns of Tomboy on the Telluride side and Camp Bird on the Ouray side, and it crests above timberline at 13,114 feet.

I have some history with Imogene Pass, even though I’ve never run it. I’m here training for the race in part because the trek over the road always stood in my mind as an extreme daytrip infused with family folklore.

This picture of our family Bronco on Imogene was taken around 1970, when I would have been a baby. My siblings are in the truck cab; I'm not sure if I was there, too, but if I was then it may have been my first time over Imogene.

When I was growing up and spending every summer here, my dad would drive the family over Imogene in a 4-wheel-drive Bronco or, later on, in a Chevy truck we called Big Red. My siblings and I would pile into the open truck bed, which was padded with a mattress, and hang on to the rim as Dad shifted to low gear and climbed the treacherous grade. When a Jeep approached in the opposite direction, Dad would drive the truck onto the uphill embankment, at a 45-degree angle, so the other vehicle had just a hair’s width to pass. Mom sometimes got out to hike and audibly recited the Lord’s Prayer because she was so terrified the truck would roll over and down the canyon.

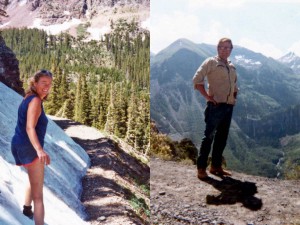

My mom and dad, circa 1975, on one of our daytrips over Imogene Pass. They would have been about 40, the age I am now.

Along the way and over the years I caught fragments of family history involving Imogene Pass and my grandfather, David S. Lavender, who in the 1930s went to work as a hoist operator deep underground in Camp Bird, which is Mile 5 on the Imogene Pass Run. He went to his first day of work by hiring a horse in Ouray and riding through a snowstorm to reach the encampment (chronicled in the first chapter of One Man’s West, his memoir of mining and ranching in the region). His wife, my grandmother Brookie, left a blue-blooded New York lifestyle to join him and adapted to Colorado so well that she reputedly became the first woman (or at least, the first white woman) to climb nearby Mount Sneffels. His brother, Dwight, had a peak named after him because he scaled several of the state’s “fourteeners” in the late 1920s and wrote the San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado in the early ’30s.

And then there’s Grandpa’s stepfather, Ed Lavender, who ran a mule train from Telluride to Tomboy to deliver mail and supplies. When gunfights between union workers and “scabs” broke out around the mines a century ago, someone killed someone else near Imogene Pass and Ed was asked to haul the body back to town. The story goes that he was concerned he didn’t have authority to transport a dead man, but he did have authority to transport mail, so he stuffed the body in a mail sack (or, in another version of the tale, stuck a postage stamp on the body’s forehead) before leading it down the mountain on a mule.

I can’t vouch for the veracity of these stories, but I can say they inspired me — haunted me — as I started up toward Imogene from the Telluride side a couple of days ago. I wanted to get acquainted with this trail not as a kid or a tourist but, for the first time, as a runner.

Running in this scenery and altitude literally is breathtaking. I planned to run from town just five miles up to Tomboy, at 11,400 feet, but quickly downshifted to a jog/walk pattern of jogging for three or four minutes, then walking nearly as long to catch my breath. I felt like an utter beginner as a runner, needing numerous breaks. My pace averaged around 15 minutes per mile. I stopped often not only to catch my breath, but also to take in the views, because while running (or walking) I kept my eyes down and fully concentrated on the footing. Many stretches are nothing but busted-up boulders, creating a loose gravel where the smallest rocks are the size of a fist and the larger ones are as big as a head.

I made it to Tomboy and lifted my eyes to look up at the Imogene Pass summit, which was still two miles and 1700 feet higher. Exhausted, I felt a twinge of self-pity until I gazed at the rotting, sagging frames of the century-old buildings and tried to imagine workers and their families carving out a living in such a harsh environment, where lightening, hail or snow sneak up most afternoons. The memoir Tomboy Bride by Harriet Fish Backus sticks in my mind as an unforgettable account of life up here. Those families toiled on this mountain to earn a wage, whereas I try to run up here for an hour or so merely for exercise and a taste of adventure. My little jaunt seemed pretty easy by comparison.

A snapshot from my parents' album showing Tomboy Mines in the 1970s, with the 13,114-foot Imogene Pass summit in the background.

Every day now, when I drive into town, I look at that summit where Imogene Pass runs and think, in my 11-year-old’s lingo, O-M-G. In a couple of weeks I have to cross that ridge behind town, from Ouray to Telluride, on my own two legs. It’s only 17 miles, but I’m scared. I’m scared I’ll be dizzy with lightheadedness, or twist my ankle and fall, or get caught in a lightening storm, or all of the above. Or — worst of all — that I might drop out before the finish.

Trying to run in this thin air and terrain has enhanced my respect not only for Colorado trail runners, but also for my ancestors and their peers. I truly am humbled. I also can’t help but think about how the hardy generations before me weakened and weathered over time, like all those wooden structures that splinter and sag along Imogene Pass. Someday, when my kids reach my age, I may find myself too weak to stand tall and hike high, and I bet I’ll look back fondly on running this road no matter how tough I find it now.

SARAH, THIS IS TERRIFIC! I WILL NEVER FORGET MY TRIP OVER THE PASS WITH YOUR GRANDPA. YOUR DAD WAS AT THE WHEEL OF THE BRONCO. WHEN WE CAME OVER THE TOP I LOOKED DOWN AND BASED ON THE DESCRIPTION IN ONE MAN’S WEST I KNEW I WAS LOOKING A CAMP BIRD. YOUR MOM MET US WITH A PICNIC LUNCH DOWN THE ROAD AND WE SAT TO EAT ON A CARPET OF WILD FLOWERS TO THE MUSIC OF WATER AND BIRDSONG. I AM OVERWHELMED BY THE MEMORY EVEN TO THIS DAY. MORE LATER, MURIEL

I well remember many trips up and over Imogene and spending time at both Tomboy and the Camp Bird with you and your family ‘back in the day’…I will be thinking of you on the 12th and awaiting the report. I loved this entry, Sarah, and am humbled just thinking of you making the attempt. How I loved hearing your grandfather tell stories of his days at The Camp Bird and mining those mountains. Such a legacy!

Sarah,

You’re such an amazing and gifted writer/blogger. Reading your blogs is like taking a journey with you; such a trip! Thanks for sharing.

So the question is… will you run Leadville or Pikes Peak marathons/ultras someday? 😉

Thomas