This is a story I wrote for Trail Runner; the version below has some extra photos and a Q&A section at the end with commentary.

Morgan, Kyle and me the weekend of March 14-15 in Boulder, in Chautauqua Park, when we packed him up and moved him home.

March 15, the second Sunday of the month, I wake early in a hotel room in Boulder to run in Chautauqua Park. Pink light illuminates the massive rock formations of the Flatirons, but I barely notice the view. I am so wound up with worry that I see only mental images that flip like flashcards, each involving a family member, every thought layered with news of the pandemic.

I picture my son’s dorm room that we need to pack up this morning so we can move him back home. At least he’s with us now, but my daughter needs to get back from Rhode Island. She is struggling to vacate her apartment and catch a flight. Her senior year in college is ending abruptly—how can this be? She’s prone to recurrent infections that need medicine. What if she catches this virus?

Client work for my husband’s business abruptly dried up. He has enough in the bank to make today’s payroll, but how will he pay the staff in the coming weeks? It scares me to see his face so grim as he toggles his screen between QuickBooks and CNN. The market surely will tank when it opens tomorrow. The ski resort closed yesterday. So many friends out of work.

As I run, I feel yesterday’s embrace of Mom. We stopped to see her on the way to Boulder, and I had to talk my way in, because it was the first day they tried to enforce visitor restrictions. I stroked her shoulders as she sat on her bed in the memory-care unit of the assisted-living home. I inhaled her smell and studied her body in case I never get that close again. Her caregivers eyed me suspiciously, as if I might bring in germs no matter how much I scrub my hands and cover my face. “I just hope we stay healthy to take care of them,” one said in a low voice to me.

The fact that my races are getting canceled barely registers, except I feel some relief. March through May, I was supposed to travel to Moab, then Sonoma, then Boston, then Hawaii for ultras and the marathon. Now training is one less thing to worry about. I need to run for health, not sport.

On a flat stretch, I do a set of strides while repeating the mantra, I am healthy, I am strong. I read somewhere that to cope with anxiety, it helps to repeat positive affirmations, so I say those phrases and try not to think, I can’t get sick, we can’t afford this.

If so much can change in a mere two weeks—from when our routines were normal and the economy hummed along, to social distancing and shuttered restaurants—then how unrecognizable would the world be in 14 more days? Our little corner of Colorado will be OK, right?

I can’t imagine as I run that exactly two weeks from now, my 53-year-old husband Morgan—my best friend since high school, my everything—would be lying in a hospital room, the eighth person in our county to test positive for COVID-19.

Morgan would see his oxygen saturation level dip dangerously as viral pneumonia attacks his lungs, and he’d wonder if he was about to enter critical care for a ventilator. He would ask himself, “Is this where it ends?”

And I would be at home with my kids, weeping when I catch sight of his jacket and hat on the coat rack. I would wonder if he’ll live to come back and wear them again.

***

On the drive home from Boulder, our son Kyle keeps asking to turn on the air conditioner. “It’s so hot in here,” he says, except it isn’t. I’m wearing winter clothes, and the temperature feels fine to me.

The next day, Kyle mostly stays in bed sleeping, coughing and developing congestion. Part of me worries it could be the virus. A few people have tested positive in Boulder, including a worker in their cafeteria. But I tend to believe him when he says, “It’s just a cold. I’m fine.”

I drive to the airport to fetch our daughter Colly, who is exhausted from packing and traveling. A day later, her long-term boyfriend, J.J., moves in with us from California for an indefinite period. Welcoming him feels like the right thing to do, because he makes our daughter happier and he’s almost like family. But we keep his presence secret, because soon after he arrives, the county decrees that all visitors have to return home.

We collectively commit to quarantine. I go from empty-nester to cook-and-housecleaner-in-chief for three young adults, relishing the sense of purpose and distraction from the news.

Kyle feels good again after a few days, and this unexpectedly pleasant week feels like a stay-cation. The boys play chess while my daughter makes funny TikTok videos. I run on remote dirt roads. Morgan channels the stress from his business into building a chicken coop, and we all play with the baby chickens that we keep in a box inside the house.

Morgan, J.J. and Kyle working on the chicken coop a few days before Morgan got too sick to get out of bed.

Then, about five days after the trip to Boulder, Morgan starts coughing. That weekend, Colly and I develop a dry cough, too. Thank goodness, J.J. never shows any sign of illness.

I meet someone to run on the third Sunday of the month. We park far apart from each other, and I shout through the car window, “I might be getting sick, and my son’s been sick, so keep your distance!”

We run a double-wide path through mud and slushy snow, always at least 6 feet apart, but it doesn’t feel right, as much as I enjoy her company. I decide to run alone from now on, because what if I’m contagious? Plus, I don’t want to feel pressure to keep up with anyone. I’m so tired, I mostly want to hike.

I feel a little hot and light-headed when I return home, so I take my temperature. In the high altitude where we live, 97.6 is normal. I’m a little over 99. A sense of dread returns to my stomach.

Colly wanders downstairs looking extra pale and sweaty. “Not great,” she answers when asked how she’s feeling. Her temperature is around 99. I wipe the thermometer with alcohol and get Morgan to take his temperature. He has a low fever too.

“Well, this could be the best thing ever!” he says, and it’s hard to tell if he’s serious or joking. “We’ll all have a mild case and then be immune.” We don’t bother going to the local medical center, because hardly any coronavirus tests are available, and they’re reserved for serious cases.

I allow myself a rest day and run five miles the next, hiking every uphill because my muscles feel extra weak. But I can breathe deeply, and I’m confident my lungs are strong.

I don’t get sick, I tell myself. Movement is medicine.

By Wednesday afternoon, my daughter and I feel close to normal again, but Morgan is worsening. I find him outside on a stepladder, trying to hammer the roof on the almost-finished chicken coop before the next storm hits. His eyes look sunken and his skin is flushed. He admits he needs a nap.

He’s been taking three-hour naps recently. Not only is he profoundly tired and mildly feverish, but he also has severe muscle aches around his trunk. His skin feels sensitive to the touch. He says he feels like he has a combination of mononucleosis and shingles.

He gets in daily contact with the Telluride Medical Center, a small facility with only a handful of doctors and nurses. The doctor over the phone concludes Morgan is not in respiratory distress. He can breathe well and hold his breath for 10+ seconds without coughing. Self-care at home is the best and only option.

For the next three days, Morgan stays in bed while drifting in and out of sleep. During this time, I email a running friend, “I’ve been up since 2:30 a.m. with anxiety—I literally have wondered if he’s starting the process of dying because he can’t get out of bed and feels so bad, but then I remind myself he’s breathing fine and his temp is only about a degree above normal.”

On Saturday at bedtime, I lay down next to Morgan. I refuse to leave his side to distance myself from his germs because I want to count his breaths per minute and monitor his cough.

Almost every one of his exhalations has become a mini-cough. His breathing is rapid, 38 to 40 breaths a minute, double or triple normal. When I turn on the bedside light, his skin looks grayish.

“Talk to me,” I say.

“OK. Need shower.” Driven by a desire to reduce the aches and cool off, he stumbles into the bathroom and manages a quick shower. I help him back to bed and take his temperature.

His fever has spiked to 103. “We need to go to the hospital now,” I say calmly.

“Tomorrow,” he mumbles. But I know we can’t wait.

I call the after-hours doctor at the med center and tell him my husband needs a chest scan and is having trouble breathing. He and a nurse prepare for our arrival.

Somehow, around 1 a.m., I get Morgan into the car—he moves in slow motion, he looks as if he has aged 20 years—and I drive the six miles to town, at one point swerving to avoid an elk. Morgan doesn’t notice the elk herd lining the road because he’s barely conscious.

Town is dark and feels deserted. The lone doctor and nurse meet us in the ER’s doorway wearing haz-mat suits. We put a mask on Morgan and guide him inside by his elbows.

The nurse immediately puts an oxygen-saturation monitor on his finger and sees a reading of 74 percent, indicating severe hypoxia. She puts a cannula in his nostrils so supplemental oxygen can flow to his system. Within minutes, his level rises above 90, out of the danger zone, and the nurse looks relieved. Morgan opens his eyes and says, “Oh my God, that feels so much better.”

Morgan in Telluride Med Center’s ER.

The nurse gives him a regular flu test, which is negative, then administers the COVID swab test. It will take five days to get the result back confirming he’s positive.

The doctor calls a radiologist to come in around 2 a.m. for a chest CT scan. They waste no time sharing the news: “We see bilateral viral pneumonia with the patchy pattern characteristic of COVID.”

Morgan looks brave, so I try to look brave too. But we both know there’s no treatment, only management, of this horribly stealthy virus. He had bacterial pneumonia five years ago, with wheezy fluid-filled lungs and chest pressure, but this type of pneumonia did not present any of those telltale signs.

Morgan will need round-the-clock care and potentially a ventilator, so I prepare to drive him an hour and twenty minutes to the nearest hospital in Montrose. We stop by our house on the way to pack some things and tell the kids.

I enter their bedrooms around 3:30 a.m. and say, “Get dressed and come down, your dad needs to talk.” They instantly sense the seriousness and hurry down.

Sitting on the bench in our entranceway, a portable oxygen tank attached to his nose with thin tubes, Morgan rallies to explain his diagnosis to the kids in a reassuring voice. “The good news is,” he says—because he always tries to stay positive—“the hospital is not crowded, and if I need a ventilator, they’ve got one.”

Colly and Kyle stand blinking in the light, telling him he’ll be OK and promising to take care of the animals. They take turns hugging him and saying they love him.

I know this may be the last time they see their father for days—forever?—so there is no way I’m going to tell them to refrain from hugging because of his contagion, but I do remind them to wash their hands.

I pack a small bag for myself, intending to stay at the hospital. Only when we arrive at the parking lot does it hit me that I have to drop Morgan off and leave. A security guard is apologizing but insisting that I can’t enter if I might be contagious.

I get in the back seat where Morgan sits with the oxygen tank. I’m all business—“you got your phone, your charger? I put a book in your bag that I think you’ll like”—and then I feel my face crumple and can’t even say goodbye. I hold his shoulders to pull him closer, and he hugs me back.

“Call me, text me, promise,” I say.

“I will.” He gets out with the help of a nurse in protective gear.

I pull myself together to drive home. The route skirts the snow-covered 14’er Sneffels, and as I look at that craggy peak glowing at sunrise, I imagine how my grandpa’s brother, Dwight Lavender, must have looked when he did so much mountaineering on those slopes as a young man in the early 1930s. He was a famous climber until he caught the polio virus and died in less than 72 hours at age 23. If it happened to him, it can happen to Morgan. No matter how strong we are, we are vulnerable without vaccines and other medicine.

My mind spins into scenarios of life without my husband. I want to celebrate our 30th anniversary this June, I want him at our kids’ weddings if they get married.

Being an ultrarunner doesn’t exactly prepare me for a moment like this, except that the phrase I repeated during the most fatiguing moments my last self-supported stage race comes back to me: Get through it. Quitting is not an option.

When I get home, I’m relieved Morgan answers my call and can talk. He says the doctor put him on two types of antibiotics and told him, “We’ll know soon enough if these are any help.” Either he’ll stabilize, or he’ll enter critical care. (Antibiotics don’t fight the virus itself, but many doctors prescribe them for the coronavirus to fight any secondary infection and to try to reduce lung inflammation.)

I try to catch up on sleep, but I can’t. So I get dressed and go for a run, but I can’t. My legs feel like they might give out. I hike to the half-mile point up the road and turn back, walking slowly and using this time to cry out of sight of others.

I have trouble sleeping that night and long for the sound of Morgan’s breathing. When I call the hospital in the morning, a nurse informs me she had to increase his oxygen to get his saturation level back up. I interpret the chilling news as a sign his lungs are giving out.

When I get through to talk to Morgan, he says, “I thought that was it, that I’m going down” when he couldn’t get enough oxygen, “so I really tried to think through what was going on.” He realized his nose felt extra stuffy, so he asked a nurse to flush out his nostrils with saline drops, and then he could breathe better.

“I’m hoping my problem is just boogers,” he says, and we both laugh a little.

“You know,” I say, “if you have to go to the ICU, then you’ll need to decide whether you want to stay there. Because you’ll be alone at the end and sedated, but I could come get you and bring you home.” My voice breaks. “I think it would be better to have you here with us if you’re not getting better, so you need to talk to your doctor about this while you can.”

“I know,” he says, “I thought of that.”

***

Morgan doesn’t need intensive care. After about 36 hours, I get a call telling me he can recover at home.

I’m slightly disbelieving. It feels like we won a coin toss: Morgan gets to come home, others stay in the hospital and die alone. But I’m flooded with relief as I speed through the long drive back to get him.

He’ll need to be hooked up to oxygen for many days, maybe weeks. He’ll get drenched with night sweats and suffer more headaches. His diminished sense of smell and taste will be slow to return. Time will tell if he’ll get well enough to enjoy high-altitude hikes this summer. But we are together, and each day he seems a little more like himself.

Morgan resting back home, saying hello to the baby chicks Tik and Tok and our dog Beso.

I wait five days to try running again, and when I do, I’m nervous. Running might make me feel sick and weak. I’ve lost faith in repeating, “I am healthy, I am strong.” I still fear the virus in us.

I commit to go slowly and limit myself to three miles. My legs feel better from all the rest. I notice how much the snow has melted in just a week, because we’re into April. A virus can’t stop the seasons.

I suddenly need to hear the passage from Ecclesiastes, for the reminder that humans always get through dark times, so I play The Byrds’ Turn, Turn on my phone as I run.

A time to kill, a time to heal. A time to laugh, a time to weep.

I have to walk for a bit as the music continues so that I can process one last cleansing cry, and as I do, I mentally add these phrases to the song: A time to rest, a time to run.

My comeback run.

Some questions that readers may have & some answers

What about the antibody test being done in Telluride—did you get that done?

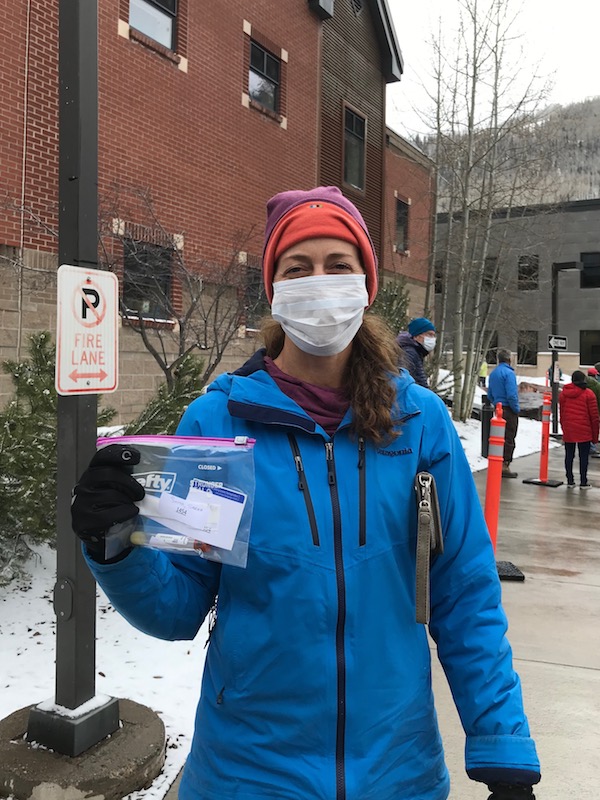

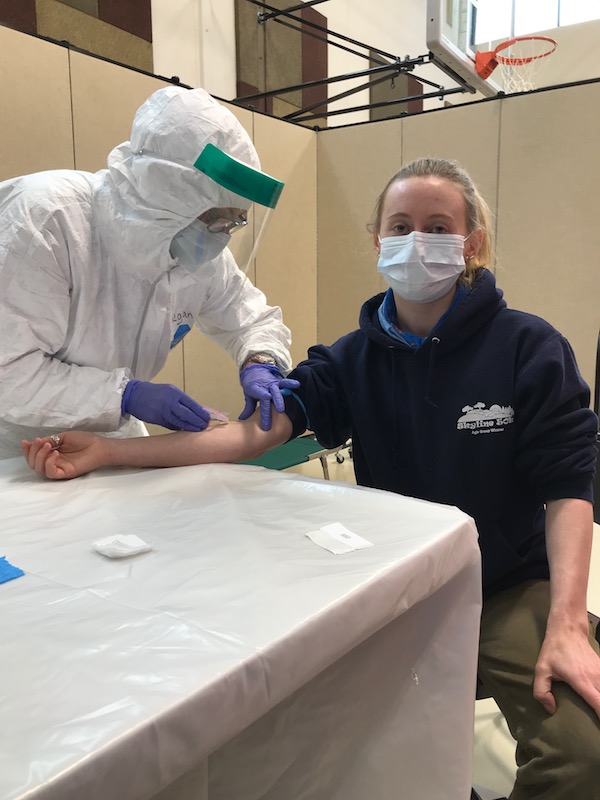

Yes, we are so fortunate to live in a county conducting this test for all residents who want it. It’s all thanks to a couple who live here part time and head up a biotech company that developed the test; see this article for info. It was amazing how an army of local volunteers and health-care workers mobilized to methodically test us all. The kids and I went in for testing on Thursday, March 26, about 10 days after Kyle developed symptoms and a little less than a week after Colly and I started feeling ill. Morgan did not get it done because he felt too weak to go to town. We got our results back a few days ago, and we were a little disappointed they’re all negative, because we wanted to see that our bodies had antibodies that hopefully will protect us from re-infection. But, it may be a false negative, as it takes about 14 days from exposure for the body to develop antibodies. We will get a follow-up test done at the two-week period. [UPDATE: The follow-up testing never happened, unfortunately, due to the crisis in New York delaying results and limiting their usefulness; see article for details.] Overall, the first round of test results showed about 97% of the county residents tested negative, 2% inconclusive, 1% positive. Here are a couple of photos of me and Colly getting tested; everyone got handed a mask to wear and a baggie with blood-draw materials, and then the volunteer health care workers wore full protective gear.

Did you self-isolate in your household?

“Self-isolating” means separating a sick person from others living with that person. A lot of coronavirus patients are extra good and careful about staying in a separate room and not interacting with others in the household at all. The answer is, no, we blew that; by the time we realized that we probably had the virus, and then Morgan got really sick, it felt like it was too late—the horse had already left that barn. We shared spaces, touched the same doorknobs, etc., but I redoubled my efforts to keep the house clean with disinfectant, and Morgan ate meals far apart from the rest of us (when he wasn’t in bed, which was most of the time). I felt I had to keep sleeping next to Morgan to monitor his condition, and who knows? Maybe this saved him; he could have slipped into unconsciousness when suffering high fever and hypoxia, and we would have delayed getting him to the med center, if I wasn’t at his side.

We did, as a household, redouble our efforts to quarantine and stay far away from others. Before I realized we were likely COVID-positive, I had been going to the post office and grocery store a few times, and those times I always wore a mask, gloves, and I used a disposable wipe to touch common surfaces like door handles. When we realized how sick Morgan was, we started asking friends to do our shopping for us, and they’d drop our items off in our driveway. The county health person who has been monitoring our household (and who knows the full story of our conditions and the fact my daughter’s boyfriend also is living with us) just yesterday gave the green light for me to do essential outings, given the timeline of our symptoms. I promise that when I go into a store, I will still practice social distancing and be extra careful with mask, gloves, and using wipes to touch common surfaces.

Why do you think he got through this without worsening and needing a ventilator?

Someone posted a message to me on Facebook today with the best of intentions, saying divine intervention saved Morgan, and although I have faith in the holy spirit and I attend church, I do not believe in a God who is a micro-manager, because to believe it was prayer or divine intervention that saved Morgan implies that those tens of thousands who are dying didn’t deserve such divine intervention or the prayers didn’t work for them, and I don’t believe that at all. (Although I do, certainly, appreciate everyone’s prayers as a mental commitment of care and good will that helps on some level, as it communicates love.) Rather, I believe a combo of luck, science and action saved him. We are so lucky to have access to an uncrowded medical center in Telluride with attentive doctors and nurses, and that the facility had a CT scan machine. And then, we were lucky to have a regional hospital with attentive and not-yet-overwhelmed caregivers. We also are fortunate that the two things he needed as a lifeline to return home—an oxygen saturation/pulse monitor, and in-home oxygen equipment—were available. Only four oxygen saturation monitors were left in stock at the pharmacy, and we got one. The oxygen rental place that delivers to our home also is getting stretched thin. I think—but we can’t really know for sure—that the antibiotics helped his body heal in some way, or at least gave his body the best fighting chance. And I think it was just good timing that we recognized the pneumonia early enough, and started him on the oxygen flow, so it prevented the horrible viral infection in his lungs from spreading and shutting down his ability to process oxygen at all.

How is Morgan doing now, one week after his hospital release?

Better! He still needs supplemental O; when he takes it off and moves around, his O saturation level drops to the low or mid 80s, so his lungs need more time to heal. But he no longer has night sweats or headaches; his appetite is back, along with his sense of smell and taste. The mental fog lifted, and he was able to spend the better part of the weekend at his computer dealing with the application for an SBA business loan for his company. Unfortunately, his eyesight noticeably worsened during his 10 days of illness, so he still can’t read as well or focus well on a computer screen. Today he felt well enough to move around outside and put the finishing touches on the chicken coop, wearing a portable oxygen tank in a backpack. He intends to get follow-up testing as soon as he can; he hopes to discover that the regular COVID test would be negative, and the antibody test would be positive.

UPDATE: Both Morgan and I got second COVID tests (the regular kind, not the antibody test) on April 21, and they came back negative, confirming we no longer carry the virus and are no longer contagious. Morgan also got an antibody test that came back positive. He stopped using oxygen supplementation during the final days of April, so basically, it took him a full month from his hospitalization to recover.

Morgan in the horse paddock putting primer on the chicken coop, wearing portable oxygen and happy to be outside—happy to be alive.

Why did you build such a massive chicken coop for only two baby chicks?

Good question! We actually have ordered eight baby chickens from a mail-order service, which are supposed to arrive April 13, but given the delays in shipping and the shutdowns in business, who knows if they’ll arrive? We bought the two little chicks from a local ranch-supply store when we knew the kids were coming home from college, as a fun addition to the family and to practice taking care of the eight that supposedly will hatch and be shipped next week.

How are the rest of you feeling?

Good! I’m still a little scared about the possibility of re-infection, and I have been nervous all along that J.J. might get sick too. But I think we’re all going to be OK. I felt a little stronger on my run today. We will continue to be vigilant about hand-washing, mask-wearing and social-distancing.

Are you still coaching?

(planted question for shameless self-promotion) Why yes, I am, thanks for asking ;-). Several of my clients went on hiatus, partly because their goal races got canceled and partly for financial reasons, so I have openings available. Now is a great time for remote coaching—and for all the inspiration, motivation and accountability that comes with it! Check out my site and contact me if you’re interested. Or if you want to self-train with guidance, I encourage you to order my book, The Trail Runner’s Companion.

Thank You

I am overwhelmed by all the support we received from emails, text and via social media. I can’t adequately thank our community of friends (here in Telluride, back in the East Bay, from Thacher School and elsewhere) enough for all their concern and offers of help. I also have profound appreciation and respect for the doctors and nurses who cared for Morgan at Telluride Medical Center and Montrose Memorial Hospital. It was so odd and frightening to realize we have “the plague” and could spread it further and hurt more people—I’ve felt some guilt and shame mixed in with all the other emotions. Thankfully everyone has been so supportive. I hope by sharing our story it helps put a face on the growing number of seriously ill and dying coronavirus patients. If you want to read a moving first-person story about what this virus does to the body and how it affects patients and their caregivers, without a happy ending, I encourage you to read this doctor’s account published in the Washington Post.

Fellow trail runners, I encourage you to follow and support iRunFar’s #OperationInspiration and join the community donating to the WHO’s COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund.

What a moving post! I, too, have been thinking of Dwight, and of Grandpa who, during all those walks he and I and baby Bren took while he regaled me with stories from his youth, never mentioned the Spanish Flu (which devastated Telluride–did you see the Daily Planet article?) and which he must have lived through as a young boy.

We are so appreciative of being able to shelter in place in your glamping tent, and love seeing Morgan down below in the paddock, on the mend with his portable O2 tank and finishing up his vision for the chicken coop.

Looking forward to the day when we can narrow this distance,

-D

The thing I appreciate most about your blogging has been the human aspect of competitive running — not miles or speeds, but how you feel, what it’s like, how you emotionally support yourself. Reading about your fears and positive actions taken with and on behalf of your family is very encouraging. Thanks very much for sharing your experiences. I hope things continue to improve for you, Telluride, and the rest of the world.

Thanks for the testimony of how vigilant you have to be in order to keep a loved one protected and cared for during these incredibly difficult times.